Excerpt: All around us, animals penetrate capital.

I. From Russia, with Cute and Fuzzy Dog-Love

A striking bronze statue of a dog sits in the Mendeleyevs-kaya subway station of Moscow. The city has been home to roving packs of semi-feral canines since the Soviet era, and many of them have made their homes in the warmer spots of the stations. In the old days, the dogs lived in the industrial zones of the city and often found their food while sifting through garbage. With neoliberalism came drastic changes in the city’s landscape. The old factories became shopping malls and apartment buildings, and the dogs were now compelled to learn a few new tricks. These included learning to travel back and forth between the city and the suburbs on the subway and riding escalators.

A 2009 article and video from The Sun shows the animals dog-napping on subway seats. One of they may have been Malchik, the dog now immortalised in bronze, who is described as “gentle” in a Wall Street Journal article which reported that she was repeatedly stabbed to death by a crazed fashion model: “[H]orrified celebrities and ordinary city residents raised money” for the memorial.

video here (also from the WSJ):

There is so much to ponder in this story of the mad model and the unsuspecting dog. The description of her death evokes sadness and the sounds of a crazy woman stabbing a helpless dog. It is unusual to hear of a dog being stabbed; we are more likely to hear of them being clubbed or beaten or kicked to death. This story of stabbing brings with it a history of deliberate intent and passion gone awry.

The affective register continues with an accompanying photograph of the dog’s statue being caressed by a woman while flowers lie at its base. It’s unclear whether the dog got her name before or after her death. What is clear is that Malchik’s bronze memorial, shrouded in affect, effectively recuperates a narrative of dog-ness into a story about a city’s beloved pet.

As it turns out, the Moscow dogs are not at all pet-like, even as they have finely attuned their behaviour to maximum effect. In a WSJ video, we see one of them stand in front of a couple for a couple of minutes, and then turn away, having quickly discerned that these humans will not be sharing their food. A zoologist who has studied them asserts that they have learnt to not nuzzle or touch humans, knowing that their physical proximity is not always welcome. While they are not exactly wild, they are also not the kind of cute and cuddly dogs you would want to take home to your child.

The statue of Milchak, endearingly posed sitting down and looking upwards at an invisible human master, mitigates that loss of doggy-affect – even though she was never a pet. Rather than standing and staring at us, as the dog in the WSJ video does, she sits as if at someone’s feet and looks up. In death, the stray dog is domesticated.

All traces of ferality are made to vanish, replaced by the bronze warmth of a pet for the whole city. But such a vanishing of animality into the affective register of universal petness comes with a cost to us. Our affective relationship to animals helps structure neoliberalism.

II. From Animals to Pets: A History of Love, Fidelity, and Suffering

The Moscow dogs are not a unique phenomenon. Such roving packs are common sights in cities like Calcutta and Delhi which, despite their recent ascendancy into neoliberalism, are still burdened with the kind of economic inequality that makes the lives of wild and stray dogs metaphors for the kinds of lives endured by many of their human residents. Indeed, some of the fascination with the Moscow dogs (the news story made its way around the internet) may have to do with the uneasy sense that the city is not supposed to function like one in the “third world.” Such dogs would likely have been common in England or the United States until well into the 19th century, but “animal control” organisations now ensure that all strays are quickly and effecticely corraled and either domesticated or euthanised.

