Note: This is the main essay in an ongoing series on plagiarism, a topic I’ve written about for a long while. For a full list of the rest of the essays, including those that are forthcoming, see “The Plagiarism Papers.” You may not agree with every one of of my points here, but you have to pay attention — there is an epidemic of plagiarism. The stories I present here are cobbled together from different accounts and sources are anonymous, in order to protect the privacy of people concerned. So if you are among those who plagiarised the work of your underlings, and think that something I wrote here is an exact account of what you did because the details match what you did: please don’t go searching for your victims to take revenge upon them. The sad truth is that such acts of exploitation are, as I write below, depressingly familiar and eerily similar. Like mushrooms after the rain, plagiarists are everywhere.

I. Water

David Foster Wallace began his Kenyon College graduation speech with this anecdote: two young fish are swimming in the ocean, side by side. An older fish comes upon them and asks, “Morning, boys! How’s the water?” The younger fish swim on for a while and then one of them turns to the other and asks, “What the hell is water?”

As Wallace explained, the point of the fable is that “the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.”

I thought of this story often as the Claudine Gay fracas unfolded across headlines for weeks, turning from a matter of alleged anti-semitism to alleged plagiarism faster than an Elon Musk rocket exploding after its launch. There was and still is a great deal of noticeable pearl-clutching on all sides, and several commentators were and are eager to point out they would, of course, never plagiarise and would be ever so shocked to see any evidence of intellectual theft among their colleagues.

But plagiarism is very much the large body of water in which the world of publishing swims along or, rather, floats as a gilded turd, oblivious to its turd-ness and deeply self-assured about its glitter.

Plagiarism is rife across all genres of writing, from the academic sort in which Claudine Gay first made her name as a scholar or the non-academic kind, like the January 3 op-ed she penned for the New York Times, a day after she had (effectively) been pressured to resign from her position as Harvard’s first Black president (and only the second woman to hold the post). The surprise is not that Claudine Gay should have plagiarised parts of her work, including her dissertation acknowledgements, but that everyone is so surprised: plagiarism in publishing is not some startling anomaly but the very nature of the beast.

The Gay scandal has exposed the extent to which plagiarism runs unchecked and is even encouraged in many quarters, especially at elite institutions. But it has also distracted our attention from the fact that plagiarism is not simply a problem of people failing to use quotation marks or cite their colleagues: it is about the extraction of material resources and the exploitation of labour.

Plagiarism can be the kind that Gay engaged in: wanton and clear, it involves the copying of entire passages and sentences from unattributed sources, and is easy to detect once it’s found out. It can also be a form of unseen theft — what I call “soft plagiarism” and, borrowing from anthropologists like Margot Weiss and climate journalists like Amy Westervelt, “extractive plagiarism.” These latter kinds of plagiarism occur when a critic at a popular magazine filches the work of a lesser known writer and presents the analysis as her own, when an established professor listens attentively to a graduate student’s striking new theory at a conference and then writes it all up as an original and “groundbreaking” piece of research in a prestigious journal, or when a major media outlet presents the work done by a smaller one as its own “scoop.” As Christopher Sprigman points out, rules against plagiarism exist to “protect readers’ interest in not being defrauded.” Whether or not two writers have really made substantially unique contributions to the discourse on a topic should be left up to an informed reader to judge. Unscrupulous writers, however, steal and repurpose the work and ideas of others by not letting readers know where they originate and by presenting them as wholly original.

Claudine Gay’s plagiarism, perpetrated by the former president of one the world’s most highly regarded universities, has created the impression that this is a unique Harvard problem with just an individual. In general, the response has been of shock, as if people were asking, “Oh, no! How could this happen at Harvard?” Instead, we should assert that it happened precisely because Harvard is set up to enable the kind of resource and labour exploitation that plagiarism represents, and that it has set the standard, such as it is, for other institutions. The furore over Gay erases a critical point about plagiarism that has not been considered so far: that it is connected to the accrual and withholding of actual, economic resources.

Plagiarism, whether in the supposed upper echelons of academia, in high schools, newspapers and magazines, or in Substack blogs, is tied to the accumulation of influence and a measure of discursive power: future publications in journals or magazines, a place in a profitable lecture circuit, the ability to become an “expert” rendering pronouncements on political and cultural affairs, appointments at universities or think tanks, and much more. A plagiarised idea or article can mean the difference between a sustainable writing career and an unsustainable one for the person whose work is stolen. It is a structural problem tied to the plunder of resources that marks the contemporary publishing world. Here, ideas, analyses, and approaches to objects of study are the raw material upon which entire fields of study and journalism depend.1Certainly, two people might think of very similar approaches or have very similar notions — what is the world if not a vast reservoir of thought? — but they will still bring unique perspectives to their subject. For more, see my “On Originality.”

Plagiarism is embedded in actual, real resources. At universities, scholarly prestige may not translate to much money (especially as salaries at most institutions rapidly stagnate or dwindle) but a job at an institution can mean healthcare and benefits and also literally invaluable access to the resources that such places zealously guard as their own — including priceless historical documents, rare books, and expensive journals (some so costly that even Harvard cannot afford them), never available to the general public.2(Added Feb. 16) For more on the neoliberal university and its plunder of cities, see Davarian Baldwin’s In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower.

