“More Mean Girls than Norma Rae.”

On August 18, 2021, five people posted a public letter claiming that they had been unceremoniously fired from their jobs by Nathan J. Robinson, the editor in chief of Current Affairs magazine. The following is a full account of what actually transpired at the publication. I have tried to leave out as few facts as possible, to answer every question anyone might possibly have about the stories that have been told, and explain why I still support Current Affairs. If you would just like a brief summary version, read this.1 There will doubtless still be questions or requests for clarification: I will not respond to any on social media walls or threads. If I think a question merits a response, I will post the answer in the appropriate section of this piece, noting the addition (or change). I will not “engage” or argue endlessly with anyone online.

As someone whose nearly thirty years of writing experience includes investigative reporting, I’ve embarked upon this project with the same approaches, tools, and methods I would use for any report. I’ve looked at many internal documents including the emails that flew around at the time, recordings of and notes from various meetings including an August 2021 virtual retreat, and in-person and email conversations with people involved. I approached every former board member, every signatory on the public statement, and every recipient of severance money with a request for an interview. None of them responded.2 I have used my experience as a writer and journalist to produce a forensic account based on a thorough examination of documents and correspondence.

This has taken a very long time to write in large part because I’m a freelance writer and this is unpaid work I’ve done on the side, so I’ve only been able to work on it in short bursts. I write this as a longtime contributor to the magazine, its editor at large, and as someone who has written about left labour issues in publishing for several years. My editorial position is purely an honorary (unpaid) one, like the Queen Mum but without the hats and jewels of the Empire. I am either friends with or on very friendly terms with a number of the people still associated with the magazine. I have talked to many people affiliated with the magazine, past and present, and some have seen drafts of this piece but I am writing this of my own volition and independently of any editorial oversight at Current Affairs. I’m friends with Nathan, whom I also consider both an ally and a comrade but that is not why I’m writing this. If I thought at the time or later that events had transpired as described by the media and the departing staff, I would not have hesitated to leave CA in solidarity with them. Even as a friend who cares about Nathan: if I had ever thought that he was an inept and fake editor and socialist, I would have persuaded him to leave publishing altogether and, perhaps, retire to grow marrows like Hercule Poirot, or tend to a koi pond. If I didn’t know that he has now significantly restructured things to be different, I would not still be an editor at large and ally of the magazine.

While I know Nathan the best among everyone concerned, I was not driven to write this by loyalty to him but by the desire to present the more complex truth of what happened. When I began writing this, I did not think that one side or the other was more or less culpable in what happened. I genuinely believed that much of what occurred had come about because of a fractured workplace environment that made the day to day operations of a small but complex publishing entity nearly impossible to sustain, causing several professional and interpersonal relationships (which had intertwined in unproductive ways) to shatter and turn hostile. Yet, even then, I was disturbed by inconsistencies between the August 18 letter and what I knew of the details behind the scenes. The immense amount of material and information I’ve gathered over the last several months have led me to conclude that the staff letter and subsequent coverage of the matter have resulted in a skewed and even malicious account of events. It was never any kind of foregone conclusion that I would end up being far more critical of the now former staff than of those who remain at the magazine. The facts have brought me here.

As difficult as it has been to wade through the many malicious fictions that have emerged around Current Affairs, this experience has also been deeply enlightening and productive: it revealed a great deal about the fragility of a left that understands systems of oppression but much less about how to build liberatory systems of its own. Nothing about what happened in August 2021 is as simple as the story that circulated first via Gawker and then on social media, a false and malicious tale that continues to haunt the internet. The account of what really happened is a complicated one and required a great deal of excavation of original documents, analysis, and more. This is not a short article but it is worth the time and effort to read it carefully (along with the many footnotes). The history of what happened has been written via a torrent of malicious and mendacious tweets over the course of the last nineteen months. This document provides a history based on facts. It is not meant for consumption by trolls on social media in short bites, but for the adults in the room.

A Cravat, A Cravat!: Current Affairs Breaks The Internet

It was the hot, torpid summer of August 2021. The pandemic had increased people’s sense of isolation and boredom, the economy was unstable, and unionising efforts were steadily garnering attention. Into this morass came a news story that burst onto the internet and never left. It had all the elements of a satirical novel and seemed to prove to many that the left betrays its principles and eats its own. As Gawker and others told the tale: Nathan J. Robinson, the editor in chief of a popular socialist magazine Current Affairs, unexpectedly and summarily fired his staff for trying to organise.

This allegation appeared in a bombshell August 18 open letter that ricocheted around the internet. Five people co-signed a public statement in which they claimed to have been “fired by the editor-in-chief of a socialist magazine for trying to start a worker co-op” and for “better work conditions.” The signatories were, as listed: “Allegra Silcox, Business Manager; Lyta Gold, Managing and Amusements Editor; Kate Christian Gauthreaux, Administrative Assistant; Aisling McCrea, former producer of The Current Affairs Podcast; Cate Root, Poet at Large (formerly Administrative Maven).”

As the story went: left penniless and with no idea how they would pay their bills, fired staff members were left begging for thin gruel in the streets. They and their online supporters insisted that Current Affairs was only a vanity project funded by Robinson’s parents and that the real work had been done by the fired staff while he, it was implied, lolled around. Gawker described him as “a man who wears cravats and allegedly has a fake British accent.”3 Some version of “Socialist Editor Squashes Efforts at Unionising” was a standard headline, delighting many on the left and, certainly, the Right, whose various outlets chortled that this was an example of why socialism could never work. The story became increasingly farcical and was soon replicated all over the internet. Even now, Robinson is painted as The Boy King, flying out of his castle every day in a chariot drawn by five hundred chinchillas, cravats and bespoke suits fluttering in the wind as he leans out of the windows maniacally laughing at the minions who toil below him.

Spurred by people’s general desire for excitement after being trapped indoors for 18 months, the Current Affairs story careened around the internet like a game of Telephone, eventually bearing no resemblance to the original facts. Robinson’s sartorial style—elaborate and colourful suits with matching pocket squares—became a potent visual emblem of Everything Wrong With Rich People Who Treat Their Workers Badly: it was often unclear if his primary sin was that he wore cravats and had an accent, or that he had allegedly fired unionising workers.

Current Affairs published its first issue in March of 2016, a year that also saw the election of Donald Trump, who rode a seemingly unstoppable wave of outright fascism, and the waning of a Bernie Sanders-led craving for a socialist alternative. Over the next five years, the magazine would become a place to express and disseminate socialist ideals and it was widely seen and recognised for both its style and content. Consequently, its seeming implosion made for excellent news content—mostly written by careless “reporters” who didn’t want to examine the veracity of the salacious stories told by the departing staff members.

Eyeballs are the currency of websites, and these stories were effective clickbait; but few reports probed too deeply into the claims of the letter, the actual facts, or the aftermath of the incident as described. No one was fired, and there was no organising to start a co-op, a union, or any other worker-led collaborative.4 What happened at Current Affairs is not the story of a malevolent overlord oppressing his minions but a much more mundane one about the inevitability that befalls too many left institutions: the magazine was upended by what Jo Freeman has termed “The Tyranny of Structurelessness.” This is the mistaken idea that informal structures with ill-defined positions are truly radical and leftist while those with systems of accountability are not. “Evil, Loathsome, Cravat-Wearing, Fake British Socialist Fires Employees For Trying To Start A Union” is a far more exciting and sexy headline than “Socialist Magazine Struggles To Find A Coherent Structure And Things Come To A Head And Explode.” Or, “Socialist Magazine Falls Prey To Various Structural Problems.”

