Excerpt: What kind of culinary omerta survives in Hyde Park to keep its restaurants at such a depth of mediocrity?

Note: This is not a restaurant review.

I have deliberately chosen not to name independent restaurants, except for a few exceptions, not out of any sentimental love for “mom and pop” enterprises (which aren’t required to unionise, given their size, and whose owners can be racist and/or sexist — like Trushar Patel of Rajun Cajun–* with impunity since they’re often the only available places in small areas) but because I’m less sympathetic to corporations.

The fact that a place makes one dish very well does not imply praise for everything else available there.

I’m not a food snob — I think that a $3 hot dog should be made and presented with as much care as a dish involving ingredients sourced from Italy and sold for much more. The point about food is not what you make, but how you make it.

UPDATE: On June 30, A10 announced that it will be closing. 2022 Update; Several other places have also closed, like Bridgeport Coffee. Treasure Island has closed (all over Chicago) and half its old space is now taken up by Trader Joe’s.

The woman was ahead of me at the hot bar of Treasure Island, a Hyde Park grocery store, and was taking her time, casting a suspicious eye on all the food sitting under heat lamps in steel tubs. Nothing, not one of the offerings, could make her happy. The clerk behind the counter had the carefully composed look of the long-suffering. Looking sternly down and then up at him, she pointed to a dish and asked, “And what is that?” “Dirty Rice,” was the response. “That’s not dirty rice. It’s nothing like dirty rice.” The clerk remained silent, not wanting to get into an argument the point of which would have been above his pay grade. Finally, the woman spoke again, imperiously, “Well, okay, give me half a pound of the chicken. And throw in some of that alleged dirty rice.”

Alleged. I was reminded of that joke at the start of Annie Hall, about life: two elderly women are complaining. One says, “Boy, the food at this place is really terrible,” to which the other responds, “Yeah, I know, and such small portions.” Yet, I understood the woman’s use of the word alleged, perfect for Hyde Park food which takes on the names of dishes that, elsewhere, evoke taste and pleasure (“purported” would have been the correct term, but alleged has the right sting). Here, everything is merely alleged, the dish in name only.

Until I moved to Hyde Park, my philosophy about food from a restaurant or any take-out establishment matched Jerry Seinfeld’s, on fruit. To borrow from him: I don’t return food. Food’s a gamble. If I’m not happy with a dish, I shrug it off to the fact that the cook’s style and culinary profile are not in alignment with mine; our tastes are different. I simply resolve never to return. But it’s different in Hyde Park, which has driven me to the edge with food that ranges from indifferently made to plain horrible. I’ve returned dishes to various places, including uncooked potatoes (how hard is it to cook potatoes?), a Thai dish whose grey mushiness horrified me so much I’ve even forgotten its name (I refuse to look at the menu for fear of being re-traumatised), fish cakes that were a strange, violent shade of red with a texture that made a sponge seem like a delicious teatime treat in comparison.

None of this makes sense. Hyde Park, dominated and arguably ruled by the University of Chicago, is on the south side, home to an African American population with deep roots here. It’s considered one of the most diverse neighbourhoods in a city that has elsewhere refined racial and ethnic segregation to a fine art, and it is home to a university with a significant international student population: twenty-five percent of the student body is of non-American origin. This is a university that offers courses in languages like Hindi, Akkadian, and Old Egyptian, and houses an entire department of Slavic languages and literatures. If a new country were to form itself somewhere between, say, Moldova and Ukraine, it would bankroll a cadre of fresh-faced young graduate students to study the finer points of neoliberalism, which was birthed in the august, fake-Oxbridge halls of the University of Chicago. One of the annoying aspects of living here is that I can’t be rude to someone in Syriac because the recipient is likely to respond with much more colourful insults, and with greater fluency. Given all this, I expected something like what I was used to in Uptown, where there is a world of foods to be found.

Surely, it is impossible for so many restaurants in such a small parcel of land filled with people of literally every race, ethnicity, and national origin to have formed a food wasteland without some kind of conspiracy among them. What kind of culinary omerta survives in Hyde Park to keep its restaurants at such a depth of mediocrity?