These crucial facts — that plagiarism is commonplace in publishing, that it takes many different forms beyond insufficient citation, and that it is fundamentally about economic power, not moral failings or inadequate acknowledgements — have so far been ignored in the discussions about the subject. Many writers and academics (and their editors and publishers) don’t want to admit that their profession is deeply corrupt and that they often enable that corruption. And academics and writers don’t simply steal from each other: they teach upcoming generations that plagiarism is acceptable as long as the material they steal is from more vulnerable people who cannot fight back and as long as they don’t get caught. Harvard, for instance, is strict about plagiarism but only with its students: as the Harvard Crimson points out, students who plagiarise can, by the book, be prevented from getting their degrees, whereas Gay’s plagiarism is not even named as such. In media, the New York Times is especially notorious, as we will see, for poaching the work of smaller newspapers whose reporters, often freelancers, spend months researching and reporting stories only to see the Grey Lady stride in imperiously and re-present scoops as its own. Hypocrisy rules at the paper which, in December of 2023, sued “the creators of ChatGPT and other popular A.I. platforms, over copyright issues associated with its written works [and] …contends that millions of articles published by The Times were used to train automated chatbots that now compete with the news outlet as a source of reliable information.” In effect, the Times is angry that its articles are being harvested by ChatGPT, while it does something remarkably similar to smaller, less powerful publications who must also “compete with the news outlet as a source of reliable information.”

As to that water: like real oceans, it’s everywhere, all around the world. Germany, for instance, appears to have an epidemic of plagiarism (or at least a desire to root out PhDs who may have produced shoddy doctoral work). Harvard seems to have a particular problem: faculty like Jill Abramson, Alan Dershowitz, Lawrence Tribe, and Charles Ogletree have all been charged with plagiarism. Of the four, only Dershowitz has been cleared by Harvard (although the matter remains a topic of debate). None of them have suffered sanctions and all are still affiliated with the university. Harvard, where Gay received her PhD in 1998, has also seen very public cases of its own students and graduates being exposed for their plagiarism. In 2006, the Crimson broke the story that Kaavya Vishwanathan, then a sophomore at the university, had plagiarised her Young Adult novel How Opal Mehta Got Kissed, Got Wild, and Got a Life from fellow YA author Megan McCafferty, Salman Rushdie (yes, that Salman Rushdie) and others. Doris Kearns Goodwin (who, like Gay, earned her PhD in Government from Harvard) was accused of plagiarism in 2002: she revealed that she had been accused of the same as far back as 1987 (her publisher Simon & Schuster settled with at least one author).3For more on Doris Kearns Goodwin, see my forthcoming, “Plagiarism Has Its Rewards.” Judging by the vast number of stories on the topic that appear in publications like The Chronicle of Higher Education or Inside Higher Ed, all of the above represents only a small sample of cases of academic plagiarism. In this context, it is quite unsurprising that one of Gay’s fiercest critics, the billionaire Bill Ackman, immediately saw his wife accused of plagiarism too. It’s plagiarism all the way down.

The discourse on plagiarism has so far yielded few real insights and is mostly empty and repetitive, making obvious points that enable several hundred clickbaity pieces that say the same thing by taking either one of two sides. And questions about what to do only revolve around surveillance, detection, and punishment. But plagiarism is both a metaphor and a practice: it describes the current state of publishing as a place of perpetual pillage as well as the acts of filching and theft that define it.

And it takes many forms.

II. The Shape of Water: Plagiarism in Its Many Forms

In all the din over Gay, most commentators have neglected to emphasise two key points about plagiarism. The first is that what makes plagiarism unacceptable is not that it might be caught and punished, but that it is inherently wrong. To use an analogy: the problem with murder is not that one might be found out and imprisoned or worse, but that one should never take the life of another.

The second point is that plagiarism is not a matter of scale, and there is no such thing as minor or harmless plagiarism: a student who plagiarises the notes and words of their study group partner is as much a plagiarist as the president of Harvard who lifts entire paragraphs (and even acknowledgements) from other scholars. In one of the clearest examples of Gay’s plagiarism, she duplicates language found in a 1996 paper by Bradley Palmquist and D. Stephen Voss in her 1997 dissertation, and fails to mention them anywhere. In his response to various media outlets, Voss has repeatedly said that while what Gay did was “technically” plagiarism, he considered it “minor-to-inconsequential.”

Yes, well: the ashes of my two dead cats sitting atop my desk signify that they are technically dead. The widening girth and painful ankles of a woman who is about to deliver twins any day now mean that she is technically pregnant. “Technically” carries a heavy burden here, of having to pretend to be the difference between plagiarism and not-plagiarism. But as Michael Dougherty, a professor of philosophy at Ohio Dominican University, has pointed out, the responses of those plagiarised are not the point: “I think the feelings of the true authors are largely irrelevant…[t]he way I approach it is [to] focus on the text, not on the feelings of those whose work was stolen.”

Voss and others like him seem to think that some of what Gay did was too small to note, like the difference between petty shoplifting and driving a tank through a bank’s vault door. But plagiarism is plagiarism, even when unintentional (in Gay’s case, there are too many instances to qualify her as an unintentional plagiarist). If the rules don’t apply to everyone, why have them in the first place? 4For more on Claudine Gay, Voss, and race, see my forthcoming “Race and Claudine Gay.”

Scan the internet for academic rules on plagiarism, and the search yields as many policy statements as there are institutions. Most of them focus on detection, surveillance, and consequences, but plagiarism is about much more than following rules in order to avoid being caught. To cite and name the work of others is to be part of a larger community of people, to acknowledge that while one might certainly have original insights, those are born within the wellspring of intellectual work done by many before and alongside the writer.

To that end, Oxford University’s definition of plagiarism is a far more useful and even a very poignant reminder of why plagiarism matters. Founded in 1096, the world’s second-oldest continuously operating university has had time to reflect on these weighty matters and its statement on the issue is one of the longest, most detailed, and most reflective to be found anywhere. It does not simply define plagiarism but explains what it means in the context of inhabiting the world as an intellectual, a scholar, a thinker, and a writer.

