Every weekday, I send out what I call the Daily Post: something from my archive of previously published work.1I often refer to this as “today’s DP,” and my friend S. inevitably giggles that they can only think of the term “double penetration”: I aim to provide levity whenever I can. The standard operating procedure for most authors is to only showcase recent work, but I like to remind myself and any aspiring writers that “writing” is a process that takes a lifetime: it’s never done, and you move through various writerly selves and styles over the course of a career. The day you decide that you’ve reached your pinnacle is the day you’ve died as a writer, and it’s a sign that you should move on to something else.

This morning, I thought of this review of Shirley Wins, by Todd Taylor. I wrote it in 2007, and it was my first review as the Books Editor for Windy City Times so, nearly two decades ago. I fell in love with this short novel. Over the years, I’ve reviewed several books but very little fiction—contemporary works began to wear on me, signs of a publishing industry that demands a boring sameness from writers.

What I loved about Shirley Wins was its ability to delve into a tiny slice of life: a woman, Shirley, enters a pumpkin-throwing contest with the help of her granddaughter Rachel and a few other characters. That’s really it, all that happens, but Taylor’s short, deft narrative is able to do a great deal. As I wrote then, “The novel is as much a meditation on the nature and rhythms of work and the patterns through which we get projects done as it is about Shirley’s path to the pumpkin chuck,” and it’s “an account of the unconventional, intimate and sometimes fleeting relationships between people who unite for a common cause.”

I think about Shirley Wins often as I look at new novels, especially the ones from the Big Five Three One (let’s face reality: this is where we’re headed). With notable exceptions—Emma Cline’s masterful The Guest comes to mind, as does Sally Rooney’s Normal People—novels today seem to hew to publishers’ demands that they feature giant, sprawling vistas packed with every possible lesson about What It Means to Be Human. Every work is “magnificent” and “sprawling” and “spellbinding” and “speaks to the question of what it means to be [insert anything here],” ultimately offering “a revelation that is every bit as devastating as it is life-changing.” In each, readers are like visitors on a tour of the Serengeti and the author is the voluble host: Look, a trauma! There, there, do you see? In the trees, right there, where my finger is pointing! And over to your left, everyone, a rare thing indeed: a happy marriage!

The blurbs alone are exhausting and appear to have been created in a factory somewhere, no doubt penned by unpaid interns; the fiction itself leaves you wishing you could just get off the jeep and walk back to the hotel, even it means risking your life among hungry lionesses on the prowl for supper. It doesn’t help that so many novels these days are written like screenplays or treatments for a multi-episode Netflix show, and while reading I can often picture the pitches and I’m reminded of scenes from Robert Altman’s The Player, but with writers selling their books: It’s Tolstoy but without the angst, think Hemingway but with a dollop of Zadie Smith, and for the cast: we’re thinking Lily Rose Depp and Ayo Edebiri, a winning combo. Reading one of these makes me wish I could just read a good old-fashioned nineteenth century novel. Dickens originally wrote his fiction as serialised novels (the Netflix series of the day), but you still can’t help hanging on to every word of Bleak House, from that astonishing first passage to the end.

When people discuss (ironically, perhaps) the Great American Novel they mean a work that somehow crystallises a certain kind of national identity but also something, well, great. And that word is often applied unironically to novels in general, from all over, to mean something magnificent, wide-ranging, packed with human experiences, travels and journeys, explorations both internal and external. Too often, novels today fall under the weight of greatness and you can often tell that the author, at some not always indiscernible point, just gave up and reached into the vast mine of clichés available in recorded literary history. Much of this is because the publishing industry (The One, as previously noted) no longer wants to gamble on something that can’t be turned into a Big Movie, or a Netflix Series. For that you need characters, characters, lots of characters, and action, action, action but also, meaning, meaning, meaning, and at least one death, maybe two but no more, and more meaning just, something… great, you know?

