You will always have that experience, and it will always be for the better.

I’ve long advocated paying writers for their work, I’ve admonished writers to not sell their work for free, and I’ve come out and called those who do scabs.

I’ll be returning to this issue, of paying writers, in a new series starting in late spring, but for now I wanted to take up a related matter, of supporting writers who write books by…actually buying their books.

The good news about books is that people are reading more—the pandemic is certainly one reason, but I like to think that there’s more of an appreciation for books and reading overall. Even more surprisingly, people seem to prefer hard copies of books over e-books, for a number of reasons. I’m in love with my Kindle and one of my morning rituals is to peruse the bargains from a list that arrives in my inbox and buy a book or two (99 cents! $2.99!). I love the idea that I’m carrying around untold numbers of books with me in a single device. Several of them, like the Agatha Christies I read at bedtime, are electronic versions of beloved physical copies I had to get rid of when I downsized several years ago (I ripped off and kept the gorgeous covers, and have amorphous plans for using them in some kind of “artwork.”). I also have copies of books on every topic you can imagine, and whether or not I’ll ever get around to reading them…well, let’s just say that, too often, when I try to buy a book, the Kindle bot will cough delicately and remind me that I “already own this book, and would [I] like to read it now?” But, like many readers, I prefer hard copies and won’t even review ebooks: physical books are just easier to navigate and take notes on, despite all the promised advances.

Books can be expensive, although there are several ways to find cheap or free versions. One popular method is to find a pdf that someone has uploaded somewhere. I know from my many years of arguing with people online about the necessity of buying books that there’s a large section of the left which fervently believes that downloading books for free is some kind of insurgent, revolutionary act. At one point, a lefty professor smugly intoned that “writers just want to be read” so he had no problem with anyone reading his book for free. I haven’t kept up with him, and this was several years ago—but I’m guessing that, given the ravages of academia, the dude is now desperately fishing around for work as a “public intellectual” and hopes for a book contract and that people will…buy his book. I, as an actual writer who both wants to be read and relies on writing, not any other day job, as the source of my income, actually need people to not just read me but pay for my work. Tenured professors and even graduate students who have monthly incomes don’t need people to pay for their writing (plus, academia schools you in the idea that writing is not labour but just a love of knowledge, and fighting that central idea is like walking into a temple and arguing against god).

The publishing industry relies on a central myth, that every writer can hope for a $3.75 million dollar contract, the sort bestowed upon Lena Dunham for what turned out to be nothing more than a vaguely interesting diary, interesting mostly because it was written by one Lena Dunham who writes incessantly about being Lena Dunham, something that hordes of people think is a worthwhile pursuit because what Lena Dunham does really, really well is convince people that she’s someone people ought to follow because she’s, well, Lena Dunham. Did her publisher ever recover that massive amount? We may never know—trying to find actual, reliable figures on matters like how much money did this actually make is seen as gauche, as if you were at an elegant dinner party and asked the price of the china, and also like getting a Swiss bank to open up about how much money it has and who its celebrity clients are. People clam up, there are supposedly databases of all sorts, somewhere, they cost a lot of money, and the information is mostly unreliable. My dream is that someday I’ll find the equivalent of a literary Deep Throat, a mysterious shadowy figure half-hidden behind a column in a garage who hands me a slick little thumb drive with all the figures behind every celebrity book deal.

But there are, of course, best-selling authors whose books make their publishers tons of money: Stephen King could publish his grocery list, and it would sell millions of copies (thankfully for us, he does a lot more than that and our world is better off for it), as could Danielle Steele, and a host of other established names. These are the reliable names in publishing, but then there are the strange one-offs, writers like Kristen Roupenian whose dazzlingly mediocre short story “Cat Person” went viral and landed her a $1.2 million advance for a book eventually published in 2019, You Know You Want This. As far as we can tell, it’s not a book that actually sold well but Roupenian is white and pretty, and will no doubt get yet another book deal, if not of similar proportions: let’s not worry about her fate.