The statement begins in a straightforward fashion by defining plagiarism as: “Presenting work or ideas from another source as your own, with or without consent of the original author, by incorporating it into your work without full acknowledgement.”

Then, in a section titled, “Why Should You Avoid Plagiarism?” it lays out what the stakes are:

You are not necessarily expected to become an original thinker, but you are expected to be an independent one – by learning to assess critically the work of others, weigh up differing arguments and draw your own conclusions.

This is an extraordinary statement that runs counter to the fetishisation of originality that is so rampant in publishing. Both academic research, across disciplines, and mainstream publishing rely on the idea that all ideas are singular in origin and value. The myth of the “Eureka!” moment is pervasive in popular representations, embodied by the caricature of the lab-coated (and of course male) scientist who spends hours peering through a microscope until his genius and brilliance yields results (while his female assistant flutters in the background, bringing him endless cups of coffee). In the humanities and social sciences, the central figure is more likely to be the brave researcher who spends years cohabiting with an entire community and unravelling its ancient wisdom or the Shakespeare scholar who discovers a hitherto undiscovered sonnet. The publishing world separates originality from independent thought, but Oxford positions them in relation to each other, as interdependent concepts: it suggests that no scholarship is outside “the work of others” and it persuades students to “weigh up differing arguments and draw your own conclusions.”

It goes on:

It is important to appreciate that mastery of the techniques of academic writing is not merely a practical skill, but one that lends both credibility and authority to your work, and demonstrates your commitment to the principle of intellectual honesty in scholarship.

Oxford’s statement on plagiarism is an excellent guide for scholars at all levels. But as the lines between academic and non-academic writers blur, as universities and publications disappear or conform to the pressures of the market, more writers chase publishing opportunities at the expense of adhering to such principles. Increasingly, journalists look for semi-secure appointments at universities, while academics look for assignments in online and print magazines. The era of the talking head academic, brought on to make some quick but learned comment during a newshour, is over. Academics are now part of the DNA of everyday discourse, as Judith Butler expounds on Israel in the pages of The London Review of Books and The Boston Review (with disastrous consequences when her liberal Zionism stands exposed, but that’s a matter for another essay). Academics now find themselves pitching to editors, who are in turn delighted with this new pool of writers that offers free or cheap labour.5For more on academics scabbing at non-academic venues, see my work.

The problem here is not an “overproduction of PhDs,” a favourite catch-all phrase in academia often used to explain away the shrinking job market. I agree with Kevin Drum that the real problem is that the number of tenure-track positions has been drastically eroded. Along with that comes a relentless push on the part of the neoliberal university to decrease costs by replacing full-time tenure-track lines with cheaper adjunct labour. The New York Times Company has a formidable number of employees (counting non-journalists) and the paper does do a lot of actual reporting, even with its patterns of theft. But for a reader perusing the website, the Times is less a newspaper and more of an aggregation of … stuff, and most of it reads like it was written by a bot, even if it is not. Trying to find contemporaneous, actual news on the Times website is like trying to catch bubbles in water: the page changes every minute, depending on what the algorithm decides is relevant, and that article you’d hoped to read will disappear while ten more on the Oscars take its place. There’s a newspaper buried in there somewhere. But, as with the PhD, there is no overproduction of writers. What we do have is the lack of a solid, reliable publishing world with publications, editors, and publishers who believe that their job is to create excellent reading material, not “content.”

In this context, it’s a winner-takes-all atmosphere, with writers (including academics, who like to think of themselves as above the fray) jostling each other for prime media real estate and vomiting out mindless pieces everywhere. How many opinions on Barbie can you fit on the head of a pin? Millions, it turns out (no, really, literally: google “Barbie snubs” and you’ll see what I mean).

In this fractured publishing landscape, what counts as a new perspective? Readers have contributed to the current morass with a voracious appetite for content, and demand massive quantities of it, like customers at a $10.99 buffet, dissatisfied that there are only four kinds of pasta when they want eight. As a result, writers are constantly trawling for new ideas — academics and journalists alike swim in the seas of social media, like giant whales swooping up krill. And despite what the Right wants to believe about the media and academia’s Left bent, the truth is that both worlds operate within strict hierarchies of power that would make members of the Vatican gape in awe (and take frantic notes). Writers and publishers have a particular disdain for lesser known writers and believe that material like that found on individual writers’ websites or in “lesser” publications are theirs for the taking, like books in a Little Free Library box.

In this swirl, plagiarism itself has taken on multiple forms. Broadly speaking, there are three kinds: Hard Plagiarism, Extractive Plagiarism, and Soft Plagiarism. While these are distinct types, they often merge into one another, creating hybrid forms.

Hard Plagiarism. This is what we might also call Classic Plagiarism, the sort that brought Gay into the limelight, and which seen clearly in Kavya Vishwanathan’s filching of entire passages from authors. This is the most obvious kind of theft: the deliberate taking of someone else’s words and thoughts and passing them off as your own.

Extractive Plagiarism. This is the kind most often perpetrated by large media outlets, or by unscrupulous and lazy reporters: when one writer goes so far as to rewrite a story originally written and researched by someone else, and re-present it as a scoop without mentioning the first writer. Extractivist plagiarism is a plundering of another’s work by going so far as to chase down their very same sources, and presenting a provocative thesis as one’s own. The climate journalist Amy Westervelt has been producing a significant body of work for over two decades, and it includes an award-winning podcast Drilled. In an unpublished essay, “Extractivism Has No Place in Climate Journalism,” (for which she also interviewed me about my own experiences), Westervelt describes how she and other climate researchers have regularly had their work plundered by larger media entities. For example, in 2022, the BBC journalist Jane McMullen presented what appeared to be a docuseries scoop, “about the moment the fossil fuel coalition joined forces with a PR genius to spread doubt & persuade the public that climate change was not a problem” which, she said, “happened at a little-known meeting, 30 years ago, in autumn 1992.” Explosive stuff, certainly.