What happened at Current Affairs was that a burgeoning socialist magazine became unexpectedly successful in a very short time and, despite being led by a passel of lawyers, failed to develop a formal organisational structure. By the time the staff gathered for a virtual retreat in early August 2021, tensions and questions over and about how Current Affairs would be structured had been bubbling for nearly all of its five years, and were inflamed by the stress of the pandemic. There was a messy explosion that emerged from conflicting opinions and views on what the magazine and its organisation could and should look like, exacerbated by the fact that there were no structural processes in place.

Robinson had no small part in what happened. But everyone else involved has shielded themselves from even the appearance of responsibility by backing away and claiming it was all him—that he was the cause, instead of a symptom.

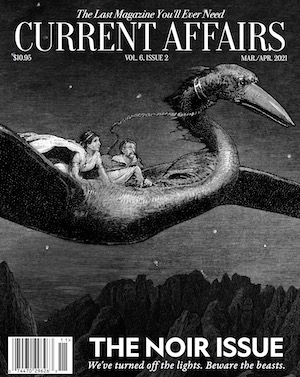

Few writers investigated the details of what happened. If they had, they might have discovered and reported that Cate Root was not in fact an employee at Current Affairs at the time, making her presence as a signatory a mystery. They might have reported that Lyta Gold was, at the time the letter was written, on the board of directors and was also the managing editor, which meant she was technically someone to whom other “workers” answered. The claim that the “workers” had been fighting for “better work conditions” evoked a Dickensian image of labourers speckled with soot and dust while the overlord sipped tea and nibbled scones in an upstairs lounge. But despite these allegations, no details about bad work conditions appeared in the letter: nothing was said about payment, benefits, or hours, for instance. No journalists bothered to follow up and report on the $76,014, in total, paid to various people, an amount that, for individuals, represented about five months’ salary for former staff members. The money even included a month’s salary for another person, Sam DeLucia, who had not even begun work at the magazine, and it represented 34% of its bank holdings at the time.

If the “reporters” had done their due diligence, they would have had to report that the departing staff knew, by August 11, that they would be receiving a severance if they decided to leave (they requested, via Lyta Gold, a lump sum over a payment over instalments, and email threads indicate no dissension). An email from Robinson to the staff and board, dated August 13, proposed a sum of nearly $240,000, to all of them in total, to cover everyone’s severances, to be paid out over a year. He explicitly stated that he would take on whatever part of this amount the magazine could not pay as a personal debt, paying in instalments.5 And on August 19, the board of directors stepped in with a public statement to assert that, in fact, no one had been fired:

But by then the rumour mill had swung into full force, expedited by several concurrent streams of toxic commentary and lies by the departing staffers.

Two reports, one by Alex Cypher and another by Hunter Walker, deviated from the norm, and presented more nuanced accounts. Walker’s article quotes an anonymous editor (not me!) who gave a different and more likely picture of what had happened, that the workers co-operative idea was only one among many options being considered, loosely: “All these things are always complicated and I don’t think this was necessarily a case where Nathan is a complete villain or where this is an example of socialism failing…This is sort of like organizations have a lot of dysfunction and sometimes it turns out very poorly.” The truth is a massively complicated story.6

When matters first exploded, I felt deep sadness and shock for all concerned but especially—at the time—for those who received the emails from Robinson, and I certainly felt that things could have been handled in a much better fashion. But I also saw an editor in chief apologise endlessly for what happened and bend over backwards to make sure that the departing staff got the restitution they wanted from the magazine, and more. In the spirit of Restorative Justice, as outlined by Mariame Kaba and others, my hope was that everyone would get the compensation they needed and that once a financial settlement was reached, they could move forward in their own careers. Instead, to my dismay, the departing staff and many of their online supporters unleashed a Tsunami of Spite and misrepresented what happened, tarred the magazine and everyone associated with it as scabs, evoked racist narratives about both Lily Sánchez (the current managing editor) and me, harassed Robinson in his neighbourhood, and successfully called on others to do the same.

It has, sadly, become clear that the outgoing staff members (who have never revealed their settlement) have no interest in justice: their only motive is to exact revenge even by lying and, if possible, to bring about the end of Current Affairs.7

This constant lying about the organisation needs to stop.

Former staff have been unrelenting and unscrupulous in spreading the most blatant lies about what happened and the structure of Current Affairs. For instance, on August 19, Kate Gauthreaux posted this on Twitter:

They (Gauthreaux’s chosen pronoun) also tweeted that they had no idea how to pay September’s rent when in fact, as email records and the board’s statement indicate, the staff had already been told they would be paid through September and that they were assured of a severance payment (in Gauthreaux’s case, amounting to $11,250).

Gauthreaux’s partner Jack Reno Sweeney jumped into the fray and spread even more lies in response to someone who referenced the fact put out by the board that no one could be arbitrarily fired from Current Affairs:

Gauthreaux and her partner lied unequivocally. It’s unclear what she’s referencing with “CA staff does not get paid equally.” If she’s referring to salaries: all staff were and are paid the same, $45,000 with health insurance for those who want it (Gauthreaux and Gold did not take healthcare payments because the former was on their father’s plan and the latter on her husband’s). If she means severance payments, “the rest of us get nothing” is a blatant lie. As Gauthreaux’s partner, Sweeney had to know that a severance was on the way, that no one was fired, and that Robinson—who had founded the magazine and was working with the board to come to a conclusion about severances— was hardly “AWOL & unable to do it himself.”

But the lies were also being disseminated internally: in an August 20 text message to Lily Sánchez, the then newly hired online editor, Adrian Rennix informed her that “staff were manipulated and lied to and realise their chances of severance money are slim” when, in fact, they (Rennix’s chosen pronoun) had been in discussions with the board and staff (as the latter’s appointed representative) about amounts. Similarly, when asked about the severance payment, Gold has described it as “small”: an amount that added up to nearly five months’ salary (plus healthcare costs for those enrolled), representing 34% of the magazine’s money, is not “small.” She also noted that Robinson had “made it untenable to go back” but did not clarify what that meant. This statement also suggests that they did in fact have the choice to return (and this was actually the case: they could have had Robinson ousted and taken over the magazine, among other options).

Tweets and Instagram posts may seem irrelevant and dated, like ephemeral radio signals across an ocean during World War II, disappearing into the ether and the swarm of newer posts. But ephemerality and gossip are exactly the point: social media has a way of constructing narratives that eventually stand in for the truth, long after even the tweets have been made to disappear. Over the intervening months, it appears that Current Affairs gossip about Robinson has become for some a valuable commodity. In 2022, Jaya Rajamani (once Jaya Sundaresh), a former freelance contributor to the magazine, responded to a request to spill “hot gossip” about Robinson. 8

Here, Rajamani is like an Englishwoman in 1940s London exchanging silk stockings for two packs of butter, except that her stock in trade is gossip: by posting this to an Instagram story, she is suggesting to people that she has troves of it about Robinson, attempting to further her credibility as an Influencer of sorts. If eyeballs are the currency of social media, gossip is the main commodity.9

Cumulatively, social media posts still circulate, zombie-like, in the form of rumour and innuendo, creating a kind of Dark Web of shadowy but persistent memory within which larger lies can continue to live on. Like the Sea Squirt that eats its own brain, social media technically has no memory and is constantly subject to erasure. Yet social media (and Twitter in particular) also do a lot of damage, serving as the ballast of lies and fabrications that keeps the Ship of Slander upright. Lies about Current Affairs remain persistent and unopposed, and no one in the media bothered to really investigate the claims. To this day, writers, artists, and potential subscribers have written or posted publicly that they are hesitant to engage with the magazine in any way because of what they’ve heard about its “union-busting” ways. There is no detailed counter narrative present anywhere.