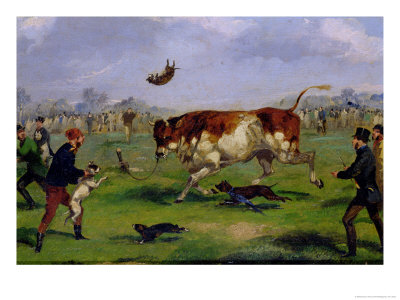

In the U.S, suburbia has brought with it a perceive need to possess animal companions and a sharp increase in the breeding – and miniaturising – of dogs and cats has resulted in forms and shapes that would be unrecognisable to an average 19th century urban or rural citizen. In Charles Dickens’ novel Oliver Twist, the villain Bill Sykes is accompanied by an equally villainous bulldog named Bulleye whose loyalty to his master remains unchanged even after many beatings. Bulldogs were so named because bull baiting was a popular sport in Medieval England, and the dogs used in these events were gradually bred to best enable them to tackle their helpless prey (positioned as combatants). As is evident from the images of the period, the bulldog of an earlier time had longer and sturdier legs. Today’s bulldog, with its lower jaw far outreaching the upper, the multiple extraneous folds covering much of its face and the short stubby legs that go nowhere fast is a cartoon of a dog. But the bulldog of Dickens, with longer legs and a rather different face, bears no resemblance to the squat and low-hanging dog with which we are now familiar.

The history of animals turning into pets designed to do no more than look cute while being (often, but not always) lavished with attention is inextricably linked to the history of the animal rights movement. That latter history forms the riveting tale of Kathryn Shevelow’s For the Love of Animals: The History of the Animal Protection Movement.

The history of animals turning into pets designed to do no more than look cute while being (often, but not always) lavished with attention is inextricably linked to the history of the animal rights movement. That latter history forms the riveting tale of Kathryn Shevelow’s For the Love of Animals: The History of the Animal Protection Movement.

The focus of Shevelow’s book is the Ill-Treatment of Cattle Act of 1822, described as “the first national law anywhere in the world, passed by a democratically elected legislature which dealt specifically and entirely with cruelty to animals.” But the Act took decades to come to pass, and Shevelow gives us histories of the various public and philosophical discourses that made it possible, along with biographies of the men and women who kept up the pressure to ensure that animals were actually seen as deserving of rights and freedom from harm. These include the famed beauty and early animal rights philosopher Margaret Cavendish, and Richard Martin, who helped pass the Act and was among the founders of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Shevelow is careful to give us the histories of lesser-known but equally diligent activists like Arthur Broome, who called the first meeting that led to the SPCA, and spent much of his life toiling in poverty while devoted for his cause.

It may seem shockingly obvious to us today that animals should be treated without cruelty, given how much of the Western world focuses on animals as a natural part of rights discourse (whether or not that template of rights can or even should be part of a “natural” discourse of rights is a topic that cannot be explored at length here). But England was for a long time home to the most horrifying forms of cruelty to animals, and bull-baiting was only one manifestation of that. Until the passage of the Act, animals were considered mere property and incapable of feeling pain.

By the eighteenth century, England had earned a reputation as the cruellest nation, based on what foreigners saw of its treatment of animals (my friend J., a historian of the period, is quick to remind me that it was also notoriously cruel towards humans). Carts and coaches were routinely overloaded, and the horses or donkeys dragging them were badly beaten and crippled. Shevelow gives a telling example of “[o]ne man who had torn a horse’s tongue from its mouth – it is striking how often this particular cruelty was reported in the newspapers during the century – was arrested but, since there was no evidence he had done it to injure the horse’s owner, he was set free.”

torn a horse’s tongue from its mouth – it is striking how often this particular cruelty was reported in the newspapers during the century – was arrested but, since there was no evidence he had done it to injure the horse’s owner, he was set free.”

The work of prominent writers and reformers like Alexander Pope and Jeremy Bentham was creating more sympathy for the idea that animals had the right not to suffer, and that, in turn, necessitated an acceptance of the idea that they could suffer in the first place. At the same time, people were acquiring animals as pets and keeping them in their homes. Popular empathy towards animals was also greatly enabled by numerous stories about the devotion of beasts to their human companions. In July 1805, a shepherd leading his flock to pasture in the Lake District heard the howling of a dog. Searching for the source of the sound, he eventually came upon a small terrier apparently guarding the decayed and headless body of her master, Charles Gough.

The terrier, named Foxey, became a national heroine and both William Wordsworth and Sir Walter Scott penned poems to her. Scott’s words in particular are indicative of the strength of the affect engendered by the public’s growing sense that animals could suffer, and the increasing tendency to anthropomorphise them:

How long didst thou think that his silence was slumber?