Except: Westervelt had already covered this story in 2020, and even written about it for The Intercept, which meant that McMullen’s work was hardly a scoop — producers even told a source they approached that Westervelt was a consultant for the project, which persuaded the source to work with them . McMcullen could easily have begun by interviewing Westervelt, and the result would have been a more intellectually generous project, created in a collaborative spirit, expanding on Westervelt’s find. Certainly, the BBC has more resources and can literally go places where an independent journalist cannot, and it has a century’s worth of international networks and prestige to draw upon. Why not include Westervelt, rather than erase her critical work? Westervelt points out the irony of all this, given her field, and “the way that increasingly common extractive practices in journalism conflict with a key goal of climate journalism: to expose the ills of extractive practices and highlight the need to do things differently. How are you going to stop extractivism while being extractive?”

The New York Times is especially notorious for swooping in and presenting provocative stories as original reporting. A 2019 Vice article noted that the paper outright refuses to even hyperlink to stories when asked (and counter to the advice of its then public editor, Margaret Sullivan, whose position no longer exists). Its reporters and editors will aggressively refuse to acknowledge the work of those they steal from. In August of 2023, Norimitsu Onishi “reported” for the Times on the unusual story of two Canadian men who had been switched at birth to families of different ethnicities. The story had already been broken by Lindsay Jones of the Canadian Globe and Mail in February of 2023, and with much the same angle on issues of native and racial identity (Jones, as a Canadian writer, provides much more history of the Canadian government’s separation of children from their Indigenous families). To date, despite Jones publicly pointing out that she had broken the story, the Times has not acknowledged that it originated with her. This is par for the course for the paper — it very rarely inserts a note in an article about the origins of its reporting (and when it does offer an acknowledgement, it often does so via stealth editing — without noting the change, thus making it seem like it had been conscientious from the start). Jeff Jarvis, a writer and journalism professor, has written about its especially egregious coverage of Haiti and the way the NYT wrote about the “history of Haiti’s impoverishment at the hands of its overthrown colonial overlords” as if discovering and exposing it to the world for the first time. In fact, as many historians and other academics know too well, there has been a vast body of literature on the subject and many academic discussions for decades. Jarvis quotes American Studies professor Joseph Rezek, who explained why academics objected to the way the Times presented the story: “The hook for the article, that the NYT uncovered this about Haiti, is false; that is why people are mad. The narrative in the piece, about the debt, is good. The narrative of discovery is bad…”

“The narrative of discovery” is exactly what too many journalists and academics cling to, that Eureka! myth. Lindsay Jones spent months researching and talking to the people involved in her story, and the Times simply swanned in and used the same sources and analysis.

Soft Plagiarism. This is where hard plagiarism meets extraction, and involves far more guile and outright theft, but not the kind that’s easily discovered. Soft plagiarism occurs when one writer takes the kernel of another’s thesis and reformats it to look like their own or even simply claims it as an original thesis, usually aided by the fact that the work is either unpublished or the originator has published it in a “lesser” outlet.6I have been using this term for a number of years, with this very specific meaning. Only recently, sometime in the last few months, did it come to my attention that the term “soft plagiarism” was used in a 2002 dispute involving Australian historian Keith Windschuttle and the anthropologists Robert Manne. The latter accused the former of “soft plagiarism” by copying “chunks of someone else’s work without putting them in quote marks or footnoting them…” This is not how I use the term, and I would in fact call whatever it is that Windschuttle is supposed to have done Hard or Classical Plagiarism.. It happens unobtrusively, its effects are often unseen or, if witnessed, unremarked upon because of the unequal power plays on hand. An example: Following the revelations about Gay, Genevieve Guenther tweeted about her former professor, a world renowned Shakespeare scholar whom we shall henceforth refer to as “Shakespearewallah.” According to Guenther, she made an original argument in her presentation during one of his seminar classes in 1996. A week later, Shakespearewallah returned to the class with a version of a paper he was going to present at that year’s annual Shakespeare Association, “re-articulating exactly what I had said about the same material the week before,” as she puts it. Shakespearewallah could easily have included Guenther as a co-author or even cited her (thus greatly aiding a junior scholar), but deliberately chose not to in order to maintain his reputation as a brilliant and original thinker.

Such discussions of soft plagiarism are not uncommon in academia. Over the course of my own work on the issue, I’ve spoken to several junior faculty and students who have had remarkably similar experiences with senior scholars. In many cases, someone might send a paper to a faculty member in advance of a conference, for instance, in the hope of engagement and collaboration, only to get no response but to see their work later appear in their field’s major journal, under the professor’s name. Others report that senior faculty attend their presentations at conferences, take notes, leave without engaging and publish essays with key arguments and analyses that were clearly filched from the students’ work.

Why does this persist and why are there no safeguards against such behaviour?

It is incredibly hard, if not impossible, for the outside world to understand how much power resides in a single line on an academic CV. One publication in a field’s “top” journal can outweigh five in those seen as “lesser” publications, and not annoying powerful names in one’s field is a mode of survival: someone like Shakespearwallah might be the one to write you a recommendation letter or access to an archive down the line, in a career that many still see as lasting the rest of their lives. Academics, with their many research subsets, operate in very tiny, insulated worlds where the vast majority of job applicants don’t have a choice about where they can work: contacts, bylines, and networks are everything. (Trying to explain all this to non-academic peers is an exercise in futility that often ends in drowning one’s sorrows in a large tub of ice-cream at midnight, watched with puzzled concern by one’s solicitous cat.)