Tweets can also create outright hostility and physical danger for their physical targets. In December 2021, Sweeney suggested that people should harass Robinson at his gym.

Then, on February 14, 2022, Sweeney followed Nathan into a local bodega, where he shouted at him and was promptly chased out by security. The experience understandably left Nathan shaken since it represented a spillover from the virtual world to a very palpable real world and a physical threat. Sweeney boasted about what he had done in a tweet, to which Gauthreaux responded:

Clearly, Robinson is the aphrodisiac glue that binds these two together but beyond that, such an open boast about harassing someone in a public space only encourages other online trolls to take matters into their own hands in real life, under the guise of enabling some brand of “socialism.”

Sure enough, a couple of months later, as Robinson was walking in the neighbourhood with his parents, a man yelled out “Nathan Robinson, go fuck yourself!”, on the street and in broad daylight. I have no doubt that this person was inspired by Sweeney’s call and action.

In later months, Rajamani, responding to a tweet actually unrelated to Robinson (a man describing his preppy travel fashion in the Washington Post), tweeted, “We should have bullied Nathan Robinson more.”

To which Lyta Gold responded: “I’m always saying this.”

A full list of the falsehoods and deeply malicious ongoing commentary perpetuated by the former staff members and their supporters is impossible because it is so very extensive: I can only highlight key moments to show how a false narrative about Current Affairs has been weaponised by former staff and their friends and supporters, bolstered by the kind of childish and salacious character assassination that attracts trolls and helps to perpetuate the lies—while causing very deliberate harm to Robinson and his co-workers. When the story first broke, many readers and supporters were understandably angry and hurt: they felt betrayed by a publication they had grown to love and cherish. In that context, it was natural for many to express their rage and sadness online. At the time, even those of us who suspected that things were more complicated than the public story understood that there needed to be a period where shock, dismay, and anger found their outlets. We hoped that in time, when matters had subsided, some or many of us might be able to offer the truth about what had happened. But the former staff and their friends have been relentless in their mendacity and mud-slinging: for a while, like clockwork, Lyta Gold’s Twitter account would explode in rage-fueled tweets that perpetuated lies about Robinson every time Current Affairs published another issue.10 In these and other ways, the ongoing malice of former staffers and people like Rajamani has had the long-term effect, like a submerged stream of acid-laced water running underground, of eroding trust in a magazine that, like any other fledgling enterprise, has had its hiccups and missteps.

This is not, at all, to diminish the force of what actually took place. As will become clear, things did happen—Robinson did send emails telling people they were no longer employed at the magazine (he in fact had no power to decide this, a fact whose significance was downplayed for reasons detailed later)—but the fervent emphasis on the immediate and singular details and the illusion that this one event is all that mattered has served to obscure several structural problems within the magazine and on the larger left. In the process, the institutional history of a significant left magazine and a slice of left history have been distorted and erased.

Members of the erstwhile board have all remained silent and, as this piece will show, even bolstered the false stories about organising in order to deflect attention from the fact that much of what happened came about because of the board’s failures of oversight and decision-making. The board and former staff have used the rhetorical device of paltering: selectively disclosing things that are technically factually true but deliberately selected to leave readers with an impression that is, on the whole, untrue. So, for instance, right wingers will say that glaciers aren’t melting by pointing to the one glacier that actually grew in size. Or, as in the case of Pamela Paul’s “In Defense of J.K. Rowling”: the writer begins with a set of statements which seems to indicate Rowling’s support for trans people but neglects to add that she has explicitly stated that sex is an immutable concept. (That’s about as transphobic as you can get). In the case of the board of directors—one that included Lyta Gold—the tactic has been to state, over and over again, that Nathan Robinson “effectively” fired “his” workers.

The question most often asked is still, “Did Nathan J. Robinson actually fire his workers or bust a union?” The answer is no, but this only keeps any analysis at the level of a story about individuals pitted against each other. The question needs to be, “What really happened at Current Affairs?” That reframing makes it possible to glimpse the complexity of what happened in August 2021 as emblematic of not just one magazine, an organisation, and some individuals but larger issues endemic to left publishing and with left political organising as a whole.

How do we create and think about left publishing in a capitalist system that continues to atomise and brutalise us as we attempt to forge solidarity in its wake? How do we create socialist, left alternatives within capitalism when it controls so much of our lives and continues to thwart our attempts to build a better world?

How do we build a socialist magazine under capitalism?

ORIGINS

Any account of the fracas requires an accurate history of Current Affairs and how it came about.

In the nineteen months since the story broke, the departing staff of Current Affairs and their supporters have claimed, through insinuations and outright lies, that Robinson had nothing to do with the inception and work that went into the magazine.

In fact: Current Affairs began with a Kickstarter campaign in 2015 (during which it raised $16,000 the entirety of the magazine’s money at the start) by Oren Nimni and Nathan Robinson, old friends from their undergraduate days at Brandeis and roommates in Cambridge, MA. Its first issue was published in March 2016. Originally structured as an LLC with Robinson as sole proprietor, it became a C-Corp in 2018, collectively owned by the board of directors (this is separate from the editorial board).11 Robinson had waived his right to 51% of ownership with the aim of distributing power equally among members of the board of directors (which included him and Lyta Gold—who only joined the magazine in 2019—as staff representatives). The magazine’s revenues all go towards operating costs (including staff salaries and writer and artist fees) and related expenses (including merchandise). In 2018, the board and Robinson thought Current Affairs needed to be a C-Corp so that it would not be bound to rules about political endorsements, but the idea of becoming a nonprofit was raised again in subsequent years. Current Affairs has, from the start, paid all full-time staff equally (by August 2021, the salary was $45,000 plus healthcare for those who wanted it) and does not pay part-timers less than $20 an hour (the current rate). All employees, including the administrative assistant and the business manager, were allowed to work from any remote location, as long as they got the work done, and hours were totally flexible: Silcox worked for a month or more from Oklahoma in the early part of the pandemic, for instance, while Gold only worked from Queens.

The magazine is funded entirely by subscriptions and occasional donations and was created on Robinson’s laptop and packaged in the apartment that Nimni and Robinson shared; Robinson, in the early years, shipped physical copies to subscribers himself, from the post office.12

There are no shadowy benefactors and Robinson’s parents do not fund the magazine (they were among the 261 donors to the Kickstarter campaign, but that is where their contributions ended). Rosemary Robinson, Nathan’s mother, has been working, unpaid, as the treasurer and secretary. The magazine has had a no-paywall structure from the start: its open secret is that all of its articles and podcasts are eventually made freely available, after subscribers have had first access.

Going against the trend of publications moving entirely online, Current Affairs declared, in its founding promise, “Our chief goal is to produce something you will enjoy holding and gazing at…”. At the time, left publishing in print and online was generally and deliberately dour and boring (recall, if you will, those dusty, long tracts pressed into your unwilling hands by members of the long-gone International Socialist Organization), its ugliness seen as a mark of political will and seriousness. Taking its cue from Jacobin (with whom it shares a web developer), Current Affairs committed itself to the idea that a magazine of the left could and should be smart, witty, and beautiful.