When the wind waved his garment, how oft didst thou start?

How many long days and long nights didst thou number

Ere he faded before thee, the friend of thy heart?

The tale of Foxey began what has now become a genre of stories about dog fidelity. For a while, however, the story of her incredible devotion was almost marred by a suggestion that floated about for a while: that she may have actually stayed near Gough’s body in order to sustain herself by eating off his carcass. But this other and darker (and perhaps more realistic) story was quickly squelched as a vicious rumour and Foxey regained her status as the Dog Who Stayed By Her Master Even After Death.

The idea that animals could feel such fidelity and love certainly helped make the case for them as sentient beings worthy of our regard, and this marked a change from a period when animals were tried for crimes against humanity. In 1386, according to Shevelow, “a sow convicted of murdering a child in Normandy was forced into men’s clothes before being hanged in the public square.” But crimes by animals were not just those that came about by accident or in defense; bestiality was punishable by death (and was a crime in Britain till 1861). In 1677, one Mary Hicks was found guilty of having sex with her dog; the case was based on charges by her neighbours. In court at the Old Bailey, the dog sealed his fate and hers when he greeted her by wagging his tail and “making motions as it were to kiss her.” Hicks was forced to watch him hang before she herself was executed. As we shall see in later sections, such notions of animal criminality are not entirely absent from today’s public discourse.

With the passage of Martin’s Act and subsequent ones that also ensured the rights of domestic animals, the animal protection movement soon began to gather momentum and legitimacy. In 1835, Princess Victoria, a lover of animals, became a member of the SPCA. She became Queen in 1837 and, in 1840, the SPCA became the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, ending its long and beleaguered history as an organisation struggling to survive.

III. Be My Beast Forever: Dracula as the Un-Affective Vampire

As animal rights began to expand, so did the vast reaches of the British Empire. Victorians had a sometimes literal feast of animals to pick from, and they included creatures that stood out for their difference from the natural fauna of Britain: gorgeously hued peacocks, enormous elephants, and strange creatures like the platypus which looked like it had been stitched together from parts of other beasts. Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859; that and other works in the growing field of evolutionary science fuelled a restless curiosity about the origins of humans – and an anxious desire to know and understand the dividing lines between man and beast (and man, indeed, was the sole concern here).

The fiction of the period following Darwin’s work would reflect the anxiety about origins and the tenuousness of the idea that man was the centre of the universe. It would also reflect an anxiety about what the expanding Empire could bring into the nation. In 1886, Robert Louis Stevenson published The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a novel about a scientist who discovers a way to unleash another and more vicious man within. In 1896, H.G. Wells wrote The Island of Dr. Moreau, about a mad scientist’s attempts to turn animals into men. Both these novels were about botched scientific experiments and embedded in a combination of suspicion and hope about what science could bring to the world.

While both works explored the concept of a beast or beast-like creature within (or, in Well’s book, the man within the beast), it was Bram Stoker who took the fear of the animal within into the supernatural realm, in Dracula. Borrowing from established European folklore, Stoker created a narrative about a man who could turn into a beast while sucking the blood of humans to stay alive. As Count Dracula, we first encounter him as an extraordinarily gracious human host greeting Jonathan Harker, the first of the narrators of the story, as he enters Dracula’s castle in the Carpathians. As the nights go by, Harker discovers that he is a prisoner of the Count and slowly begins to suspect his true identity. His fears come true one night when he looks out of his window one night and sees Dracula leaving by a window, but not in the way any human might:

I was at first interested and somewhat amused, for it is wonderful how small a matter will

interest and amuse a man when he is a prisoner. But my very feelings changed to repulsion and terror when I saw the whole man slowly emerge from the window and begin to crawl down the castle wall over that dreadful abys, face down, with his cloak spreaking out around him like great wings….I saw the fingers and toes grasp the corners of the stones…and by thus using every projection and inequality move downwards with considerable speed, just as a lizard moves along a wall.