The economics of the publishing industry make very little sense until you realise that the only people actually getting rich off it are a very few top executives, who can make millions while the average starting salary is barely $50,000 (often impossible to live on in, say, New York, where a good segment of the jobs are located). The predominant myth about writing is that writers earn large advances that set them up for lives devoted to writing, and this myth is carefully cultivated by aspiring writers who feel the need to nurture it, despite all signs to the contrary. Over at Esquire Karen Dwyer asks, “So how is it that so many writers seem to be living comfortably?”2Dwyer’s essay deserves a longer, more considered look because it’s so disingenuous and paints an odd and distorted picture of the publishing world. It also reads like a press release for Vanessa Chang’s unpublished (at the time) novel. I’ll have more later. It’s a bewildering question, unrooted in the reality of most working writers but Dwywer only speaks to best-selling authors like Tom Perotta and establishes $300,000 as a baseline for advances when the reality is that most writers are lucky to get $5000 (she waves, vaguely, at this fact, but then returns to conversations with the top-tier authors). Increasingly, the only people who can afford to write are either married to spouses who support them or already have family money. In Dwyer’s world, writers struggling to make ends meet while also trying to keep their writing going…simply don’t exist.

What, you might wonder, does this have anything to do with the massive and needless scope and span of recent novels? There’s the “bang-for-your-buck” theory, that if you’re going to ask someone to put down nearly a quarter of a hundred dollars or more for that flashy new hardbound volume, they should get a vast, sprawling, blistering, spellbinding novel, and all of that at once. There’s the fact that as publishing houses steadily merge into The One, there’s simply less biodiversity and an unwillingness to engage with work that might not fit the template of a “New York Times bestseller.” That phrase is in fact meaningless because the Times’s list is, well, bullshit (the paper has confessed that the choices are editorial and not based on mathematics; authors and publishers can skew the results by buying in bulk). Perception—that cute golden sticker on a book—can alter reality, and so “bestseller” books end up defining trends in fiction. There’s a reason why you won’t read much fiction about immigration that’s any different from the five other books you wearily plodded through, hoping for more than the standard “I am born of wretched people yearning to be free, and now I am happy, or maybe not?” tripe. And, unfortunately, too often, large blocs of readers end up resisting anything that deviates from a template.

And thus is born the “great” novel: that unwieldy, 560-page opus overstuffed with characters and too many plot lines, all meandering to convince you that you are experiencing something close to a transcendental experience, something, well, you know, great. Something that will come soon to a Hulu near you, serialised into a soul-crushing, mind-numbing 10-episode series whose only saving grace is that it might provide employment for an entire group of costume designers and makers and everyone else behind the scenes.

As a lover of Dickens and Austen and several other Dead White People who found their way into and around long, luxuriant novels, I’m the last person to demand an end to such. But it’s time we acknowledged that too many novels today are needlessly long, and that their length is driven by market forces. Can we make space for the Small Novel? Something quieter and more reflective, something that explores relationships and events in depth and detail even as it seems to be about little more than a woman getting ready to hurl a pumpkin as far as she can.

Added: As Jayaprakash Satyamurthy points out, small novels are more the norm for small presses. My essay was meant to reflect the ways in which major publishers determine too much in terms of tastes and what gets published but, to be clear, in line with JS’s point, small and independent publishers have been doing the work of producing more thoughtful work for a long time, even as the mainstream press ignores them.

For more on publishing, see:

Marie Claire Throws Dog Food at Writers

A Portion of the Mind: On Writing and Nobel Prizes

Don’t Share Your Book Proposal

The Corruption of Influence: On Dimes Square, Byline, and the New York Times

Lyrical Doughnuts or, the “I” in Writing

The Publishing World Is Like Fyre Fest

And a host of other essays, found here.

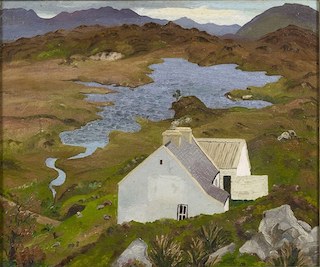

Image: Connemara Landscape, County Galway, Ireland, c.1936, by Cedric Lockwood Morris (UK,1889-1982)

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.