A major reason is the neighbourhood’s isolation from Chicago. Hyde Park is effectively landlocked from the city, whose other neighbourhoods are in physical proximity to each other. To leave Hyde Park, you have to drive or take a bus or two or a bus and a train or more, depending on where you live; you can’t just walk out of the neighbourhood to eat elsewhere. Restaurant owners know that, and most of them close at 9 p.m., which is like an informal dining curfew hour here. By 8:30, there are people scurrying around desperately trying to find food to eat. If you have been so careless as to forget to plan your meals ahead as suburbanites must, you will be like that hapless gent I ran into one night, frantically looking for a meal somewhere, anywhere because everything was just about to close.

For millennia, people around the world have carefully honed and perfected their cuisines. Hyde Park is where all of those traditions come to die.

Gloop is the word that best describes Hyde Park food; its restaurants suffer from a fear of texture. Where there is texture, it is evil and deceptive, the result of an accident. One might bite into what looks like a lovely crispy bit in the au gratin at the Whole Foods hot bar, which should, after all, have lovely, crispy bits. And it will turn out to be just a part that has been exposed to the air and is vile: not crisp but crusty from sitting around for too long. A friend ordered a pizza from a place famed here for such, and the middle was odd, soggy and strange, like a mattress gone soft. The pizza at Giordano’s, one of the founts of Chicago’s famous deep dish pizza, here looks (and, I think, tastes) like a tiny child’s wading pool, a ring of dough filled with a gloopy sauce that has no flavour, no hint of herbs or garlic.

There is nothing local restaurants — and we must use the term loosely — will not massacre in their journey towards the bottom of mediocrity. Consider, for instance, Pad Thai, perhaps the most ubiquitous and yet most charming and satisfying of basic dishes you could have in an average Thai restaurant. It’s a dish snobs avoid as if it were the McNuggets of Thai cuisine ( it’s not that Thai in its origins) but it’s what you reach for when you’re not feeling adventurous and just want a satisfying mix of carbs, veggies, and proteins: slightly chewy rice noodles in a delicately assertive sauce, the texture beautifully complemented by a generous sprinkling of scallions, bean sprouts, fried garlic chips, peanuts and cilantro on top. It’s quintessentially Thai in its ability to combine several textures and flavours into a single dish.

In Hyde Park? Order this at any of the allegedly Thai restaurants in the neighbourhood and what you get is a mess of weirdly sweet and deeply entangled noodles into which no one will have bothered to incorporate more than some indifferent brown substance which gives it that authentically Hyde Park look, a tired tint of deep sadness, the harbinger of doom, the look of death. There might be vegetables and meat in there, but they will have acquired the same patina as the noodles, which makes them hard to find. There are never any toppings and apparently no one here has even heard of bean sprouts, which lend a cool and crunchy freshness to the dish — in Thai restaurants, in other neighbourhoods.

No single Thai restaurant does every dish even moderately well, and there’s never a guarantee that a dish done well one day will taste the same on another. The Pad See Ew might be not-bad in one place, but its massaman tastes, well, it just tastes yellow (in Hyde Park, “not bad” is the highest level, the equivalent of a Michelin star). The green curry is gloopy at one place, okay in another. To construct a good Thai meal, you have to order different items from three different restaurants. It’s a meaning of à la carte the French never intended.

Other examples abound. That alleged “kabob sandwich” at the “Middle Eastern” restaurant. It hung from my hands, limp like a dying bird, the icy-cold pita (how much effort is it to slap that on a griddle?) already moistening from the warmer contents inside. The meat was dry, barely seasoned, lumpy in shape, and tasted much like what I imagine regurgitated, masticated food from the mouths of mother birds feeding their young must taste like.

The sandwiches at a place where the bread is really good, and the fillings are not bad. But: the latter are never distributed evenly. You inevitably end up devouring all the protein in one half and by the time you get to the second half, eagerly, you discover that all you’ve got is a lot of lettuce and tomato. Every time I ordered one of these “sandwiches,” I’d try to guess which side the meat might have sunk to and eat accordingly, but I was wrong every time. I finally gave up.