Much of the fear of Dracula comes from the understanding of his ability to metamorphosise into other animals. He can change from man to wolf, or from man to bat and back again. In other words, Dracula is not a man with a beast within – he is something else altogether, someone who looks like a man but can change solidly into an actual animal. That makes his human prey much more vulnerable, and it literalises a discourse of anxiety about the beast within.

But what makes Dracula most alarming to his opponents is his lack of affect. Nowhere in Stoker’s text is there a hint that he particularly cares for anyone or anything; all are merely future corpses to aid his way to relative freedom in London.

In today’s renditions of Dracula or the imitations thereof, we are given hints – and more – of longing and even pain raging within the vampiric breast. Angel, of Buffy the Vampire Slayer fame and the ubervampire of the millennium, is a tortured soul. He is also a thoroughly modern vampire, given to modernist restraint in his art collection and furnishings and, as Xander, a friend of Buffy, once put it, “that whole tall, dark, swishy-coat thing.”

Today’s vampire no longer speaks to our anxieties about the beast within. Our representations of them evoke little more than humans gone slightly awry, essentially people who can change from ordinary humans to humans with fangs and bumpy foreheads, but who stay essentially human nonetheless. Even Dracula, on an episode of Buffy, is now merely a slightly morbid, slightly foolish vampire. Today’s vampire is no beast. He has great cheekbones and is a really cool dude who looks good in a wet shirt. In his stead, animals have been returned to their rightful place.

IV. Translating Temple Grandin: Autism, Animals, and a Bridge to Affect

What or where, exactly, is the rightful place of animals in a neoliberal world where we can no longer locate them within us or in the supernatural? The United States in particular stands at a nexus of extreme devotion to household pets and a sharp increase in farmed meat consumption. There are approximately 77.5 million owned dogs and 93.6 million owned cats in this country. In 2009, 22,281 cows were slaughtered, as were 5,800,295 chickens. There are approximately 304,000,000 people in this country.

I do not point out these figures to criticise the fact that we kill some animals for meat while we fetishise others as pets (and some, like rabbits, may function as both). Rather, I want to point to the discordant effects of affect in a country where pet ownership and kindness towards certain animals is valued even as we turn our eyes away from a massive meat industry whose immense growth and endless dissection of the product it churns out has enabled most of us to forget that there are actually animals involved in the process.

The last decade or so has seen the rise in a new kind of food literature. Where food writers of the past revelled in providing gateways to gastronomic travels cookbooks or treatises on the origins of cuisines, today’s food writers are assiduous about pointing to the failure of the farming and meat industry to provide sustainable and nutritious food and the cruel treatement of animals herded and slaughtered in conditions that are as dangerous to us as to them. The overproduction of meat has led to disastrous eruptions of food crises. As a result, organic and supposedly sustainable forms of farming have been gaining attention in the media. Along with this has come some amount of pressure on the commercial meat industry to reform its ways and ensure that its products are as humanely created as possible.

But does any of this really make sense? Is it really possible to create the conditions for “humane slaughter” without perpetuating the disastrous model of overproduction and overconsumption of meat that this country relies on? What does it mean to treat animals in a humane way when we are the humans who lead them to their slaughter? How do we begin to understand what “humane” means in this context?

The name of Temple Grandin, who has become something of a high priestess of the animal rights movement would most likely be invoked in conversations where such questions are asked. Grandin has earned some unique and contradictory distinctions. Besides her job as Associate Professor of Animal Science at Colorado State University, Grandin serves as a consultant to the livestock industry. In 2004, she receved the Proggy award from PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals). On its website citing Grandin’s work, PETA writes:

Renowned animal scientist Dr. Temple Grandin doesn’t seem like the sort of person who would receive PETA’s Proggy Award. An associate professor of animal science at Colorado State University, Dr. Grandin consults with the livestock industry and the American Meat Institute on the design of slaughterhouses! However, Dr. Grandin’s improvements to animal-handling systems found in slaughterhouses have decreased the amount of fear and pain that animals experience in their final hours, and she is widely considered the world’s leading expert on the welfare of cattle and pigs.

