“This is an attempt to trace the conditions that reproduce the logic of the suffering/savage slot, even as I position my own work within those conditions.”

One evening, over a decade ago, I sat next to Joseph Hankins at a Chinese restaurant in Uptown, where a large group of us had decamped after a meeting of radical queers. Joe was still a doctoral candidate at the time; I knew his project had something to do with Japan, but not much else beyond that.

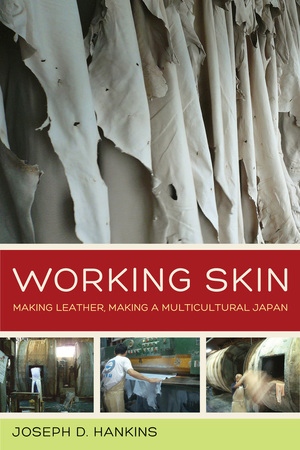

Over the course of a delicious meal, as I speared and devoured shitake mushrooms and seafood, he described his then still incipient research to me. I sat, riveted, falling in love with a project that I knew, in my gut, would prove to be as fascinating as it has turned out to be. Joe and I lost touch for a while, reconnecting on Facebook only a couple of years ago, but it’s no exaggeration to say that I’ve often thought about his work and been following it to its current state. Working Skin: Making Leather, Making a Multicultural Japan was published by the University of California Press in 2014, and in what follows, I provide a very preliminary and inevitably incomplete sense of what the book is about. This is not a straightforward review of the book. Instead, I rely on extensive quotes to illustrate the points made in it and I only mean for this piece to announce a forthcoming interview with the author.

Joe is from Lubbock, Texas, and when he first joined the PhD program in anthropology at the University of Chicago in 2001, he did so with the intention of of researching “language use, gender, and sexuality in Japan” (Working Skin, xi). And then one day he found himself at a leather tannery in Togichi Prefecture, north of Tokyo, and approaching a very different project. The trip to the tannery was to be a “brief study tour of Buraku-related issues.” The Buraku have historically been leather tanners and one of the most stigmatised groups in Japan. While Joe knew something of all that, he was not there to study them directly but had come along at the invitation of his sociology professor.

He introduced himself – a white, six foot two tall American man with red hair who stood out noticeably in the crowd – as both a graduate student at his university and a native of Lubbock, andwas surprised at the response of the tannery manager: “Lubbock? It’s flat and dry and ugly there.” Joe had no argument with the description of the place, but wondered about such intimate knowledge of a relatively unknown Texas town, not a tourist destination, on the part of the manager.

As it turned out,

…the majority of the rawhide used at this tannery came, in salted crates, from my hometown, shipped through Los Angeles to Tokyo and then up by train to Toguchi, to be tanned into leather there, 7000 miles away from where it had started. A small group of the tannery management had traveled to Lubbock several years prior to tour ranches, feedlots, and slaughterhouses in the Texas Panhandle; they knew Lubbock was flat, dry, and ugly because they had been there. I was stunned by this information. Growing up in Lubbock, I had always been aware that the ranching and meat processing industry was large – anyone with a working nose is aware of the cattle…but I had not anticipated that parts of the cattle in the feedlots outside my hometown, feedlots where high school friends of mine worked, might end up on the other side of the planet where I too then lived.

Joe continues,

I typically narrate this moment as one of epiphany, a paradigm shift for my project: I decided to take contingency as a sign of providence, discard an examination of language use and gender, and instead take up a study of Buraku issues as they connected to global commodity circuits reaching as far back as Lubbock, Texas. “Providence,” however, is a gloss that deserves some unpacking; the ethical and political impulses it encompasses are deeply entangled with the ethical impulses that are part of the subject matter of this book. (xiii)

It should be made clear that Working Skin is not an account of some personal journey of self-discovery and affirmation, or some convoluted tale of a white man finding his soul in the mysteries of Japan. Rather, it’s a dense, complex unpacking of “global commodity circuits,” as well as a dissection of the very impulses that constitute such work in the first place. Or, as Joe puts it,

…I do not dwell on this reflexive question from a vantage point of personal experience. I instead offer it as a way of thinking through the conditions that enable and shape my own disciplinary practices. In many ways, this consideration, along with the conclusion that considers at greater length the role a book like this has in Buraku politics, is meant as an explicit response to a challenge that, though decades old, has shaped my work as an anthropologist. (xvi)

The Buraku constitute one of Japan’s dirty secrets, a scab over the smooth skin of ethnic harmony in which the country takes pride. Working Skin considers not only the history of stigma that the Buraku have endured for centuries, but the processes by which the community worked to rid itself of it. As Joe’s research indicates, these entailed conventional methods of social transformation within Japan as well as plugging into a global transactional framework of “human rights” discourse, located particularly in the United Nations and its systems of classifying cultural groups as deserving (or undeserving) of protection and legal recourse in matters of discrimination. These processes inevitably meant developing a language of woundedness, of oppression, and of evoking transnational solidarity with the Dalits of India. And they meant the eventual creation of “Buraku” as not only a loosely identifiable group of people who shared the stigma of an occupation but as a fully defined and modern identity formation.