This kind of plagiarism is rampant in mainstream publishing as well. For years, many on social media have complained about writers at “prestige” publications trawling their tweets and published links and filching their work.7Readers are familiar with content mill publications that construct entire stories out of Twitter threads — they might post images, but it is still just a cheap way to create an “article.” Often, a writer at such a place will swoop in on someone’s work, take a central concept and repackage it to viral fame, taking credit for the entire analysis. For instance, a lesser known critic, also an activist for victims of crime, might write several essays on her website or in “lesser” publications about how culture compels them to regurgitate stories of high drama, forcing people to relive their worst moments. A critic at Big City Magazine (BCM) will come along and filch this analysis and critique but repackage it and relocate it within film and television and with a quick, sexy term: the “drama plot.” This repurposing makes the BCM critic very famous, and she is soon anointed the originator of the entire analysis, having planted a flag on it like an explorer jubilantly posing for a selfie on top of Mount Everest while his irritated Sherpa rolls his eyes. Elsewhere, another writer might write about polyamory, a boring subject done to death, but filch an analysis from another writer, one that points out that the phenomenon is not some radical reconfiguration but just another way for capitalism to organise bodies in its service, and in no fewer than two essays. Suddenly, the first writer’s work is erased and the second becomes the originator of the thesis, having soft plagiarised it. The competition among writers to get to the gate first with “original” and potentially best-selling work is so insidious that even literary agents and acquisitions editors will get in on the game: one surprisingly common kind of theft, which I have written about in “Don’t Share Your Book Proposal,” is that of literary agents stealing the book proposals of former clients and gifting them to newer ones who may have more “name recognition” and who, like the BCM critic, are adept at repackaging. In such cases, agents and writers collude with acquisition editors who will have seen the proposal in previous rounds and know that it is stolen, but who will still happily sign off on the deal if they think they can make money off the book. Such theft doesn’t just harm the physical and mental well-being of the writers who see their work stolen but who lack the resources to mount a legal challenge: it can mean an end to their work and their place in the world.

Such behaviour, the deliberate theft of material from people who are powerless to speak out, is rampant in academia as well. I’ve spoken to researchers in the U.S and Europe whose legal standing as scholars on foreign visas was put at risk by unscrupulous senior faculty. Each case was depressingly familiar and eerily similar: a professor would lay claim to the scholar’s original research and literally write them out of the project, knowing full well that the latter, usually a graduate student, could not protest. Foreign graduate students are among the most vulnerable in academia: any disputes with senior faculty can lead to a loss of funds and visas forcing them to return to their home countries without completing their degrees, perhaps even leaving academia altogether if they cannot continue their work. Given the fragility of their situations, they usually give in to having their work taken away from them and are — if they are lucky, and if they have the time and resources — compelled to craft entirely new projects.8This has been recognised as a widespread problem in the sciences, but there is much less attention paid to it in the humanities, in part because research there is much less empirical and harder to pin down in terms of origins. Maria Toft’s Denmark-based campaign #PleaseDontStealMyWork includes testimony from a foreign postdoctoral student.

An understandably bewildered and shocked reader might be wondering: how can such practices continue? Why would someone like Shakespearewallah, a world-famous scholar, deign to even steal from a first-year graduate student? Why would a top critic at BMC filch material from a lesser known critic?

Let us be blunt and and not waste time wondering about “the mind of a plagiarist” or some such: plagiarism happens because publishing, like the world, is filled with some of the worst, pettiest, and cruellest people with a fundamental disregard for ethics.

It happens in the context of the collapse of the publishing world, and a perceived problem with scarcity of material. As even large venture-capitalist-funded entities like the Los Angeles Times and Messenger cut their staff, writers find themselves unable to think of new projects all the time. In a world where readers expect new material twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week and refuse to pay for it, publications are under pressure to keep producing “content” and, as a result, writers everywhere are constantly stressed about making themselves employable. While magazines like New York make it seem like the writer’s life is a glamorous one, the truth is that the average wanna-be writer, especially in cities like New York, lives in an apartment shared with six people and one toilet (which, if they’re lucky, is actually inside said apartment). The New York Times and the New Yorker boast an impressive array of names but it’s unclear, at least at the former, how many are full-time employees or, as one survey calls them, “full-time equivalent” employees — a term that seems to mean “not full-time, never will be.” Among their writing staff, for instance, a number have titles like “contributing editor” — a term that translates to, “a freelancer given a fancy title because she writes often enough here but who still has to hustle for speaking and adjunct gigs to make ends meet.”

The dark truth about the publishing world is that even well known writers are hustling several side gigs, but the top tiers are controlled by a few wealthy publishers and editors. David Remnick, the editor of the New Yorker, makes a salary of $1 million, and that’s a figure from 2005. Joseph Kahn, executive editor at the Times, is described as “fabulously wealthy” — he is the son of Leo Kahn, the co-founder of Staples, the office supplies company. While his salary doesn’t seem to be as high as Remnick’s, it also doesn’t seem to be a necessary one: pin money in the context of his vast fortune. As I have been pointing out for years, a publishing world filled with people who think money is not important because they have so much of it is also a world where writing and writers are devalued. And a publishing world that devalues writing and writers is one that encourages plagiarism. Eli Walsh, a reporter who worked at Messenger — a website that began with $50 million in venture capital money but folded after only eight months, has written that he “wrote 630+ stories in that time, most of them were just copying and pasting work that other reporters put time and effort into, just for us to swoop in and, essentially, steal it.” He continued, “It was, and is, deeply embarrassing and humiliating to know that you’re ripping off your colleagues in this industry for the sake of driving traffic at any and all costs.”

