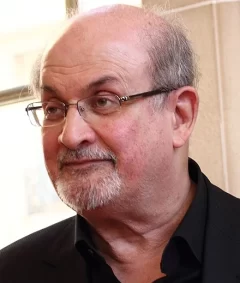

I remember buying my copy of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses and rushing with it to my dorm room, excited about finally reading the much-debated text that had caused so much turmoil and resulted in the infamous fatwa. I was disappointed, to say the least. I don’t have my copy any more — sold or given away, or perhaps in a box in my storage space, preserved as an artefact of some long ago time. I’ve returned to it a few times over the years and never been inclined to get beyond a chapter or two. I also read his Midnight’s Children — in a grad school class, as I recall — and found it just boring. By then, I’d also grown to loathe Magic Realism as a genre. All of it was just too precious: a lot of mish-mashing of voices and narrative techniques disguised as some kind of deeply authentic Voice of the Other, aimed mostly at white readers who want to be reassured that the text they hold in their hands is something, you know, authentic and supposedly nothing like the canonical works they were raised on. Rushdie, it struck me, was the kind of writer who fascinated Western audiences and probably bored most of his native ones.

My evaluation of his work has nothing to do with what happened: the fact that he’s not really a great writer in my estimation doesn’t mean that I’m not absolutely horrified at what happened, as we all should be. The news is shocking and devastating. Here is a man who spent nearly ten years under a horrible fatwa, hiding and escorted by a security detail wherever he went, his entire life upended as he sought to live as normal a life as possible. The edict was finally lifted in 1998* but, as we now know, it has effectively in one way or another been in place for too many people: in The Atlantic, Randy Boyagoda points out that Rushdie’s attacker, Hadi Matar, is only twenty-four and wasn’t even born when the fatwa went into effect.

One response to the attack, the dominant one so far in liberal and left-ish media, has been to once again hold up Rushdie as the epitome of Literature with a capital L, a writer who represents everything that is noble and good and enlightening about Writing with a capital W. Boyagoda suggests that the best way to “demonstrate our solidarity with him” is to “advance the principles he embodies by committing to literary works bold and ambitious enough to make the very acts of writing, publishing, and reading once more daringly world-changing, even, if must be, dangerous.” I suggest that, instead, we start thinking of literature and writing not so much as “world-changing” or “dangerous” but as forms and acts that are far more mundane, more quotidian. Literature and writing — whether fiction or nonfiction or any blend of the two — don’t just stand against political and cultural structures to illuminate them: they are also part of them, even when written in resistance.

Boyagoda is a former president (2015-2017) of PEN Canada, an organisation that consistently speaks on behalf of writers “persecuted, imprisoned and exiled for exercising their right to freedom of expression.” This is all well and good and even, arguably — consider what just happened — necessary. But perhaps we are better off dispensing with this idea of Literature and the Role of the Writer as somehow sacred and “world-changing.”

There’s a long tradition of writers holding themselves up as magical beings whose work on earth is to show mere people how to be better humans: how to be good or bad or how to change themselves and the world. For many of us, reading has in fact been transformative and even, dare we say, magical in the way it has transported us into other realms, certainly. And a world without literature or writing would be a sad and incomplete world indeed. But a work is not “world-changing” simply because some take offence at it. Satanic Verses was not denounced because millions of Muslim across the world saw a threat to their faith: the denunciation was as much a power move by Iranian officials as it was a statement about religious purity (about which there has always been much debate within the faith). In its aftermath, it has continued to create havoc and resulted in the deaths of nearly fifty people worldwide, including those killed during riots incited by its publication.

Boyagoda notes that criticism of the attack has come from a “spectrum of public figures—in the U.K., Prime Minister Boris Johnson and the novelist Ian McEwan; in the U.S., New York Governor Kathy Hochul and PEN America President Ayad Akhtar. This is a rare chorus. Politicians and artists tend to regard one another with suspicion, even contempt.” Well, actually: it’s not a rare chorus and this is a naive understanding of what these responses mean. Certainly, it helps Rushdie to garner such support but we ought to pause and consider, for instance, that Boris Johnson’s denunciation is a result of his anti-Islam and anti-immigrant sentiments. While we might not detect the same prejudice in everyone who supports Rushdie, we have to pause and wonder about the implicit message behind such statements: Islam is against the freedom of the West and represents everything that is evil, and only the West can support “freedom of expression.” In the United States, such undifferentiated yet palpable expressions of anti-Islam sentiments have meant a further marginalisation of Muslim men in particular and the further surveillance of mosques and other community spaces as potential hotbeds of violence and terrorism (while Christian churches are ignored despite evidence that they’re actually fomenting violence, racism, and misogyny).