As he describes it,

The work of the political organizations, then, in contrast to that of the factory workers, became that of producing an identity, clad in the essentialized authority of an ontological state. If factory laborers, working through the demands of skins of animals, created leather, stigma, and pollution, the political workers, working through the demands of skins of representation, endeavored to produce a pure core identity that could be abstracted from the polluting realm of action. It was a constant source of struggle, however, to locate that core authentic identity and, more importantly for the political movement, to have people cast as Buraku claim that identity within themselves. (107)

Working Skin is an ethnography of the contemporary situation of the Buraku people. However, the project proceeds by pulling apart the practices, …This book is an examination of the labor involved in identifying, dismantling, and reproducing the contemporary Buraku situation; it is also an examination of the labor involved in overcoming this repeated refrain. Ethical orientations and economic relations are being formed and reformed in the tanneries of Tokyo, the offices of human rights workers, and the practices of Western ethnographers, all in ways that are linked together across geographical distances…This is not a book that simply demonstrates that Japan is multicultural. Instead, I analyse how the incitement to multiculturalism disciplines both those who produce representations of social difference in Japan and those who are summoned as evidence in such a project. I show how the demands of liberal modernity arise in the work of Buraku laborers and the govdernmental and nongovernmental organizations that represent them. This is an attempt to trace the conditions that reproduce the logic of the suffering/savage slot, even as I position my own work within those conditions.

More broadly, then, Working Skin is an examination ofongoing changes in global capitalism and styles of political representations, that is, in the geographies of management and imagination that, among other things, have enabled practices of anthropology such as my own. (xvii)

I have the very great pleasure of announcing that I will soon be publishing an interview with Joseph (along with writers like Liza Featherstone, Roger Lancaster, Chase Madar and others). My very patient subscribers have been waiting for the series, and I wanted to use Joe’s book as a springboard for demonstrating what the format will be like. For each author and interview, I’ll provide a rough synopsis like the above, as a teaser, but the interviews themselves will be behind the paywall.

I’m also developing a yet-unnamed series, on the intellectual histories of research projects. I define “research projects” quite broadly: they might be graduate research papers, undertaken only over the course of an academic semester or quarter, long-form investigative or analytic work undertaken by a journalist or cultural critic, dissertations, or monographs. Whatever form they take, I want to devote time and energy to discussing what goes into the making of intellectual work, beyond the usual, “So what inspired you to do this?” questions.

Over the last decade or so, the United States in particular has increased in its historical tendency towards anti-intellectualism, and what is so startling although not entirely unsurprising is to see some of this manifest itself even within the publishing world and academia. A lot of the current state of affairs, with writers and academics bitterly ruminating that writing, analysis, and research are useless endeavours and that no one should really get anything beyond a college degree, if that, has to do with the bitterness of groups like underpaid adjuncts angry that their class aspirations might go nowhere, as I’ve written here and here.

But intellectual work, broadly defined, matters, and rather than angrily dismiss its value, we might consider instead thinking and rethinking its place in the world, and working to make a case that the essential values we claim to hold dear, including those that what we term “democracy” and “freedom,” owe everything to including a spirt of intellectual inquiry that embraces instead of rejecting abstractions, thoughts, and lines of query that might, eventually go nowhere in terms of published work but whose formation in themselves are the driving engine of what we might term public life itself. Or, simply, that the life of the mind, a phrase we are now accustomed to use with high irony, [insert linke to coen brothers] really does matter, that it’s okay to pursue objects of inquiry with no end in mind other than simply seeing where a train of thought might lead.

We might also stop and think of the many racial, gendered, and classed connotations of the more recent turn towards anti-intellectualism. Who gets to choose to bypass the admittedly too-often expensive years of higher education? Who gets to take degrees and then tell their students that such are useless?

I’ll be indirectly and directly engaging these questions in future months, and, again, thank everyone for their support. Some, all, or many of you know of the Dire Situation in which I find myself these days, which has made consistent output difficult at times, but you’ve continued to support me via subscriptions and donations, and that support has kept me afloat in more ways than one.

I’ll leave you with some last bits from Joseph’s book. Here, he describes the skins arriving at the tannery and the material and immaterial consequences on the bodies and collective identity of the Buraku.

Across the steps of tanning – hair removal, scudding, deliming, tanning, and stacking – the skins move in and out of the drums, in batches of seven hundred, one at a time, and undergo fixation: they slowly change consistency, elasticity, and durability as their molecular structure becomes fixed and made less susceptible to rot. At the same time, the movement demanded for their fixation slings burning liquids and stinging fumes across workers’ arms, faces, noses, and eyes, bringing a sharp focus to these parts of their bodies. Eight men work this initial part of the leather. Day after day, year after year, and occasionally after generation, they respond to the call of the skins and surrender hands, arms, legs, backs, eyes, and ears to the obligations of the skin-to-leather transition. They move the skins from cage to leather, all the while dripping and splattering chemicals across their own bodies and the bodies of the men working next to them. Vitriolic acid, chromium, lime, neutralizing enzymes, sodium – all of these are slung across the men’s bodies as skins are slapped down one by one on pallets; they splash back onto the bodies as the skins are thrown into the wooden drums, and they creep into the workers’ eyes, noses, and mouths as the chemicals are freshly mixed. (54)

The skins, arriving in bulk, summon to this task anywhere from one to five sets of hands, arms, legs, backs, and eyes. These bodies work together in coordinated rhythmic ease, stepping back, grabbing, straightening, twisting and unfurling in a punctuated effectiveness of skin movement. The process uses these men simply for their bodies; who they are matters less than their ability to get the job done. At the same time, however, this reduction of self only summons certain kinds of people. The job is dirty, dangerous, and difficult (kitanai, kiken, kitsui). Economic necessity and lack of other options motivate most of the workers to come to this job each day. At the same time, this dehumanizing labor draws from the chronically underemployed, it also potentially marks those people – their bodies, their employment records – as a certain kind of people, as Buraku. (52)

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.