This is high praise indeed, coming from an organisation otherwise well known for guerrilla tactics like throwing paint at the fur coats of Anna Wintour, editor of Vogue. Grandin’s supposed success at making slaughterhouses more humane – and PETA’s bolstering of that supposition – comes in part because of a biographical detail that she has consistently claimed makes her more empathetic to animals: she is autistic.

Born in 1947 in Boston, Massachusetts, Grandin grew up with undiagnosed behavioural problems. In 1951, she was diagnosed with autism. Since she was one of the lucky ones of her generation to have a supportive family with access to resources, Grandin was able to continue and complete her education with a doctorate in Animal Science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Today, Grandin is well known as an inventor of various devices that are meant to provide more security and comfort to animals in their feed lots or on their way to inventions. As she often tells it in her many books (which tend to repeat the same anecdotes), her solutions can be modifications in the structures surrounding animals, like the sweeping curved corrals intended to reduce stress in animals being led to slaughter,  or as simple as installing lights at the end of tunnels so that pigs don’t balk at entering the darkness.

or as simple as installing lights at the end of tunnels so that pigs don’t balk at entering the darkness.

Grandin’s claim, explicitly laid out in her book Animals in Translation: Using the Mysteries of Autism to Decode Animal Behavior, is that she thinks much like animals do – on a visceral, sensory, and visual level – and that allows her the unique ability to grasp their needs. For her work and lectures on autism and animal science, Grandin has received numerous accolades and it is difficult to find any substantive critique of her, except on the occasional vegan blog where her assertions about “human slaughter” are roundly denounced (as is PETA’s award). Grandin’s theories about the link between autism and animal welfare dovetail our “love of animals” with our need to recognise and perhaps even overly fetishise people with recognised disabilities. Today, Grandin is enjoying unprecedented popularity in the wake of an HBO documentary on her life starring Clair Danes.

The problem with Grandin is that her proximity to animals along with her autism has become a way to construct a particular narrative about autism itself. Given her educational history, she clearly has a right to claim expertise in livestock environment design, but the fact of her autism does not necessarily make her an expert on the topic. In fact, Animals in Translation is filled with instances where she provides only the fuzziest evidence for her claims. In a section about frontal lobe functions, she writes: “A major autism researcher told a journalist friend of mine that if you compared the brain scan of an autistic child to the scan of a sixty-year-old CEO, the autistic child’s brain would look better.” She provides no details about this anecdotal evidence, not even the name of this “major autism researcher.”

It is in relation to animal experiences and lives that we find Grandin engaging a vastly affective discourse in which animals deploy human modes of interaction and values. In a section titled “Rapist Roosters,” she writes of finding a hen freshly killed by a rooster. Outraged at what she considers an overturning of natural law, she consults animal scientists and finds out that “the rooster courtship dance had gotten accidentally deleted in about half of the birds.” When a hen does not see the dance, she does not crouch down so that the rooster could mount her. Enraged, the rooster tries to force the hen to mate and, when she tries get away, slashes her to death. The result: corpses like the one found by Grandin.

It is in relation to animal experiences and lives that we find Grandin engaging a vastly affective discourse in which animals deploy human modes of interaction and values. In a section titled “Rapist Roosters,” she writes of finding a hen freshly killed by a rooster. Outraged at what she considers an overturning of natural law, she consults animal scientists and finds out that “the rooster courtship dance had gotten accidentally deleted in about half of the birds.” When a hen does not see the dance, she does not crouch down so that the rooster could mount her. Enraged, the rooster tries to force the hen to mate and, when she tries get away, slashes her to death. The result: corpses like the one found by Grandin.

On the face of it, Grandin’s explanation via her animal scientist colleagues makes sense, given our understanding of how overbreeding can have harmful effects on animals by making them lose some or all of their natural instincts. The problem is that Grandin makes no connection between this overbreeding and the sheer size of the livestock industry that she works with. Teasing out that connection would throw the whole enterprise into question – and presumably diminish her role as a consultant to the same industry. Instead, Grandin chooses to overlay the problem with affect by choosing a term as loaded as “rapist” to describe the roosters. This allows us to transpose and amplify an affective human trait onto an animal while ignoring the systemic reasons why such traits exist in the first place. In another instance, she writes about rats choosing “bad-tasting” painkillers over sugary solutions, and the notion that animals can discern good or bad taste based on human perceptions of the same is echoed in other parts of the book.