The magazine’s staff never quite cohered as a working unit. As the magazine grew, it acquired a physical office in New Orleans, to which Robinson alone moved in 2017; until 2019, he was the sole person in charge of actually making sure the magazine was published. The staff was an odd mix of in-person and remote staffers, part-timers and full-timers, and vital decision-making and conversations were all carried out over phone, email, Zoom, or Slack channels. At the time of the August 18, 2021 statement: Cate Root, a New Orleans resident, had worked as a part-time admin assistant for a period in 2019 as well and then left, but was slated to return in September 2021 as a part-time freelance editor (she kept her honorary title of Poet at Large).13

Aisling McCrea, in charge of the podcast, was a freelance contractor working from the United Kingdom who began in 2019. Lyta Gold began writing for the magazine as a freelancer in 2017, and joined as a full time amusements and managing editor in 2019, working remotely from NYC throughout her tenure. Kate Christian Gauthreaux, also a New Orleans resident, worked as a part-time admin assistant from May to December 2020, and became a full-time admin assistant in January 2021. Allegra Silcox was the first employee who went through a formal hiring process; she was hired as business manager in early 2020, and moved to New Orleans. Root, Gold, and McCrea simply came on board at various times through informal means.

On the board of directors, Sparky Abraham (California), Vanessa Bee (DC), Oren Nimni (DC), and Adrian Rennix (Texas) were and are all full-time lawyers (Rennix was also the board president), writing and podcasting on the side and serving remotely.

By 2019, Robinson and Gold were the only ones actually putting the magazine together, working with writers and on layouts and design; Robinson was the only editorial person working in the New Orleans office.

By 2021, to the outside world (and even to me) Current Affairs seemed to embody the spirit of the times: a hybrid and vaguely international workplace with people spread out across the continental United States and one person in the UK. But the outward appearance of youthful mobility and flexibility hid the reality that a lack of structure was making it difficult for the magazine to function, and the resulting tensions were undoubtedly heightened by the uncertainties and pressures of a terrifying pandemic. In May-June 2021, everyone on the magazine’s general Slack channel (which included the board, McCrea, and Root, who still remained on it for unclear reasons) participated in a survey about restructuring priorities at the magazine. Responses indicate a general sense of things being well amongst them all with praise for the “radically egalitarian” workplace. Overall, people were happy and excited to be at Current Affairs but there was an urgent sense that there needed to be structural changes. Responses noted “no firm role definitions/expectations/commitments from varying types of staff, need more board members with more time to give, org structure makes no sense/not clear who makes what decisions.” Neither the survey nor the meeting notes or actual video (over three hours) from the August 2021 retreat indicate any priority given to either a workers co-op or a union as a solution to the identified structural problems.

A LEFTIST LEMONADE STAND

A major problem at Current Affairs was that everyone (except Rosemary Robinson) on the board of directors and on the staff wanted to be a writer, and that nearly everyone except Nathan Robinson saw the magazine as a group of friends working on a fun project rather than the serious endeavour of producing a magazine. In a tweet a few months after the August 2021 fracas, Vanessa Bee, former board member and frequent contributor, wrote ruefully of the “writing collective” of Current Affairs.

She also wrote about the “community” she had at Current Affairs and of “just getting to write what moved us.”

It also appears that Current Affairs was something like a camping trip or a getaway for many on the staff and board. Bee tweeted that she had showered during a meeting (something she’s unlikely to have done during her day job as a lawyer).

Bee was not the only one who showered during a call. During a January 2021 zoom call, Cate Root took a shower and appeared against her tiled bathroom wall in a towel and with wet hair (and gleefully informed the mixed company that she had done so—most of the participants sat in stony, uncomfortable silence during this period, looking away from the camera). The point here is not to shame anyone or to dwell on a minor issue but to point out that too many members of the Current Affairs team thought of the magazine as something more like a sorority, a writing retreat, or something like day camp, rather than a workplace.

Adrian Rennix also wrote about the magazine as a community and “a place to write”:

Even more recently, in November 2022, Lyta Gold, in a post on her Patreon about The Banshees of Inisherin and friendship, writes, with apparently no sense that she was at the magazine to work, not to be among friends: “I’d thought, at Current Affairs, that I’d finally found a way of working with other people that wasn’t dependent on a notion of service: that we could jam together and create new and interesting work, like Colm with his musician friends at the pub.” And, “When it comes to The Incident, I go back and forth about whether I was naive to think that genuine creative and intellectual friendships were possible without notions of service, use-value, destructiveness…I’m still not sure.” But how is a work relationship not transactional when you are employed at a magazine? The lack of structure at Current Affairs contributed to the perception that the staff wasn’t working for anyone. For Gold, working at a magazine was like working in a band, something echoed by Bee later when she tweeted this:

Despite what Bee, Rennix, and Gold say, a magazine is not a writing community or a collective or a band, and it’s not “a place to write”: it’s an enterprise made up of mundane details that need attending. A magazine about contemporary politics and culture is not a zine designed to allow a select few to use it to write about whatever might move them to write, whenever they feel like it: subscribers need to get copies regularly, and the content does have to reflect the times. Much of publishing requires attention to seemingly boring matters: are the subscribers receiving their copies? Has the copy been sent to the printer? Have the mailing lists and subscriber databases been updated? Is the insurance up to date? Are there enough paper towels and trash bags? Board members were able to partake of the glamour and hip cachet of “working” at a popular magazine of the left and to develop their own contacts and networks—but without the drudgery of the work necessary to keep the magazine going. While it looked like there was a large staff putting it all together, in reality and at the time of the fracas the actual publishing work rested largely on the shoulders of only two people, Robinson and Gold (Lily Sánchez joined as the online editor on August 2, 2021). For the rest, Current Affairs was a fun project, a leftist lemonade stand, almost child’s play: a process of brainstorming, podcasting, and writing socialism-driven articles that they could claim as part of a collaborative community.

In the months since August 2021 many, including board members like Gold and Bee, have insinuated that Current Affairs was merely a vanity project for Robinson.

This is a shockingly untrue allegation from people who know full well that he was working on the magazine long before they came on board.14

If anything, given how often the erstwhile board members wrote for the magazine and appeared on the podcast, it could be argued that they saw Current Affairs as their own vanity project, one that required them to do very little of the actual process work that went into creating the magazine.

I have found, before and after the fracas, that the Current Affairs non-editorial staff also believed that they were part of a writing community and that they were too good for their own jobs. Some months before August 2021, I noticed that the podcasts, ostensibly managed by McCrea, now seemed to feature nearly the entire staff, including Gauthreaux and Silcox, and had become long, desultory conversations that were more like coffeeshop chats between friends. Silcox was also writing articles, work that surely took away from her job as business manager. This is not to be snooty and sniff that “the help” had no place at the creative table, but anyone who has actually worked at an office knows that matters like accounting and appointments constitute immensely complicated, demanding work. They are not side gigs, ancillary to workplaces: they are integral to how a place is run.

Meanwhile, the board, with Rennix as the president, functioned less as a board (minutes were never taken, and meetings were sporadic) and more as what Bee called a “writing collective.” Critical matters like hiring and firing processes were considered on an ad hoc basis, leading to residual conflicts that were not adequately resolved, and resentments and structural problems stayed like lava bubbling underneath.

In Greek mythology, a chimera is a monster with the head of a lion, the middle of a goat, and the end of a dragon. Current Affairs was chimerical in its own way, borrowing bits and pieces from various kinds of structures but never quite gelling into a recognisable shape. It is crucial to understand this part of the story, even if it is about non-editorial issues, because its staff structure—or, rather, the lack thereof—was part of the problem of formlessness at Current Affairs. In “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” Jo Freeman writes about how the seemingly radical idea of informal power structures occludes the critical fact that power is still always at play. An unstructured organisation is not a liberated, radical organisation: it is simply an entity that will cease to function properly at some point. Accountability and delegation are anathema to too many on the left but without them, all you get are long-suppressed tensions that eventually erupt at inopportune times.