The point I’m getting to is this: most, the vast majority of writers don’t see anything like this kind of money, but too many of them also hope to win the lottery. In general, an advance is much, much smaller than the millions you read about, about $10,000 on average. That amount is usually paid in instalments, and agents will also need their cuts (this is normal and also pays for labour, so simmer down before you begin expressing outrage). The reality about publishing is that most writers struggle to sell their books and rely on day jobs of some sort to pay the bills. Most writers really, really need you to buy their books—illegal downloads don’t count as sales and every time you rip off a publisher, you’re making it less possible for that writer to get another book deal based on past sales. Yes, yes, I have no doubt that many, including my fellow writers, will point to several complications in all this, but my central point stands: buy those books.

There might be exceptions, of course. Academic presses are subsidised by their institutions, and generally pay their authors little or nothing (most are academics with paying jobs). Academic journals are part of a particularly exploitative economy, receiving state subsidies which fund the research they then place behind very expensive paywalls. If a pdf of an academic book should land in your inbox, you should ask yourself: will it hurt the author who hasn’t been paid anyway, or the press which is probably selling it for far too much, sometimes over $100, because they rely on university libraries to do the buying (a rule for my upcoming books and research podcast is that I won’t look at academic press products above a certain price). It’s worth keeping in mind that some academic presses have trade divisions, though, and you should check on that when you see an imprint’s publications.

The same is true of vanity press projects: if an author is actually paying a press to publish their work, why worry about whether or not you can help them recover that cost? Let them distribute it for free. Many indie or indie-seeming presses don’t pay at all. Verso, which seems to own a large catalogue of theory and philosophy, does not pay its authors and appears to operate much like an academic press, so treat them the same way. Long-dead authors? I mean, look, go ahead, but remember that a good press will issue a reliable version of, say, Jane Austen’s Emma, along with accompanying historical material and commentaries that represent a degree of unspoken labour. If you can’t afford to buy a book— I’m often in that situation—ask your local library to acquire a copy, along with the ebook version if available.* Still not sure if the book you want is from a publisher that actually pays its writers? Become a more engaged reader: write and ask them. If more readers became actively curious about the material realities of publishing, the world would be a better place for writers.

Most of all, Dear Reader: think about books as the product of intensive labour you can’t always see. Might you buy a book and then find you hate it? Sure, but that’s not relevant to the question of whether or not you should buy it. A book is often years of work, whether that work involves crafting finely-tuned stories and characters or chronicling a labour movement, work that involves talking to often hundreds of people over the course of months. A book is not a latte you return because it’s too bitter or not bitter enough: it’s a commitment you make to another human being to, for a while, follow the trajectory of their thoughts and ideas, to delve into the worlds they evoke, fictional or not, to see where their minds might take you. You wouldn’t ask for your money back from the pilot of a plane that takes you to a vacation spot suddenly battered by an unexpected summer storm. Buy a book, read it, and consider that even if you end up hating it, something has immeasurably shifted in your intellectual DNA, you have learnt something new, you’ve contested or adopted new ideas. You will always have that experience, and it will always be for the better.

Buy that book.

*Many thanks to @muchlibrary on Twitter for reminding me of this.

This piece was edited to include a sentence about Verso.

Yasmin Nair lives in Chicago, which was once a centre of the publishing world—although no one remembers that now—and is working on her book Strange Love: How Social Justice Was Invented and Why It Needs to Die. She knows you’ll buy a copy when it emerges. In the meantime, you can support her with a subscription or a donation.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

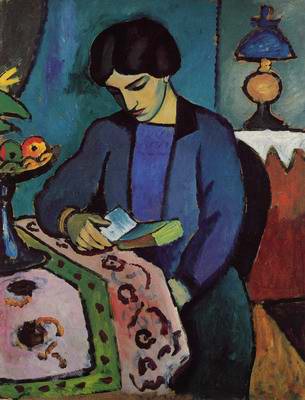

Image: Blue Girl Reading

Auguste Macke (Germany, 1887-1914)