Yet, cats and dogs regularly and assiduously lick their own bums, will sometimes chew on their own vomit, and seem to consider toilet bowl water a particularly fine treat. Surely, the concept of “bad-tasting” food is not one that translates easily from the human to the animal world.

The level of affect in Grandin’s work is the result of living in a culture that only allows humans to interact with animals through a relentless anthropomorphising that requires us to transpose our emotions and likes onto them. It is also a necessity in a culture that needs to constantly locate farming in an idyllic imaginary of family-owned enterprises, rather than remember that it is a mega-industry that thrives on the use of hard labour, much of it undocumented.

On May 12, 2008, the U.S Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) division of the Department of Homeland Security carried out the single largest raid of a workplace in U.S history, arresting nearly 400 people working as undocumented workers. The raid happend on the premises of the Agriprocessors Inc. kosher slaughterhouse and meat packing plant in Postville, Iowa. The raid had cataclysmic effects on the town of 2, 273 and was marked by a particularly egregious and brutal set of procedures which involved treating undocumented workers as hardened criminals, even though many of them had done nothing more than work with false papers.

The Agriprocessors plant had been in trouble long before the raids. In September 2005, workers at the company’s distribution site in Brooklyn, New York, voted to join the United Food and Commercial Workers union and were challenged by the company, which falsely claimed that the workers’ votes were invalid because they were undocumented (the National Labour Relations Act places no requirement of documentation). Workers also alleged that Agriprocessors engaged in egregious employement practices, like failing to pay overtime. In October 2008, Agriprocessors was fined $9.99 million for various violations of state labor law by the Iowa Labor Commission.

In the meantime, PETA had been secretly recording slaughterhouse practices on the animals inside the factory and found cattle having their tracheas and esophagi being ripped out of their necks and surviving even after the ritutal slaughter. The video made headlines, prompting discussion in the Jewish community over whether such practices rendered the meat nonkosher or not. Temple Grandin was called in by PETA to testify that the slaughter practices were indeed painful for the animals. In 2006, Agriprocessors received a visit from Grandin, who said that the plant required continuous monitoring. An August 2009 article in the Kansas City Jewish Chronicle notes that the company is now under completely new management and quotes Lindsay Rajt of PETA stating that the organisation would be monitoring the slaughterhouse practices and supporting Grandin’s recommendation to have video cameras installed.

The raid spotlighted the Agriprocessors’s labor infractions as well as the issues with slaughter processes. For many Jewish activists, the incident was especially fraught because of the tradition of tying ethics standards to the requirements of kashrut. A Jewish Daily Forward piece written shortly after the raid quotes Rabbi Morris Allen, director of the Hechsher Tzedek Commission: “For too long, we’ve ignored that production of kosher food has taken place in a world where we’re concerned about the ritual aspects of food preparation and not the ethical considerations.”

Yet, such concerns appear to not have affected either Temple Grandin or PETA, whose attention to the slaughtering practices appears in a vacuum. Indeed, what is peculiar about Grandin’s writing about agribusiness in Animals in Translation is that she has nothing to say about the human labour conditions in an industry that depends so much on undocumented labour. The only time that she mentions the undocumented is when she refers to Mexicans who enter the country undetected because they are able to conceal themselves among herds of Brahmin bulls. According to Grandin, the bulls’ fierce horns and large humps make them intimidating creatures and enforcement officers are reluctant to go too near them. The point of the story is simply to point out how fearsome the bulls are.