Which brings us back to the role of Allegra Silcox. A key point made in the August 18 letter was that Silcox “was even hired with the explicit instruction to help shepherd the magazine through the process of creating a more democratic workspace, in alignment with our socialist values.” This is untrue: Silcox applied for a position that did not mention any kind of restructuring, as is evident from the job description which asked for someone “to focus on managing and expanding magazine circulation and podcast listenership, overseeing financial performance and creating sales strategy, managing product sales and fulfillment, promotion and events, finding and arranging media appearances for Current Affairs writers, and finding new opportunities for our organization to develop and thrive.” All very standard for a business manager, not a labour organiser.15

Silcox had no experience in organising according to “socialist values”: her background was entirely in the for-profit sector, having worked previously for a software company that she has now returned to as a Senior Product Marketing Manager (a position that has nothing to do with organising and everything to do with marketing). If Current Affairs had wanted an organiser to help create a co-op or a union, they would have looked for someone with relevant experience. In fairness, the organisation was also in a moment of much needed transition from an informally run and built organisation to one with a more tangible and workable structure. The lines between fixing internal systems to create a smoother operation and considering how the organisation structure itself needed to be overhauled appear to have blurred, with little direction from an editor in chief and board (which included the managing editor, Gold). As is clear from Zoom recordings of various meetings—including the first one where she presented on the different structures available to Current Affairs—Silcox had to teach herself, from scratch, about the differences between, say, an LLC and a C-Corp. At several points, when asked for clarifications, she notes that she will have to “put a pin in it” and “circle back” (typical corporate-speak) and struggles to explain facts that she has not fully grasped.

Judging from the many pieces of correspondence and recordings of meetings, Silcox was out of her element in a non-corporate structure. At the same time, she also operated in ways that were antithetical to the interests of a small operation like Current Affairs: she was over-eager to spend the organisation’s money, dwelt endlessly on minor matters that were either not within her purview or should have been shelved for later, and created increasingly elaborate sets of procedures and bylaws that seem unduly complicated and labyrinthine (a key method by which corporations exert control is to develop impenetrable sets of regulations that have to be translated by teams of very expensive lawyers). Corporations give themselves the aura of being brutally efficient machines precisely by developing endless systems that are all about creating endless systems: this is also why so many suffer from bloat. As is plain from her presentations and records, Silcox’s strategy for creating a more functional workplace was to throw money around and hire people she liked.

Even by her own calculations, presented at the retreat, revenue was down during her tenure, as were subscriptions. The magazine saw an immense spike in the latter in February of 2019, when Robinson lost his column at The Guardian for his tweet criticising the U.S.’s military support for Israel and readers rallied in support, but beyond that the numbers remained stagnant.

As business manager, Silcox oversaw the hiring of Kate Gauthreaux in May 2020, whom she then had to supervise. In her notes after the interview, Silcox wrote that she made it clear to Gauthreaux that their responsibilities would include “managing reader email, orders, and distribution” and that “while all our staff get opportunities to contribute to the magazine and podcast where appropriate, this role is for admin work that we absolutely need to get done! I want to make sure the expectations for the role are clear (we got lots of applicants who appeared to be looking for an editor position!).” But it became apparent that Gauthreaux was not a good fit, often lagging behind in matters like mailing packages, according to Robinson. While I was definitely not there to confirm this, I can note that Gauthreaux has publicly complained that their (Gauthreaux’s chosen pronoun) job was boring and that all they had to do was answer emails. Given that they were hired as an administrative assistant, it seems that Gauthreaux did not quite grasp the point of their job. They also complained that Robinson had not been enough of a friend to them in the workplace, noting a day when they cried at the office and only got immediate comfort from Silcox. (Gauthreaux did in fact get their emotional needs met at the office that day, which seems to be the most important point.)

Clearly, Gauthreaux mistook the office for something else. In fact, while they suggested, after August 2021, that the job was not ideal for them, they had all along been eager to keep it and expressed their concern about losing the job to Silcox, leading Silcox to reassure them that they would never be fired, according to Robinson (Silcox has not responded to my request for an interview). Robinson took issue with Silcox having made such a promise, and noted it in his email to her when he asked for her resignation. Eventually, a little before the retreat, Silcox devised a plan that would phase Gauthreaux out from under her supervision and, instead, place them directly under Robinson as a “Creative Director,” a nebulously defined position at best for which he would have to train them. Silcox and Gauthreaux presented this idea to Robinson: Gauthreaux would learn all about web and graphic design and meet with Robinson once a week to absorb his knowledge of design and also help him prepare layouts and photo shoots (thus giving him even more work in an already strained position). Robinson agreed, on the condition that Gauthreaux enrol in classes in Graphic Design, to which the two staffers agreed provided that Current Affairs paid for this education. Silcox also raised the matter of turning the magazine into an entity that could be sold for profit, something that went against its founding ethic: this would be one of the sparks that ignited the eventual blowup at Current Affairs. She and Gauthreaux also told Robinson that he needed to agree to the changes before the retreat, in order to fast-track the changes, and that his refusal to do so might well result in a mass of rage-quitting.

A major issue at the magazine had been the sense among non-board members that the division of labour and the degree of presumed oversight seemed disproportionate. The concern expressed was that the in-office staff put in a lot of labour into the magazine without a clear sense of how much power the board (a nebulous entity whose members also wrote for the magazine, and that also consisted of their managing editor and editor in chief) had over them. While this was not entirely an unjustified concern, Silcox’s solution was to get rid of the board entirely and hand over control to the staff—an idea that she raised from the beginning of her tenure and which now concerned Robinson a great deal because by then, he had already clashed with Silcox (and Gauthreaux) over the hiring of Sánchez. He also felt that neither she nor Gauthreaux were doing their jobs, and increasingly felt stymied by them both—especially after being told he needed to agree to the proposal about revamping the structure of the organisation.

Robinson emailed Rennix, Abraham, Nimni, and Bee on August 6, before the retreat, about his concerns with several matters, including his sense that he was being forced into positions he did not want to take. He brought up the issue of Silcox’s desire to get rid of the board and said he had since changed his mind about the overhaul (he had originally thought this a good idea): “The reason being: I chose the people who currently serve on the board to be part of Current Affairs because they are the people I most trust in the world to exercise sound judgment and safeguard the institution. I don’t want to own Current Affairs myself. I don’t even think Current Affairs should be owned. I also think some entity needs to be able to fire me if I get out of hand. I believe that the current board members are exactly the people I trust to be the ultimate stewards of this institution. I do not have confidence in the present full-time staff to govern the institution in accordance with the values I think Current Affairs ought to hold…I would ask you to consider not surrendering your authority when you are asked to do so, and not expanding the board without a thorough screening of new additions to ensure that they are capable of being honest and mature.”

In their responses, board members (Rennix, Abraham, and Bee) agreed with Robinson. In an email affirming that she thought the Silcox plan was not advisable, Bee said she would give her proxy to Nimni, even as she supported Sánchez: “You deserve to be happy at work as much as your full-time colleagues, and Lily deserves a chance to prove herself before being rejected. As for tomorrow, Oren still has my proxy… I trust his instincts and yours to not rubber-stamp Allegra’s restructuring plan without the in-depth, collective discussion that is warranted. You have worked very hard to create a beautiful magazine and I will forever be grateful to you for allowing me to write for it, and then become a part of it. I am committed–especially post September 15!–to serve Current Affairs well, in whatever capacity ultimately makes the most sense.” It was condescending to say that Sánchez still had to prove herself despite having been chosen out of 153 national candidates after a gruelling hiring process, but Bee’s response provides more context to what happened.

