Excerpt: “Humanising” stories blunt our consciousness about how violence and death come about.

I live in Chicago, which means that I wake up every day to local newspaper accounts of shootings, murders, and violence. That’s not necessarily because we are inherently a greatly violent city but because Chicago news outlets have bought into the idea that writing, a lot, about death here is what will keep them afloat, and national papers like the New York Times mostly pay attention to Chicago when they can focus on the topic of guns and violence.

But I digress. My point today is not that we should focus more on “good stories”: Chicago is a massively, beautifully, horrifically, excitingly, maddeningly complex and complicated city, and the range of work we could produce about it far exceeds the pitiful frames in which others (and too many of our own writers) choose to place us.

Rather, I want to point to one aspect of all the reportage around death and murders that’s present not only in accounts of such in Chicago but everywhere else: the constant need to hunt for back stories of victims that show how kind, how good, how exceptional they were. I won’t point to specific reports, to avoid causing further pain to friends and families of the dead but I think you, as readers, know exactly what I mean. Nearly every death from a shooting or murder is recounted as “Murder Victim Was an Exceptional Father and Friend” or “Woman Brutally Killed in X Only Wanted A Better Life,” and so on.

Are such deaths, wholly unexpected and often violent and brutal, to be mourned? Yes, absolutely. But why should we need stories about how good and loving and kind and decent these people were, to mourn their deaths?

We should seek to end all violent and unexpected deaths, not just those of people we’re compelled to like. When journalists and writers set about looking for the back story of a victim, they do so because they know perfectly well that no one is interested in, say, the life and sudden death of The Creepy Guy in the neighbourhood or the woman who may have sustained herself by Dubious Means or the teen who was clearly too addled to make much sense and was probably Knifed by a Client in an alley or the Bad Mother whose kids may have often been heard crying.

Reading stories about the goodness of a victim makes us feel good about ourselves, and it prevents us from thinking more systemically and thoroughly about how violent and unexpected death comes about. It encourages us to ignore the deaths of people we can’t bring ourselves to like and thus ignore how our systems are failing those who end up in circumstances where they meet such ends. Reporters and writers are always told to “humanise” victims, but we need to think about death and violence and brutality as the effects of a society that fosters conditions of violence and brutality—and for that to happen, we have to think more abstractly about how death, many kinds of death, comes about.

If we actually feel compelled to “humanise” people who are killed, that’s not a sign of our goodness and humanity: it’s only a sign of how utterly heartless and depraved we are. Death and violence are awful, no matter who suffers from them. “Humanising” stories blunt our consciousness about how violence and death come about.

I’m really so, so tired of us, as humans, honestly. So sick and tired of our constant need to only show compassion to those we can like, and pretending that this is somehow indicative of our “humanity,” whatever that is.

If you’re a journalist or writer interested in these deaths, stop looking for such back stories. As readers, push back. Demand more, demand better, demand that we start looking closely at systems, not just the lives of the good people crushed by them.

***

Here are links to other pieces where I address these issues:

“The Politics of Storytelling.”

“On Death and Exceptionalism.”

“Hate Crimes, Exceptionalism, and the State’s Order to Kill.”

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

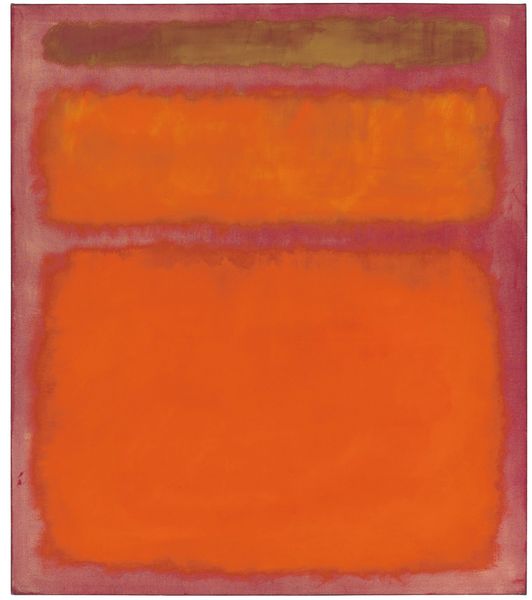

Image: Mark Rothko, “Orange, Red, Yellow,” 1961.