All of this is exacerbated by the unseen class hierarchies of the publishing world, less about money and more about status: there’s a distinct Upstairs, Downstairs atmosphere here where well-known writers will rarely deign to speak to or about those outside the rarified social and cultural networks they occupy and citing their work is certainly out of the question. In a review in the London Review of Books, John Lanchester notes:

“A sample observation, from Twitter: ‘A culture that is more or less custom-built to produce shameless, ruthless, notionally goal-oriented sociopaths is somehow still producing more and worse versions of that person than I thought possible.’”

Lanchester doesn’t name his source, but a quick cut and paste on the internet reveals that it’s from David Roth, co-owner of Defector Media. Lanchester cannot be bothered to give us that bit of information even though the observation is clearly important and striking enough for him to include in his essay. If Judith Butler had tweeted those words, Lanchester would certainly have named her as the source. In print, a few words like “David Roth, of Defector Media,” would have sufficed and the online edition could have hyperlinked to Roth’s tweet in addition to naming him. Instead, Lanchester displays his contempt for a lesser known writer, as if Roth were simply a faceless and emotionless butler holding aloft a silver tray from which the former wordlessly plucks a fresh flute of champagne. The point here is not, of course, that Defector writers should be treated as higher-status, but that these status assessments should not occur: even if Roth had not been “David Roth of Defector Media” and had just been “Roth, an IT guy who made a smart comment on Twitter,” it’s not acceptable to just say “from Twitter” as if Twitter made the comment.

Similarly, in academic journals, it’s not uncommon for grovelling editors (who are usually professors serving in honorary positions), hoping for validation from bigger “names,” to force junior scholars to scrub out the names of “lesser” academics in their articles and replace them with more famous ones. All of this proves what most academics know too well: the value of a theory or a school of thought is less about what it brings to the world and more about the networks of influence that raise some names above others.

At this point, the reader is no doubt wondering: what is at stake in all this? How can something as mundane as an obscure academic article read by, maybe, 50 people — usually unpaid, as is the custom in academia — or an analysis of a cultural phenomenon behind a paywall at some magazine cause such behaviour? Within publishing the myth of originality and genius holds particular sway, and is a form of currency, part of an economy where influence is currency.

To consider how this currency is created, consider this fictional example:

A Very Big Name (VBN) is hired by a university and the press release boasts about his hundred books and the fact that he is “an internationally known figure.” In fact, VBN has only written … one exceptional book. Every other book after that is an iteration of the first, a text that was groundbreaking in its time because it was the first to explore the rare phenomenon of Zoological Trumpetry among the Lalapalian Ergots, residents of a tiny island off the coast of Norlandia. Due to a series of circumstances, most of which involve VBN poisoning his academic rivals or simply making sure they only get jobs in the most obscure colleges with deeply under-resourced libraries, he has become the “foremost authority” on this subject. VBN is very good at navigating the academic machine of grants and fellowships and knows how to parlay the success of his first book into international fame. Grants beget grants and, soon, he is everywhere: academic centres in Berlin, London, Oxford, Harvard, and elsewhere all come calling. Zoological Trumpetry is now such a tiny but significant field (as VBN assures us) and the Lalapalian Ergots are such a very rare tribe and deeply oppressed (again, according to VBN), that funding his work becomes an urgent Social Justice Cause for many, taking on added urgency in a world where deans and provosts have begun to demand that all intellectual work be Relevant and Public Facing.

His overflowing coffers and growing influence allow VBN to persuade the university to hire a retinue of researchers — mostly underpaid graduate students who hope that their association with VBN will secure prestigious jobs, the sort they dream of as they take turns getting him his morning coffee and croissant, buttered just so. (Such researchers never, ever pay for anything out of pocket.) By the time he retires, VBN will have published two hundred books. Nearly all of them will be compendiums of sources and “research” slapped together by his “team,” under enormous and constant pressure to keep producing this work. Now approaching 90, VBN remains a fixture on television and the lecture circuit. He has not said anything new in over 199 books and, meanwhile, Lalapalian Ergots have mostly disappeared. Once, another academic submitted a paper in which he proved that they had grown weary of constant intrusions and gone extinct purely out of spite — but his paper was yanked before it saw the light of day.

VBN will continue to bully his way into prestigious gigs and feed off that one book until his death. Similarly, the BCM writer will get an award for inventing a term that in fact is based entirely on another writer’s work and feast for years on “Drama Plot.” When others — including the critic from whom she stole her central point — try to pitch articles or book proposals on the topic, editors will look at them quizzically and exclaim, “Oh, yes, but we already know this from ‘Drama Plot Lady!’”

This is what plagiarism does: it makes original and interesting work appear second hand when the originator produces it. Plagiarise the right way and you’re made for life. Do it the wrong way, and your entire career can come tumbling down, as Gay learnt.

Status begets status but poverty begets poverty, and soon the writer whose work has been stolen gives up and leaves the profession entirely. In these ways, plagiarism is a deliberate instantiation of power, connected to imperceptible resources that fuel the publishing world. And it creates a discourse that is more soundbite than deep and useful analysis.