The bakery, whose pastry maker is a Person of Great Genius, and whose creations are truly wondrous, but where the coffee tastes like water flavoured with coffee, and where it can take an hour to get a lox sandwich. And where no one seems to think that this might be a problem (and where the taste of the sandwich depends entirely on the person making it, and their mood).

Anything at the Whole Foods hot bar. This place is worth noting because the university, located in the south side’s food desert, chose the chain over cheaper (and arguably more diverse in produce) grocery stores as part of its constant attempt to upscale and become a satellite of the south loop. Whole Foods hot bar items tend to be expensive, but they’re fairly good and even delicious (the Lincoln Park branch offers some damn fine brisket). But the one here is much smaller, tucked into the bottom of the dazzlingly new City Hyde Park apartment complex, and its blazing contempt for (mostly Black) southsiders is revealed in its presentation of the food which it can’t even be bothered to label correctly, if at all. It does not offer many of the same (and presumably more labour-intensive) items as other branches, and even the common ones, like the mac and cheese, are made differently here (read: worse). In the south loop branch, the dish is delicious, creamy and rich. The version you get here is greasy, slightly orange, runny, and made with inferior, gritty cheese.

Nostalgia abounds when it comes to restaurants here. Ribs and Bibs, a local barbecue place, closed in 2014, after 48 years. You can talk to five different people and get eleven different opinions: it was either absolutely amazing, the best ribs ever, or pretty horrible. I remember making a trip to it years ago, when I lived on the north side, with friends who spoke highly of it. I recall it being too sweet, like so much else here.

It’s impossible to discuss the pathetic state of Hyde Park restaurants without considering the shadowy giant that controls everything here: the University of Chicago. There are entire books devoted to the racial history of Hyde Park and its peculiar class politics, which have resulted in the collusion of a black upper class and a black middle class with a wealthy university, home to one of the best medical schools and research institutions in the world, that refused to open a trauma centre until pressure from activists forced it to do so. As I’ve written before here, Hyde Park is a cross between a military installation and a company town. There are guards with guns everywhere you go, sometimes stationed even outside the Starbucks on 55th. Apparently, marauding gangs are snatching giant Frappuccinos from the hands of hapless students and disappearing into the depths of the south side to indulge in midnight caffein-riddled orgies before emerging again to engage in jitter-induced shootings, or something. Yes, Hyde Park is deeply racist (as is Chicago, a point brilliantly made in this Gawker piece) but its racism is shot through with a class collusion between its various elites that include white people and several communities of colour and a rapacious university that functions like a developer.

As far as anyone can tell, a business can’t open here without the explicit or implicit permission of the university, which is engaged in a multi-year push towards hyper-gentrification, the cornerstone of which will be the Obama library. Possessed of considerable wealth in an area that has historically been underserved and therefore yields lots of cheap land for development, the U of C has steadily gone about recreating Hyde Park in the image of what it imagines an urbane and urbane area looks like. The redevelopment has led to some strange kinds of rebranding, such as naming 53rd street, the main artery, “downtown Hyde Park.” People seem unconcerned about the fact that the “town” is only a few blocks wide every way and is actually a neighbourhood. In its attempts to make Hyde Park a destination spot, to limited audiences (cops are constantly monitoring, arresting, and even shooting anyone they see as not belonging), the university has allowed for the introduction of upscale restaurants like the Promontory and A10, both of which are very good (as is the more established Piccolo Mondo) and in line with Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s ambitions to increase Chicago’s reputation as a city famed for its restaurants.

There is an excellent restaurant scene in Chicago, on the higher end. I’ve nibbled at the edges of it, and am always left in orgasmic bliss at the depth of taste and artistry displayed there. But Chicago, unlike, say, New York, is not a foodie town because that depth does not extend to its general culinary scene, to places where one might go, say, after work to pick up a takeout meal or to gather with friends. There are such restaurants in neighbourhoods like Uptown and Edgewater with a range of great food and cuisines, but for the most part, Chicago neighbourhoods remain wastelands. When I did more beat reporting, I grew accustomed to stuffing a can of salmon and pasta into my bag because I knew I’d inevitably be somewhere around mealtime, without a restaurant in sight that wasn’t either a greasy dive or an extremely expensive gourmet restaurant.