Later, during the virtual August retreat, Silcox brought up the plan to transition Gauthreaux into “Creative Director” to the board. Who would do the work that Gauthreaux had been hired to do? A new person, to be hired by Current Affairs. What was the rationale for Gauthreaux to leave a job for which they had been hired? According to Silcox, “Kate would be long-term happier and produce more value to Current Affairs if they were in a creative role” and that “right now Kate’s time is split among too many tasks.” Silcox was effectively saying that Gauthreaux’s job—the one they were enthusiastically hired to do by Silcox, who had also cautioned Gauthreaux about the importance of remaining dedicated to their administrative responsibilities—was taking time away from their being able to do more “creative” work like give ideas for photo shoots (something that was not part of their job description, or required). When Robinson asked how it would be possible to fund all of this, given that web traffic was down and subscriber growth had flattened, Silcox responded, in essence, that the magazine was already spending about $2,000 a month on other positions.16 Silcox added that, “From Kate’s career perspective it’s another line on their resume even if we don’t have a creative director position next year.” In other words, Gauthreaux’s Current Affairs job would now exist primarily to train them for another job.17 All of this reinforces the fact that the lack of structure led to the belief that Current Affairs was a community and a group of friends, rather than a business.

A little later in the retreat, Silcox was evasive when questioned directly by Robinson, who felt that she was hiding her original plans. He asked her point-blank whether the matter of eradicating the board was or was not on the table, a question that Silcox attempted to deflect, but to which she eventually responded by admitting “that alternative was still on the table.” Silcox also wanted to change the magazine’s mission statement, something that was inexplicable to Robinson.

Robinson, beginning to feel that the magazine’s structure could be changed without due process by a business manager who evaded questions and who, he felt, was too often painting him into corners about staffing decisions (like the one about Gauthreaux) and opposing him on crucial hiring matters, and that he had little support in the physical office, sent out his emails.

The “Firings”

On August 8, a day after the Current Affairs virtual retreat, Robinson, feeling frustrated that the magazine was being pulled in a direction that he felt was antithetical to its original mission, sent emails asking three full-time staff for their resignations: Gold, Silcox, and Gauthreaux. He also wrote to McCrea that she was no longer in charge of the podcast but could continue at the magazine as a contributing editor. He wrote to Adrian Rennix, the board president, that they (Rennix’s chosen pronoun) should step down. In each letter to the staff members, he outlined the reasons why he was asking them to resign (in the case of Gauthreaux, incompetence, Silcox because she had failed to raise subscriptions and circulations and was trying to change the fundamental nature of the magazine, Gold because he felt that she hated her job managing writers and work, and McCrea because the podcast was faltering).

Understandably, all of this took everyone by surprise and matters exploded on several fronts. Robinson would go on to retract much of what he initially said to Gold in a letter dated August 9—she selectively quoted from it, and few in the press ever bothered to read or discuss it in its entirety or to reference the other letters he wrote to the others, or the plan for restructuring that he sent on the same day to the board (along with an apology). Knowing that they could not be fired, the staff and Rennix refused to resign, as was their right. The board then asked the staff to propose their own plan for what they would like to see happen (which could have included firing Robinson and taking over the magazine). The board also declared a hiatus through the end of September, and all the staff remained on payroll.

All the hiatus meant, for the staff, was a month-long opportunity to begin a public campaign of lies and dissimulations against Robinson and the magazine. They released the open letter on August 18, and claimed that Nathan J. Robinson had “unilaterally fired most of the workforce to avoid an organizational restructuring that would limit his personal power. Yes, we were fired by the editor-in-chief of a socialist magazine for trying to start a worker co-op.” None of this was true, and they already knew that negotiations were underfoot for a substantial payout.

The word “fired” was used twice in the body of the statement but clarified in a footnote: “Nathan technically asked most staff members to resign…”. [emphasis mine] The letter also stated, “He has effectively fired us for organizing for better work conditions.” [emphasis mine] Lyta Gold, managing editor at Current Affairs made this announcement on Twitter: “I am grieved to tell you that @nathanjrobinson has effectively fired me & most of the @curaffairs staff because we were trying to organize into a worker’s co-op.”[emphasis mine] The dance between “effectively fired,” “fired,” and “technically” implied that all the employees had been fired. Gold made much of their supposedly precarious situation, a matter that many would be understandably sympathetic to during an ongoing pandemic. She asked everyone to contribute directly, saying that “the employees also have a cashapp for donations since we’re all so suddenly out of work & may or may not be able to return to the magazine.”18

For many months, Lyta Gold’s Twitter name was “lyta gold, fired for doing socialism,” driving home the idea that she and the others had been fired for daring to try to execute a socialist re-organising.

lyta gold, fired for doing socialism

The letter carefully avoided saying that they had no idea about how they would support themselves in the coming months: “may or may not be able to return” implied as much. In fact, unknown to readers and supporters, there was already certainty about generous severances and certainty about the inability of anyone to fire them (and that they had not been fired): the discussions were about how much severance. On August 11, the staff, via Lyta Gold, wrote an email to the board to say they did not want to return and said that while a year’s severance seemed most fair to them, they knew it might be impossible. Rennix at first floated the idea that Current Affairs should be dissolved and its “assets” distributed to the workers—they and the staff were surprised to hear that no such “assets” existed.19

In a response dated August 13, Robinson, by now massively regretful and apologetic for how he had responded, heartily agreed with the idea of a year’s severance and also went beyond their proposal with a larger sum amounting to $234,352. There is no indication, in either the correspondence or even the statements by the department staff or the board, that he resisted any of the proposals. Since it was unlikely the magazine could pay out such an enormous sum, he said he would pay for the difference out of his own pocket, by any means possible—even if it meant paying in instalments. Eventually, the board agreed to the staff’s proposal for severances. In the end, including August and September payrolls, the magazine paid out $76,014, divided among seven people . This amounted to five months’ salary for most (and as we’ve seen, money was given out to people who were not even part of the staff).

It cannot be denied that Robinson acted intemperately and without thinking about many of the consequences of his actions and the effects on people—and that he realised this almost immediately. By August 9, within twenty-four hours of having sent out the initial emails, he issued several apologies for his actions. It also cannot be denied that, contrary to the impression conveyed by the departing staff members, Robinson and the magazine almost immediately began working hard behind the scenes to come to an agreement that would be satisfactory to the now departing staff. Between August 9 and August 18, there were several emails and zoom meetings to decide what would happen. Robinson never resisted any of the staff’s demands, and in fact offered them more than they asked for (though it was not in his power to do that, and the board had control and did not accept his offer of a large sum to be paid out over a one-year instalment). The board asked the staff what they wanted, and they said they wanted to leave and get money in a lump sum, rather than in instalments.

By August 18, staff (who knew they had not been fired, could not be fired, and remained on the payroll through September) were well aware of their next steps, that they would be able to get a generous severance (which eventually amounted to five months’ salary), having received an assurance in writing from Robinson himself. Yet their August 18 letter and the CashApp plea gave the impression they had been fired and were “so suddenly out of work.”

These central points—that no one could actually be arbitrarily fired by the editor in chief (a policy to that effect had been in place before Silcox’s arrival), that they all remained on the payroll, and that everyone was aware of this—were quietly ignored, lied about, or erased in the heat of a Twitter wave of misinformation. To clarify that no one was fired because no one could be fired is not a mere quibble over semantics. Let us consider the nature of arbitrary firings, and what kinds of workplaces allow them to flourish. Twitter’s new boss Elon Musk first fired 50% of its workforce, laid off over 4,400 contractual workers, and then sacked workers who had been sounding off about him on internal company chats. At Twitter, the employees had no built in protections such as those at Current Affairs: if there were such, Musk’s employees would have simply refused to leave their jobs and matters today would be vastly different. These are not trivial points. It matters whether or not a workplace protects its workers and to ignore such protections where they exist is to ignore and disrespect the process by which such labour practices have been put into place, to ignore the force and effectiveness of left labour organising that has taken centuries to get us to this place.