Plagiarism is not about some bad apples failing to cite and acknowledge the work of others. In Marxist terms, it is fundamentally about the exploitation of labour and the extraction of resources. Today, as unionising efforts spread everywhere, more and more writers — in and outside academia — are conscious of how their work is not, as Elizabeth Gilbert would have it, the work of “Big Magic,” but grounded in capitalist enterprises. But too many still resist thinking about the mechanics of writing — how they go about it — as part of capitalism itself and fail to see how matters like plagiarism are part of the system, and much of their thieving behaviour is driven by a drive to earn spots in “prestige” publications, no matter the cost. High-status plagiarists feed on the intellectual labour of those “beneath” them the same way other kinds of exploitation under capitalism work, and in both cases there are no legal structures that ensures those who do the work get the benefits. In the case of plagiarism, the currency of those benefits is not always hard cash, it can also be credit, but credit turns into hard cash in publishing.

The examples I’ve described so far appear not in extreme right wing spaces but on the broadly construed left, ranging from liberal newspapers and magazines, to academic journals (those woke lefties!), to leftist publications that trumpet their social justice cred as often as they can. The problem is compounded by the fact that so few leftists, filled as they are with reductive ideas about class and the ennoblement of poverty, actually believe that writers should eat. The contemporary left is filled with this sense that only a suffering artist can make worthwhile art, with no regard for matters like food and shelter.

But a true Marxist theory of plagiarism is, first, founded upon the idea that the work of art, the act of thinking, the production of analysis — all of that requires food and shelter: Marx spent his winters pawning his coat, as Peter Stallybrass famously points out. It also makes it clear that the act is not simply about the theft of ideas (which is serious enough) or bad individuals, but about the powerful exploiting the less powerful who cannot fight back and whose labour makes possible the profits enjoyed by those of a higher class status. The dynamic is common across all the cases seen so far: the Times exploits smaller, local papers which depend on freelancers who don’t have the resources to fight a media behemoth; the LRB (funded by a family trust fund) deftly swipes the words of lower-status writers on Twitter without naming them, and professors steal the analysis and labour of graduate students who are the least able to even protest the theft of their work. In each case, the ideas are produced by the intellectual working class and appropriated by the intellectual ruling class.

The Claudine Gay matter did not expose and end the rampant practice of plagiarism: it only obfuscated the fact that plagiarism is about the exploitation of labour and the pilfering of resources.

III. Change the Water

What can we do about this state of things?

In “Uncanny Valley of the Dolls,” an episode of the show Elementary, Sherlock Holmes (Jonny Lee Miller) and Jane Watson (Lucy Liu) discover that the killer they seek may be one or all of a group of graduate students furious with a professor who took credit for their work.

Let us be clear: murder is never the answer. But who amongst us, seeing our hard work swiftly and quietly repurposed in the words of others, has not had murderous thoughts? How can we smash the ever-humming machine of plagiarism without resorting to the most drastic means?

When writers deliberately excise the names and work of those they consider beneath and outside desirable spheres of influence, they are violently erasing and supplanting the intellectual contributions of others whose knowledge and expertise makes their own possible. This is theft, and rather than waste any time in asking writers to change their ways, we need to make it deeply uncomfortable for them to continue with their thieving ways, which means fighting back against plagiarism and holding plagiarists accountable. At the same time, if we are to think constructively about ending plagiarism of all kinds, we have to fundamentally realign how we think about knowledge production. That includes adopting preventive methods. In a 2002 Science magazine article about mentors stealing the work of junior scholars, Drumomnd Rennie, then the West Coast editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association ( JAMA) was sympathetic to the exploited, but he also told the magazine, “They know their adviser is stealing their work, but they think they need to stay and get a good recommendation…I tell them, ‘If you work with a thief, you get what you deserve.’” I agree with Rennie — if you work with a thief, hoping that he might give you something in return for his theft is foolish. If you can, find a different, better mentor or adviser — and if you’re in a department or at a publication filled with people who are all equally rapacious and uncaring, you should find a different workplace altogether because the struggle to keep your sanity in such an environment will only result in the worst possible scenario(s) down the road. I don’t mean that we should from now on record all our conversations or walk around with little machines that project ™ and © symbols above our heads every time we think we’ve hit upon original ideas, but that we start thinking more consciously about how we trace our work within discursive communities.

Keep track of your work and where you send it, and don’t mistake social media for any kind of “community” — for plagiarists, a place like Twitter is a field of opportunity for theft. Be wary of senior researchers or writers, who are not above filching ideas, analysis, and sources and who will try to intimidate or lure you with vague promises of advancement, threats, or collaboration. Be aware that all projects leave forensic trails: it’s not impossible to trace origins back to you. Amy Westervelt, for instance, didn’t just see her original story scooped by the BBC: she was told by sources that the outlet had misrepresented itself to them, by telling them that Westervelt was part of the project, and that was a major reason why the sources even spoke to them.

There is of course a way to navigate this uneasy terrain without descending into paranoia — I will suggest that social media, where terms like “mutuals” and “followers” dominate, has deluded a lot of people into a false sense of “community.” Keep your friends close, and the rest as far away as possible — reconsider the idea of community to mean people you actually know and trust.

Think about citational practice not as a payment of tributes to Very Important People Who Might Get Us Jobs but as a genuinely reflective way to consider that knowledge production is not a magical process but born out a vast network of thought. Attribution and citation need to become part of the DNA of everyday discourse and publishing, and scholars and writers need to think about ideas, not people, as critical to their discursive practices. Another way to put this is that you should cite even the people you dislike or with whom you disagree, if their work and formulations actually have a bearing on your own. (Unless they happen to be people who plagiarised your work, in which case you owe them nothing and you can give yourself permission to tell everyone you know why you don’t think they deserve to be cited anywhere.)9The same is true of people who plagiarise the work of people you hold dear: I once found out that a scholar whose work I admired had plagiarised the work of a friend. I threw the plagiariser’s book into the trash and never referenced him again.