As for “freedom of expression”: what does that really mean in a literary and publishing world increasingly dominated by a handful of very large publishers, currently embroiled in a lawsuit to determine whether or not the five biggest of the lot can dwindle down to four? Writers like Boyagoda and Rushdie are among a tiny number of people who don’t have to worry about making a living from their work: Boyagoda is a tenured faculty member at the University of Toronto and Rushdie is, well, Rushdie. Increasingly, the only people who can afford to write anything at all, to engage in any kind of expression leave alone anything “world-making” or “dangerous” (whatever all that means) are people in already secure financial situations. And what does “dangerous” mean when all around us all we see are mostly fiction and non-fiction works that cater to the most insipid tastes? I’m reminded of how many truly awful “anti-racist” books became bestsellers during the George Floyd protests and after. The vast majority of these were insipid and insincere and manipulative … but, oh, they just looked so cool in your Zoom background as you discussed yet another trivial office management problem during yet another needless online meeting.

Rushdie is, mercifully, on the road to a very long recovery but may have lost an eye and will probably need a lot of hospitalisation and therapy of all sorts for many years. I grieve for him, for what I know will be an unbearable sense of dislocation in the world, as I would grieve for anyone in a similar condition. And, at the same time, the struggling writer in me also wonders: who will be paying for his undoubtedly overpriced and expensive treatment? It’s possible he has the healthcare and the means for such and yet it won’t surprise me if the costs become so enormous that someone has to eventually organise a fundraiser for him: unfortunately for Rushdie, he no longer has access to the National Health Service and must depend on the horrendous system that counts as “healthcare” in the U.S. I don’t bring up this point to be cynical but to emphasise that Literature and Writing and Writers — all those things and people we insist on placing on pedestals as if they are simply self-evidently so — are in fact part of very material conditions and systems.

Part of acknowledging such conditions and systems and of actually changing the world has to do with refusing to think about writing as an act that is inherently dangerous and world-changing. Many of us understand how transformative the simple act of reading can be and we approach the world on intellectual and psychological and political and cultural pathways somehow awakened in us via what we read as children, and what we read as adults and what we ask children around us to read (Boyagoda has a interesting essay on reading Enid Blyton as a child). But for the sake of Rushdie and all other writers from here on, let’s stop thinking about writers as divine angels of our time put on earth to resist tyranny everywhere. Writers are symptoms and manifestations of their times, not special snowflakes. They don’t need the burden of world-making on their shoulders: what they need is the kind of economic support that, at this time, is not only declining but under threat because publishing is increasingly becoming the province of the well-off.

Boyagoda and many of his kind reinforce the idea that writing just happens and that it has meaning beyond what we can fully grasp until something as horrific as this attack comes about. But what if we worked on changing attitudes to writing and “Literature” so that they were seen as everyday acts that happen to also give us pleasure and are occasionally enlightening, producing works that are sometimes infuriating but are, in the long term, just that, writing? Perhaps, then, we might no longer face the reality of the long-term effects of fatwas. What if someone was furious at a work of art, any art and we could simply say, “Dude, it’s just a novel, maybe chill,” and they actually just chilled or were calmed down by their friends? What if that happened on a global level, between countries?

There’s a set of writers and publishers who need to insist that Rushdie makes it clear that Writing is Very, Very Special. It’s not. It’s a craft, yes, and so is welding a pipe properly (spend some time watching a skilled welder do this, and you’ll see what I mean). It’s an occupation, and it needs to be respected as such. It’s labour, and needs to be compensated as such. Are ideas and writing dangerous in some contexts? Yes, of course. But if we keep harping on this idea of writing as a potentially radical and disturbing act, what happens to our vision of a world where no one will be persecuted for it?

For now, let us all hope for Rushdie’s swift recovery and also be cautious about echoing the conventional “Civilised West versus Savage Muslims” narrative that’s being fed to us in sometimes very subtle but nevertheless harmful ways. Boyagoda insists we should read Rushdie to support him, but why? We can and should support Rushdie whether or not we read him (I have no plans to do so). And let us also begin to think more expansively about writing and its place in our lives. Can writing change the world? Of course it can, in so many ways, most of them intangible. But it can’t do that as long as we devalue its worth and as long as we refuse to think of it as part of a political and economic context. Writing and Writers are not special, but the world we envision as better than this one is, and we have to keep working towards that one.

*Kinda, sorta, not quite. What the Iranian government said was that it would “neither support nor hinder assassination operations on Rushdie.” Edited August 15.

For more of my writing on writing and publishing, see this category, “On Books and Publishing,” on this website, for starters.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

Image via Wikipedia.