Chicago is an aspirational city — how can you not be when saddled with the moniker “second city?” Its promotional materials often repeat the phrase “world-class city,” which, it fails to realise, is a clear sign that it is not. There are several elements of the city that prevent it from being a “world-class” city — its racist transit system is one — but it has succeeded in gaining a reputation for fine dining, encouraged by both the last mayor, Richard M. Daley and its current one, Rahm Emanuel. As a result, Chicago is home to destination spots with international reputations. It is typical of Chicago, with its immense inequalities, that it is simultaneously known for its many food deserts and for being Bon Appetit’s 2017 “restaurant city of the year.”

Until fairly recently, the university’s class aspirations meant taking pride in its carefully nurtured antique patina (although founded in 1890, it is designed to look like a Medieval institution). Today, the University of Chicago of the twenty-first century is determined to be as modern as possible and its various culinary experiments (recall: nothing opens or stays open here without its approval) can only be described as weird. One of its newest dorms, Campus North Residential Commons, is also the location of an Italian restaurant, Nella Pizza e Pasta. The ABC food critic Steve Dolinksy (“Hungry Hound”) declared, in a favourable review,”You’ve got to be pretty excited if you’re a college student.” But the restaurant seems beyond the reach or the lifestyles of average U of C students, who function in an intense academic environment. It’s likely that their preferred diet is Red Bull and pizza — cheap pizza, about $3 a slice — so one can only ask: Who puts a fine Italian restaurant in a dorm? Who is going to go to a fine Italian restaurant in Hyde Park in a dorm?

Well, lots of people, it turns out, and Nella Pizza e Pasta may be everything food critics say it is, but it’s more the kind of place students’ parents take them to, rather than the sort of they can or want to frequent; it’s designed to be a destination spot for everyone else. Building a designer residential dorm in an area near the famed Court Theatre and the Smart Museum (both owned by the university) signifies that the area is to be a destination spot for people outside and inside the neighbourhood looking for a night out, part of the U of C’s drive towards creating an economic ecosystem for itself which, you could argue, it has a right to do. Except that such efforts at gentrification inevitably come at the expense of the surrounding community. The university, with its ample millions could, of course have made a simpler commitment. A worthwhile culinary experiment, even with the relatively wealthy student population at the U of C, might be … free food? Or cheap food that is excellently prepared, nutritious, and utterly delicious? As is the fashion among elite universities these days, the U of C announces changes in admission policies to increase the chances of low-income students. But it’s not enough to simply admit poorer students, you have to make it possible for them to survive in your institution and its neighbourhood (I’m happy to be corrected on any of this, but my understanding is that the university’s meal plans are not entirely popular).

Unlike Nella, which offers full meals, the restaurant Packed, with the tagline “Dumplings Reimagined” and which was recruited by the university, never even bothered to pretend to actually serve such. Eagerly anticipated, it took over nine months to open, and four to close. For ten dollars plus tax, I had four tiny dumplings (the cheapest deal I could find), none of which tasted anything like their names, such as Mac and Cheese, Tamale, Pozole, and Duck. The idea, poorly executed inside flavourless wrappers, was to create “deconstructed” versions of entire meals inside dumplings. But, really, how much can you really, ah, pack into a dumpling that fits in the centre of your palm with ease, even aided by an esoteric (and often misapplied) theoretical term? To the very great credit of U of C students, they laughed it out of existence.

Like Whole Foods, even the chains here can’t be bothered. Harold’s, a local franchise and elsewhere justly famous for its fried chicken is here dismal, in a location that feels claustrophobic and whose offerings are indifferently made; the chicken lacks any flavour and the skin slides off, defeating the point of fried chicken (for those seeking better: the best fried chicken in the neighbourhood is at Rajun Cajun). At Roti, there is at least a range of fillings and many are not bad but the fact that they all get mushed in together makes it all pointless (to be fair, this is probably the case with Roti everywhere). At Chipotle, most of the food is dry, and Native Foods, otherwise a decent option elsewhere, as in the south loop is, again, tasteless and dispiriting.