THE FIRE SALE

In the end, departing staff and others received payments amounting to about five months of salary for full time staff.

Of these people, only three were full-time: Gold, Silcox, and Gauthreaux. McCrea was a freelancer as was podcast editor Dan Thorn. Sam DeLucia, who was given a month’s salary, had agreed to take on a part-time administrator job after the fracas but then never responded to Robinson’s subsequent emails and never worked. Cate Root was paid for five months like the others, for a job she never even started. It was a massive amount for a small magazine that depends entirely on subscriptions and donations. And, notably, it departs completely from general practice, which is not only to pay less than five months’ severance but never to pay severance to freelancers—let alone severance to freelancers who have not done any work. The more typical severance is “one to two weeks for each year of employment.” Elon Musk promised former Twitter staffers three months’ severance, but has yet to honour the commitment to most of them.) Current Affairs is an infinitely smaller organisation. Despite this, as we know, Gauthreaux would tweet that no one except Robinson got any money.

The impression given, on social media and in news reports, by former staff and their supporters, is that the “workers” banded together to force the boss into giving them any money. But a workers’ struggle, to be defined as such, necessitates that all the workers at least be aware of the fight on their behalf. At no point did Gold and the others who supposedly led the revolt ever contact writers and illustrators to let them know that they were engaged in an organising struggle (I should know, since I’m also a freelance writer at the magazine and was never told about any organising). It was clear from Dan Thorn’s tweets on August 18 and then September 24, that he had no idea he was going to get severance pay, and that he had not been part of any negotiations.

This raises questions: How was the amount calculated, and in what sense was this a “severance?” What was the real purpose of the financial demand if the beneficiaries of this settlement included people who were not yet working at the magazine (Root, DeLucia), were part-time and freelance (McCrea, Thorn, DeLucia), who had not even been asked to leave at all (Root, Thorn, DeLucia, McCrea) and who had been asked to return to the magazine, if in a different capacity (Gold, McCrea), and who did not know that they were among the workers to get a payout (Thorn)? In a literal sense, Thorn found himself without a regular freelance job without warning, his claims of solidarity notwithstanding.20

The calculations were made with this question in mind, How much money can Current Affairs give them without going bankrupt or violating our legal duty? I can testify, based on my conversations with those concerned, that this was in fact part of the negotiations. The departing staff members were not trying to redistribute the wealth and resources of a massively rich owner and his family among oppressed workers: they were trying to decimate an independent magazine funded by subscribers.21

Paying out amounts only to those directly affected (Gold, Gauthreaux, Silcox, and McCrea) would not have been a large enough number ($54,936)—and this, we can surmise, is how and why it was decided that Root, Thorn, and DeLucia would also receive money. Looking at the amounts given out to people who literally did not work there or who had no idea there was some revolutionary struggle being fought on their behalf, we can only conclude that the last three were only allocated their money to add to the burden of the eventual settlement. The money given out was not an attempt at justice but a giant fire sale.

When the staff realised that they could not do what they originally intended—dissolve Current Affairs and distribute its (non-existent) assets among themselves—they took what they could and then continued to work at destroying the magazine. Attempts to discredit the remaining employee at the magazine would be part of that strategy and they launched a Tsunami of Spite on all fronts.

RACE, AND A TSUNAMI OF SPITE

Over the last nineteen months, the former staff and its supporters have embarked on several simultaneous campaigns of misinformation and called for more bullying of Robinson. Perhaps the worst has been their attempt—in which they were joined by board members Vanessa Bee and Adrian Rennix—to paint Lily Sánchez, then the new online editor (now the managing editor as well) as a scab who crossed a picket line (we will note, again, that there had been no organising). They have portrayed her as less qualified than the white woman who did not get the job, Sam DeLucia, and as someone who was only hired because she is a woman of colour.

This is a set of lies.

On August 20, frustrated by what he saw as the deluge of misinformation being spun out by the departing staff, Robinson published a lengthy statement refuting their charges. In it, he pointed out that he had grown to distrust Silcox in large part because of her resistance to hiring a highly qualified person of colour. To prove this, he published an excerpt from an internal Slack conversation.

In his public statement, Robinson also made several other points about what had transpired, pointing to what had overtaken the magazine: “There was a serious “structurelessness” problem, with people having unclear roles and unclear titles. There was a lack of any supervision of work, resulting in work not getting done. Current Affairs had become more of a club of friends than a fighting socialist magazine effecting change in the world.” He also detailed the problems with money (the podcast, the magazine, and the website had all been trailing in revenue).

In response to Robinson, Adrian Rennix posted a public statement that spread the canard that Sánchez was an unqualified candidate.

The statement completely ignored, in the spirit of High Paltering, all the other issues Robinson raised, including the poor performance of Rennix’s former colleagues (Rennix also neglects to mention that they were board president, simply and conveniently describing the board as “a mostly ceremonial body”).

Rennix writes, “Early in the hiring process, Nathan identified a candidate he himself preferred, who was one of the women of color. He offered her detailed advice about her editing test by email in advance of her submission. When other staff members saw that these emails had only been sent to one candidate but not the other three (including the other woman of color), they felt that this had been unfair; Nathan’s advice also resulted in a submission that, while highly promising, was significantly different in format from the other editing tests and hard to compare to the other frontrunners. As a result, when the final decision came down to two candidates — one of whom was Nathan’s preferred candidate — and the staff was divided between them, some staff members asked that an additional editing test be administered to both candidates, without any additional advice, in order to ensure fairness.”

In fact, the instructions sent out to the job candidates about their edit test assignments clearly stated that they should write to jobs@currentaffairs.org for any clarifications and explicitly stated, Don’t be afraid to be bold…This is just an exercise so you should let your imagination run free.” [emphasis theirs].

Sánchez wrote to the email for further clarification about how far she could let her “imagination run free” in interpreting the assignment. At this time, all these emails and any subsequent correspondence could be and were seen by all members of the committee: Silcox had installed Hiver specifically for this purpose and had in fact previously responded to Sánchez, in response to a procedural question. Robinson responded to Sánchez, in an email seen by everyone else, echoing the official words, “And to reiterate, I would encourage you to be bold and have fun with it.”

When Sánchez eventually wrote something that was “significantly different in format,” she was doing what all candidates had been encouraged to do, and the correspondence between her and Robinson was within the parameters of the instructions and in full view of all concerned. There was a second edit test administered, but Rennix, in their carefully worded revisionist history, leaves out the fact that this was procedural: they had two front-runners and this test was to choose between them, not because the process had been corrupted. Rennix is correct that Robinson only emailed Sánchez and not the other three but leaves out vital information: Robinson had not sent unsolicited advice to Sanchez but rather had answered her question. The other candidates had not asked questions.

Robinson was also charged with having “identified a candidate he himself preferred” — words clearly echoing Gold’s words. But who on a job hiring committee does not have preferences? It’s taken for granted that every member of a search committee will develop a preference for one or more candidates: the whole point of having committees and not individuals choose new employees is to ensure that the person fits most people’s sense of their compatibility with both the workplace and the people in it. Why was it okay for Silcox to so plainly state that she wanted a workaround to choose the white candidate, without that being identified as bias? How was the later hiring of DeLucia as a part-time freelance editor, to keep her around until she could be shoe-horned into a permanent position that looked a lot like the one she did not get in the first place “because we love her,” not in fact a show of bias?