Margot Weiss in “The Interlocutor Slot: Citing, Crediting, Cotheorizing, and the Problem of Ethnographic Expertise” points out that “[c]itation repeats and retrenches authority, reinforces power, creates the canon within which we learn how to marshal our own authoritative speech and that “we need to pay more attention to our politics of attribution.” Such attention is often scant, even in the most supposedly left spaces. When I first saw John Lanchester’s review, I wrote to the editors of the LRB suggesting, for the reasons already outlined above, that they should name him and also provide a hyperlink.

To my great surprise, the editors Jean McNicol and Alice Spawls wrote back almost instantly, and said they were considering my letter for publication. That this never happened is not a surprise — print space is limited, after all and the LRB, as far as I can tell, only publishes online the letters it can include in its print edition. Still, I was surprised to see no change at all in the piece, no hyperlink, no note at the end — easy enough to do with the online edition. Recall Westervelt’s question: How are you going to stop extractivism while being extractive?

The LRB has avowed leftist politics — and it is still among my favourites — but what does it mean to be on the left and not act upon a matter as simple as citing the name of a source, to be a publication that reproduces the hierarchies it claims to contest? The LRB’s act of not naming Roth is a smaller matter than, say, hijacking and presenting his words as Lancherster’s own (which never happened, to be clear) but it is still a significant omission.

So, what is to be done? No amount of ideological shifts and changes will help if plagiarists don’t understand that they stand to lose something for their acts. Professors who exploit students as they swan between prestigious jobs at prestigious universities don’t have to care because they know that no one in their circles will dare support an accuser. Writers and agents and collusion acquisitions editors will continue to steal the work of those they think are too powerless to fight back. Researchers will continue to bully junior faculty and students out of projects. Magazines will encourage their writers to filch ideas from “lesser” scribes.

While successful lawsuits have been brought against scientists, such cases are harder to prove in the humanities and in mainstream publishing — but not impossible. Certainly, the Times and other such publications have fleets of lawyers but if enough writers everywhere begin to protest and consider legal challenges, editors and writers will at least be persuaded to think twice before continuing to engage in any kind of plagiarism (freelancers are held liable for their own work). Copyright and intellectual property laws are simultaneously very complicated and very simple — explaining that in more detail is beyond the scope of this essay.

But the point remains: that publishers and writers will only pay attention to lawsuits, or the threat of such — at the very least, it’s a damn inconvenience or a distraction and a series of them can be time-consuming. In a perfect world, writers who are proven to have plagiarised will have to pay damages of some sort, and this should be retroactive (it might take years for someone to feel secure enough in their fields to even think of a lawsuit). If even a single academic can be sued for filching the work of a junior scholar, a single critic sued for repackaging the work of another, the shock waves alone might at least create different policies in universities, protective measures for vulnerable foreign and native students otherwise too scared to fight back, a measure of protection for writers.

I have no doubt that critics of such changes will refer to them as “chilling,” insisting that they will make public conversations and discourse less likely, that somehow people will be less inclined to share thoughts and ideas. But where does this grand public sphere exist, if the only people who can afford to write are those of independent means, when all the publishing houses are slowly morphing into one, and publications and entire university departments are disappearing? People who refer to attempts to protect writers as “chilling” remind me of the men who decry sexual harassment laws as somehow inimical to some idea of free love: as if the unwanted hand on the bum is not more chilling than the attempt to take it off (or break it in three different places).

Plagiarism is a symptom of an exploitative, extractive economy: to end it is to rectify an imbalance of power. To return to David Foster Wallace, “the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.” I repeat: a publishing world that devalues writing and writers is one that encourages plagiarism. A publishing world dominated, as it is today, by plagiarists, is also one where standards for accuracy have fallen so far that readers cannot and should not rely on most writers to render an accurate picture of the word. A magazine or a laboratory willing to encourage plagiarism is also one that will falsify information and data, to dangerous effect. For too long, the publishing world has worked on the assumption that the exploitation of the less powerful by writers who have more power is simply the reality we must accept: this state of things needs to end. The only way to create change is to change the water.

Author Bio: Yasmin Nair, a well-known writer and satirist, has been widely published in the world’s most prestigious publications including The Atlantic, Harper’s, the New Yorker, the New York Times, and Vox, under a range of pseudonyms. She has, also pseudonymously, received commendations and awards from the National Book Critics Circle, the New York Press Club, the Pan African Literary Forum, and the Robert B. Silvers Foundation. This essay, in various shapes, will soon appear in several publications including those named above. Nair has been invited to speak at Harvard, twice, and refused each time because the university, despite its $50 billion endowment, would not pay for her to speak.

With many thanks Hena Mehta and Nathan Robinson, whose ideas permeate this work. Any problems and errors are mine alone.

If you need legal help with plagiarism, please consult a lawyer (a real one, not your cousin in law school). In Illinois, Lawyers for the Creative Arts does fantastic work for those who reside in the state; look for similar organisations where you live.

For more, see:

“Don’t Share Your Book Proposal.”

And anything here.

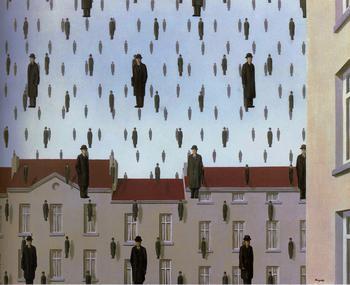

Image 1, Golconda, René Magritte, 1953.

Image 2, Not to Be Reproduced, 1937.

Image 3, The False Mirror, 1928.

This piece is not behind a paywall, but represents many hours of original research and writing. Please make sure to cite it, using my name and a link, should it be useful in your own work. I can, I have, and I will use legal resources if I find you’ve plagiarised my work in any way. And if you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.