To be fair: Restaurants are not always about the food. Consider Valois, which shall forever remain untouchable, beloved of even the most demanding food writer. It is one of the last Greek diners, a long-standing neighbourhood fixture where people make regular plans to meet with old friends, and is cheap and delicious, fulfilling every requirement of its type. Bridgeport Coffee, to which I am deeply attached as a regular (as I am to Valois, full disclosure), serves the best coffee and is haunted by many other regulars hunched over their laptops. Medici is legend among generations of Hyde Parkers, and their fondness for it has as much to do with their memories associated with it as the quality of the food (I have never been too impressed but many love it).

And then there is Plein Air, the Studio 54 of Hyde Park, where you’re not present for the food but to see and be seen. Instead of Bianca Jagger on a horse or Cher and Liza and Andy and Elton, there is the Famous Gender Theorist or the Famous History Professor and is he with X, who’s headed to Germany on that postdoc? The chatter in the always-crowded place buzzes and ebbs and flows on high tides of academic anxiety; on a visit, I was glad to have brought along my New Yorker and not my Vanity Fair and even then felt inadequate. Two graduate students spoke rapidly not about papers and books but about people. One asked the other, “Did you see that Y received that grant?” “Yes,” was the reply. For a few seconds that news hung in the air between them, heavy with their own ambitions temporarily thwarted, of hopes and possibilities momentarily quashed; the envy rustled in the air. But then they continued in their rapid fire way, quickly batting gossip back and forth with the ease of tennis players at Wimbledon.

Food is complicated and it can be hard to maintain culinary standards in a place like Hyde Park which is, first of all, in the Midwest where everything is rendered as flat as the landscape, and where sugar is a food group (the opposite of bland is not fiery-spicy, a common Midwestern misunderstanding, but flavour). A friend points out that while the neighbourhood might have many immigrants, they don’t actually live here in immigrant communities as is the case in neighbourhoods like Uptown and Edgewater (Hyde Park’s subtle and not-so-subtle forms of xenophobia are … complicated, and to be considered in a separate piece).

The university dominates the neighbourhood and only sees it as a cash cow, periodically selling off parcels to raise money, and it is creating a fake downtown bristling with chains and boutique establishments: prime conditions for the homogenisation of taste and sensibility that dooms culinary experiments and bravery or simple boldness, except in the more expensive restaurants that are designed to impress visiting scholars taken out on departmental expense accounts, and well-off outsiders.

Things are unlikely to change. Not bad is the best we can hope for.

Still: Restaurants and cafes aren’t just places where you go to eat food: they inevitably form ecosystems where groups of people converge, gather, mill, eat, and leave, making space sometimes for entirely different crowds at different times. Up north, the deeply missed Punkin’ Donuts in Boystown has disappeared, taking with it a sense of place and stability for people who felt like misfits everywhere else. It’s unlikely that they were there just for the donuts. Here, Snail Cafe is beloved among several queers going back generations, as the one place where they felt comfortable being out in public. The Dunkin’ Donuts on 53rd is a regular hangout for elderly residents.

Which is to say: not every eatery has to be a brilliant culinary experience. You go somewhere because it’s where you have breakfast with your pal every month before work, or to another place every morning because there’s wifi and coffee. You remember a place not for that soggy pizza but because it was the site of that date with that guy in the middle of your senior year, whose name you can’t remember. You slept with him because, you thought, why let an evening go completely to waste? He was fine, not bad, like the food you ate.

**********

Yasmin Nair lives in Hyde Park, and would like to never again hear about Ribs and Bibs.

*Added December 9, 2018

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

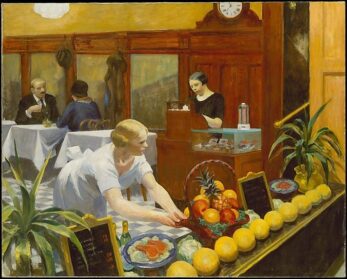

Image:

Tables for Ladies, Edward Hopper, 1930