Eventually, as even Rennix’s narrative points out, Sánchez was voted in by a majority (this included the board’s Vanessa Bee who gave her proxy vote to Oren Nimni; Gauthreaux was a holdout). However, even in making this admission, Rennix suggests that Sánchez was inauthentically socialist: “a woman of color from a professional background who had become enthusiastically involved in left organizing” while DeLucia was “a white woman who worked service jobs throughout her adult life and had recently organized her workplace to raise wages for her fellow-workers.” There’s an almost imperceptible rhetorical thumb on the scale here: the professional woman of colour is assumed to be upper class while the white woman is the salty working class Norma Rae figure who has organised her fellow workers. Rennix tilts the narrative to read as one where the woman of colour was simply given the job by dint of her race.

Rennix deliberately erases Sánchez’s work history which is in fact especially relevant to the socialist politics of the magazine: she worked for six years as a paediatrician in a nonprofit clinic, taking care of patients with Medicaid or who were uninsured, and the children she worked with were mostly Black or Latino/a—as was her workplace. But in Rennix’s rendition, she becomes a figure akin to a privileged white saviour lady, choosing to enter left publishing on a lark (she in fact left her more lucrative job prior to joining Current Affairs full time). Rennix also leaves out a crucial fact: that Sanchez has considerable experience with editing and writing while DeLucia, by her own admission, has none. 22

All of this was also a great deal of smoke and mirrors: while Rennix’s words made DeLucia seem like a salty, authentic, working class high school dropout who must have gone straight from a rural shack to work as a coal miner—apparently the only worthy occupation for any socialist editor—she in fact has a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice. And this cannot be emphasised enough, given that Rennix and others have cast Sánchez as the inferior candidate who was only selected because of her ethnic identity: of the two, Sánchez has—in addition to organising work— many years of experience with editing in different contexts, while DeLucia has none.

Yet, Rennix denuded Sánchez of agency and dignity by implying that she couldn’t really have tested so solidly in the lead with only one other candidate in a field of 153 applicants (the number that applied): this was apparently only possible with Robinson’s help.23

A year later, Sánchez would be attacked even more explicitly and publicly, by Bee who placed herself in a conversation between Sánchez and Marge Wu (one of the staff’s most ardent followers and trolls of the magazine) when Wu tweeted that “there was union-busting going on.”

Sánchez, who has long been quiet on the matter, felt compelled to correct Wu:

To this Bee jumped in to respond:

Bee seems to be informing Sánchez of organising efforts that were taking place to the latter’s exclusion—an interesting way to describe“organising” at Current Affairs—and was shockingly cruel towards someone she had known well enough to support.

In such ways, two former members of the board have slyly insinuated that Robinson was not only someone who attempted to break organising attempts at a magazine, but that the sole woman of colour on staff was both an undeserving hire and a scab. Bee’s comment, “You are correct that the staff was seeking to become a workers coop, not a union” is, firstly, a lie since there was no attempt at either and, secondly, stinging in its refusal to acknowledge that Sánchez was hired in a process that included Bee’s support.That such assertions should come from Bee—herself the only woman of colour on the board and someone who writes frequently about the obstacles faced by women of colour—made it easier for white trolls, like Jack Reno Sweeney (the partner of Kate Gauthreaux), to also jump up and call Sánchez’s statement of fact “bootlicking.”24

As for Sánchez staying: she felt no obligation to be in solidarity with a group of people who were clearly burning things down. In correspondence with me, she explained her position: “Since there might be some theoretical leftist expectation that a person in my position would (or ought to have) quit the job out of protest or ‘worker solidarity,’ I will say this: I did not feel it was right to quit my job over a complex conflict among friends and coworkers which was being promoted in public in the most narrow and inflammatory way possible.” She continued, “Since solidarity requires mutual support, I did not understand myself to be in solidarity with workers who…intended for the organization to, well, end, in their own words (“RIP,” a “light going out” and “new projects” being hinted at per the August 18, 2021, statement), and who led me to believe that they were requesting a peaceful ‘hiatus’ but then released a statement that seemed intent on discrediting the online reputation of the organization and the Editor in Chief…”25

In the aftermath of the incident and its blowup on social media, the magazine and its associates (including me) suffered various kinds of blowback.

- The Current Affairs matter is not simply a fight among friends that spilled out: left institutions got involved without getting multiple sides of the story. The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) branch in New Orleans ejected Robinson as a member with a statement that erroneously copied the charge of “union busting.” This was in violation of DSA procedure, because there was no hearing or opportunity to rebut the charges, only a public notification that Robinson was out.26. The International Workers of the World Freelance Journalist Union issued a solidarity letter condemning Robinson’s “authoritarian act” of “retaliatory firings.” By the time October rolled around, the Current Affairs story had cemented itself into a satirical novel that wrote itself: What The Left Is Really Like.

- Over the last nineteen months, Current Affairs and Robinson in particular have been subject to rumour-mongering, innuendo and outright harassment. The consequences are personal but also damaging to a magazine that continues to be pilloried by a small but toxic and vocal group of people who seem to have made it a hobby to harass Current Affairs as much as possible. Scraping the barrel of toxicity, Gauthreaux and her partner have even posted images from Robinson’s Tinder profile, literally mocking every detail, on one occasion posting three times over the course of an hour.

- In August of 2022, when I tweeted that I was working on finishing this piece, Sweeney tweeted that he would, as soon as my piece appeared, make a concerted effort to smear my name—using the name of NAMBLA as a radioactive signal.

It is noteworthy that Sweeney’s response to anything I might write is not some version of, “We will be prepared to dispute her side of the story” but rather, “If she writes this, we will smear her name.” (When I confronted him, he quickly blocked me, like a true bully). Lee Atwater, the infamously vicious Republican strategist whose methods of smearing candidates with everything from insinuations to outright lies, would be proud. In addition, Sweeney (whose tweet was liked by Gold and Gauthreaux) is engaging in exactly the same tactic as the Right vis-a-vis the gay community: he seeks to discredit and besmirch me, an openly queer person, by explicitly linking me to a discourse of child sexual abuse and grooming, using language that has historically been used to demonise and even kill queer people.27 With socialists like these, who needs the right?

PATER MAGAZINA

On the day after he sent his initial emails, Robinson received a call from one of the people affiliated with Current Affairs who told him that he, Robinson, was like a father who had abandoned his family. I believe that this is one reason why, in his initial comments and his first statement, Robinson tried to take on all the blame for what had happened: his sense that he had massively failed in a personal capacity, not just as an editor in chief (in my conversations with him immediately afterwards, he was distraught and regretful). But while he is hardly blameless, it was never true that he alone was the cause of everything that happened. I have returned often, in my mind, to that other person’s formulation of Robinson as an unfit father and the primal scene it evokes, of filial betrayal and a shattering of trust.

To position Robinson as a paternal figure is to turn what happened into a matter of personal relationships alone. It is to erase the fact that what happened was about the lack of structure at a magazine enterprise that included six board members, nearly all of them with law degrees, and a number of full and part-time staff members and freelancers, all adults. The August 18 letter stated, “We, a small staff composed entirely of women and non-binary people, have faithfully worked to make Current Affairs the beautiful, engaging leftist magazine and podcast that it is.” But not all the signatories were on staff, and the sentence implies that Robinson was not staff but a lord and master while leaving out the fact that Gold was a managing editor and on the board of directors. Hurling him out of their group and positioning him as a Bad Boss and quietly raising the matter of gender was, I believe, yet another insidious way to quietly compel people to their side.