Medium has become the hotspot for talking about poverty and related social justice issues. Talia Jane recently wrote a long “open letter” to the CEO of Yelp, where she worked in the “consumer support department.” She detailed her poverty and inability to even buy groceries for herself on her salary. Soon after, she was fired; the company has so far claimed this had nothing to do with the letter.

Jane’s letter went viral, becoming the top-ranked piece on Medium. It has earned both admiration and ire. On Medium itself, Stefanie Williams shot back at Jane: “This is about this girl’s personal responsibility to be an adult and find a job, or two…an affordable living situation and an affordable city in which to work.”

I’ll have more to say in a separate post about this current and disquieting trend towards poverty porn and the backlash in the form of poverty shaming — in my view, neither takes account of the systemic conditions that create poverty in the first place.

But for now, I’d like to focus on the irony of writing about poverty on a platform like Medium. Both Jane and Williams write at length about the topic, but if neither of them was paid for their work, they’re both being exploited by a site whose payment practices are dubious and which in turn create greater poverty for writers and others.

It has become popular to criticise Huffington Post for not paying most of its writers. A recent interview with Huffington Post UK editor in chief Stephen Hull, where he said that paid writing could not be “authentic,” has led to widespread anger against him. I’ve been critical of HuffPo in the past (and have refused, twice, to even be interviewed by them because of their exploitative practices), but also of outlets like Guernica and Open Democracy for not paying their writers.

But at least HuffPo and the others are open about their practices. On its site, Medium reveals nothing at all about its payment practices. There are lots of words, like “community” and this priceless bit:

However, the real value of Medium isn’t our tools. It’s all about the network, the connections with other people, and the stories you create. Well-designed networks reduce friction and help good stuff be found. Connections allow the whole to become greater than the sum of the parts and new paths to discover and build meaning. After all, isn’t that what every writer wants?

Well, actually, writers like me want to get paid and to be regarded as working professionals. As it turns out, Medium pays a select few but as of today that information is only to be found in this Atlantic piece and a Wikipedia entry.

There are small, lefty journals like Dissent that pay writers different amounts, and which ask tenured professors, for instance, to donate their labour so that beginning or struggling writers might be paid for their work. So, this practice of paying some but not all is not a shocking new one. In the underfunded world of left publishing, it’s considered one of the more equitable ways to distribute scant resources (I actually think it’s time to change the practice and come up with ways to pay everyone, but that’s a tale for another day).

The big difference between, say, a small lefty journal and Medium is that the latter is owned by one of the richest people on the planet. Its founder is Evan Williams, the co-founder of Twitter, whose net worth is $1.71 billion. In contrast, Arianna Huffington, founder of Huffington Post, is worth a piffling $50 million. With that kind of money, Evans could easily have opted to build a site that paid for writers and a full-fledged editorial and publishing team. Instead, he now runs the Zen version of HuffPo, a HuffPo Lite which successfully erases the fact that much of the labour that makes it a commercial success is unpaid.

It’s ironic to see pieces like those by Jane and Williams on poverty on a site that is part of the neoliberal structure that helps create the dire economic conditions they write about. Medium is part of a system that squarely puts the responsibility of economic and physical health on the shoulders of individuals. And the hallmark of that severely individualised response is to demand that people take on the responsibility of making money by “monetising” and branding themselves, by producing massive outputs of work for free on such sites.

Reading Jane and Williams — and circulating their pieces — gives us the illusion that we get it, that we are that much closer to understanding how badly off we are, how broken the system is because we can empathise with their conditions.

In fact, neither piece offers any systemic analysis. They tell good stories, one about the direness of poverty and the other about how to escape it, but that’s it. When relayed through their duelling accounts (they have inevitably taken matters to Twitter, making Evan Williams even wealthier), our understanding about poverty remains on the level of personal drama.

They’re posting these stories on a site owned by a billionaire who is profiting off their labour or, if they got paid, the labour of many others who contribute their work for free and who don’t know that some among them get paid. It’s easy — and, yes, necessary — to criticise CEOs like Yelp’s Jeremy Stoppelman. It’s easy to rant and rave in populist terms about the need to pay everyone a living wage.

But we might ask: What is it about writing that we don’t see it as something that deserves compensation as labour? And why do we think that it’s okay to pay millionaires and billionaires with our labor instead of demanding that they pay us?

I have an update on this piece, “How to Be Poor,” which you can read here.

For more on Writing for free, see also:

Killing You Softly With Her Dreams: Arianna Huffington’s War on Sleep.

Scabs: Academics and Others Who Write for Free.

I’m a Freelance Writer: I Refuse to Work for Free.

Is Your Reading Material Ethically Sourced?

“Scabs and the Seductions of Neoliberalism.”

“On Writers as Scabs, Whores, and Interns, And the Jacobin Problem.”

“Make Art! Change the World! Starve!: The Fallacy of Art as Social Justice, Part I.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

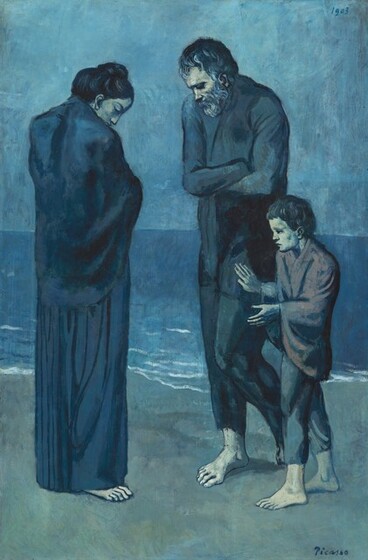

Image: Pablo Picasso, The Tragedy.