Temple Grandin was brought in to the slaughterhouse to oversee killing practices, and it could be argued that she has a right to stay focused on only that aspect of the business. But it could also be argued that neither Grandin nor her supporters at PETA nor the owners of companies like Agriprocessors can afford to connect the ethical treatment of animals to the ethical treatment of the workers. To do so would require a fundamental shifting of the industry, at a cost that is unsustainable to all concerned. To Temple Grandin, all that matters is the overlaying of affect onto animals and her use of affect is what structures and sustains the most unsustainable form of animal and human exploitation.

V. Invisible Renderings: Animals and Capitalism

A little-known fact about the physical history of cinema is that photography and film stock is coated with gelatin. As Nicole Shukin writes in Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times, “gelatin binds light-sensitive agents to a base so that images can materialize.” Even today, gelatine remains indispensable in the production of film stock. Shukin makes note of this curious bit of visual history in order to make a point that runs through the book: Capitalism is shot through and through with such material remnants of animal life, even as it seeks to make them invisible in order to sustain the popular fiction that modern life is divorced from what Shukin terms animal capital.

A little-known fact about the physical history of cinema is that photography and film stock is coated with gelatin. As Nicole Shukin writes in Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times, “gelatin binds light-sensitive agents to a base so that images can materialize.” Even today, gelatine remains indispensable in the production of film stock. Shukin makes note of this curious bit of visual history in order to make a point that runs through the book: Capitalism is shot through and through with such material remnants of animal life, even as it seeks to make them invisible in order to sustain the popular fiction that modern life is divorced from what Shukin terms animal capital.

Shukin, a Canadian academic currently housed at the University of Victoria, British Columbia, has written a work that bears the hallmarks of a dissertation turned into a book, such as the need to restlessly cite various theoretical sources in order to legitimise its own forms of inquiry. Nevertheless, Animal Capital is a profoundly important book that offers some searing insights into the ways that animals have been rendered creatures of sentiment, instinct, and affect even as their presence enables the spread of neoliberalism.

We live in a time when we are constantly told that the only sustainable way to live is to constantly recycle and use our resources to their maximum effect. The rendering industry takes this logic of reuse to the world of slaughterhouses. In the home kitchen, rendering is the simple process of turning fatty animal tissue into a purer fat, as in the making of duck confit. On an industrial level, rendering involves turning the unwanted and inedible leftovers of animals into products as varied as soap (from tallow) or cat food. Rendering has long been valorised as the meat industry’s built-in mechanism for ensuring that nothing is wasted in a kind of ecological service to society and as a corrective to more wasteful forms of industrialisation. But as Shukin points out, “More than just mopping up after capital has made a killing, the rendering industry promises the possibility of an infinite resubjection (“return”) of nature to capital. The “industrial ecology” metaphor of the closed loop valorizes the ecological soundness of waste recovery and recycling just as the rendering industry effectively opens up a renewable resource frontier for capitalism.”

We may at first be hard-pressed to find a reason to critique rendering which, after all, seems to provide a way to use up the surplus generated by capital in the literal mounds of offal it throw out. But the problem with such an uncritical view of rendering is the same as the problem with Temple Grandin’s myopic view of the livestock industry. In focusing so narrowly on only creating “humane” practices of killing, Grandin and her ilk leave unchecked the many dangerous effects on both human and animal consumers and labor. Similarly, believing that the rendering industry is some form of good and innocent capitalism allows us to forget that we should not be overproducing meat in the first place.

Animal Capital offers a way out of the morass of affect left us by the likes of Grandin. Yet, Shukin’s work also offers a significant departure in the reading of capital that may not sit well with some: It decentralises the “privileged figure of the laborer…as the focal historical subject of industrial capitalism.” Shukin’s central questions are: How do animals enable and make capitalism perform better even as their presence is literally and metaphoricall and violently erased? What can we regain in our understanding of how capitalism works when we place animals at the center of an analysis? To answer these questions, she returns us to the primal scenes of capitalism which, it turns out, were interpenetrated with animal life from the start – the use of gelatin on film being only one example.

Henry Ford’s assembly-line production in Dearborn, Michigan is routinely credited – or blamed – for the birth of Fordism. However, Ford in fact designed his automobile production methods after watching the moving lines in the “vertical abattoirs of Cincinnati and Chicago, with deadly efficiency and deadly effect.” Similarly, in Chicago and New York City, former meat markets are transformed into trendy neighbourhoods. All around us, animals penetrate capital.

Where Grandin uses affect to locate and keep animals in their place (if we could just think like them, we could end their suffering, right before killing them in vast numbers), Shukin points out that affect is ruinous. She repeats the question posed by Donna Harawy in Primate Visions: Gender, Race and Nature in the World of Modern Science: “What forms does love of nature take in particular historical contexts? For whom and at what cost?” Animal Capital is thus critical of the modern rush to endlessly engage the logic of vanishing as in the oft-repeated and plaintive cry of an ecological movement that insists that all modern life is built upon the disappearance of species and even humans from the face of the earth. Much of this is true, but the sentimentality and affect through which this discourse appears to us is wrapped around notions of authentic “other” (non-white) cultures and species that could be lost to us if we (white) saviours do not rush to their rescue.

Shukin produces a telling genealogy of animals within capitalism, showing how they are still deployed within its vectors, and she persuades us to dismantle the far easier idea that technology and animals only existed together in a far-away and pre-industrial time.

What then, of the animals themselves? Shukin gestures towards the possibility of animal agency, but acknowledges that there are few ways to judge the existence of such: “… the rendering of animal capital is surely first contested by animals themselves, who neither “live unhistorically” nor live with the historical passivity regularly attributed to them.” For that, we have to turn to present-time incarnations of animal eruptions.

VI. Animal Eruptions: Or, When Dogs and Whales Go “Wild”

On February 24, 2010, a killer whale named Tilikum attacked and killed a trainer at Sea World. The incident sent shock waves through those long accustomed to seeing the giant creatures cavort and play tricks for the benefit of spectators. As the story unfolded, details emerged that made it seem like that Tilikum was a repeat criminal offender. The same whale was blamed for killing a trainer who lost her balance and fell in the pool in 1991 at Sealand of the Pacific in Victoria, British Columbia. Tilikum was also implicated in a 1999 death, when he was found floating with the body of a man draped over his back.

Recent weeks have seen reports of packs of Beagles in Long Island going on seemingly mindless and deeply feral attack raids on humans and their more timid domestic dog partners. The problem here is man-made: Hunters buy the animals to aid them in the hunting of rabbits, and the dogs that don’t make the cut are simply dumped in the wild. Left on their own, their apparently revert to a feral state. Recently, a woman reported that she was walking her retriever when she found herself hounded down by a pack of 4-5 Beagles.

Snoopy, it seems, has gone native.

Whales and dogs are subject, like so many other animals, to the affective fictions we construct around them. We convince ourselves that putting a giant whale in an enclosed space and teaching it tricks means that we have established a loving relationship with the entire species. Dolphins, we tell our children, are eternally smiling at us when in fact their mouths are simply naturally upturned. Elephants sway their heads from side in their enclosures, and we convince ourselves that they are listening to some ethereal music when in fact the gesture simply means that they are slowly going mad in their cramped and unnatural habitats.

When animals explode and turn upon us, we are left with no more affect with which to sustain the myth that we have formed a deep and connective bond with them. To save ourselves from further disillusionment, we retreat into our archive of animal criminality. While we may no longer hang sows for murder, we do not hesitate to invoke the past record of a killer whale and subtly indict him for the possession of a murderous character. All the while, we use animals to further and legitimate our exploitation of them.

Dracula may vanish and turn into a bat, animal fat may be rendered reusable by capital, and we may turn all conceivable creatures into our pets. We might memorialise a dead and semi-feral dog and render her into a beloved icon, but are we really prepared for the consequences of sustaining our affective fictions about animals as our companions and cohabitants? How do we end the ways in which we use that affect to sustain the exploitation of capitalism?

***

For more on affect and neoliberalism, see also “What’s Left of Queer: Immigration, Sexuality, and Affect in a Neoliberal World.”

For more on animals, see also “Racism and the American Pit Bull.”

Originally published in No More Potlucks, Number 8.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.