If you’re going to be a working writer or any kind of “creative professional,” demand the same kind of respect you would give to someone who fixes your plumbing.

This is my response to the critiques of my earlier piece, “Scab: Academics and Others Who Write for Free“

In his response to my work on scabs, Evan Kindley insists that I’m demonising “writers, editors, and publishers for making and publishers for making compromises in the service of ideals other than a perfectly regulated labor market.” As one of my twitter pals pointed out, I’m hardly demonising anyone especially since, as a working writer, I frequently make my own compromises. Rather, I’m pointing out the flaws in a system that demands we make those compromises. This is why I consistently point out the flaws with the seductive logic of love, one of the chief engines of neoliberalism.

Kindley’s biggest problem is that he can’t or won’t recognise what what he repeatedly and unironically calls, “something called neoliberalism.” I’m not going to engage his work on that ground: I’ve long grown tired of the idea, so prevalent among some, that neoliberalism can’t exist because Marx never used the word, or because they simply can’t recognise its many insidious forms. But his piece is emblematic of a range of critiques of my pieces on writers as scabs, and I find it a useful way to engage my own response.

The larger point of my book project, Strange Love, is that the affective labour and discourse around neoliberalism are what allow “social justice” movements (and the left publishing world) to replicate and rebuild disastrous economic policies. It’s phrases like “labour of love” that serve as the engine of neoliberalism.

Kindley can’t and won’t dislodge the logic of the labour of love, preferring to believe that there is a world where people can and should work for free because they “make compromises for what they love.”

To engage this further, he expounds upon the history of the “little magazine,” but lumps together several disparate entities under that rubric: Jacobin, The Rumpus, The New Inquiry, the Los Angeles Review of Books (LARB), n+1, and Avidly, and claims that they “have managed to evade or short-circuit the established journalistic market,” writing that “[w]ithout these outlets, these radical or unconventional pieces simply wouldn’t be written,” and effectively lumps these with both The Awl, and In These Times.

But, in fact, all of these operate differently, reflecting both the kinds of work they can produce, as well as their overall quality. To start with his claim that these are brave publications putting out work no one else would publish: In fact, as I’ve pointed out here, Jacobin did exactly the opposite, refusing my piece because it was “ultra-left.” The New Inquiry was the site of my most horrific editorial experience so far, so searingly bad that it will be immortalised in my anti-memoir. In contrast, The Awl and In These Times are professionally run and have excellent editorial staff, including fact-checkers and proof-readers.

All of this makes a difference, because it’s not just that money should be poured into a publication (all of these publications ask for and get money, in varying amounts, a fact that Kindley also ignores), but that its raft of editors should have the necessary experience to not only commission pieces but shepherd them from beginning to end with integrity to both their writers and readers; this means producing work that’s provocative and interesting and actually challenges the latter.

How are writers who are barely making it supposed to toil away at truly innovative work that challenges the status quo, work which actually requires forensic and not merely diagnostic analysis? How are editors, who lack both the editing experience and any real understanding of what it takes to run an actual magazine and not just a fun blog, supposed to commission or work with people who might have the skill and experience to write those pieces?

Take a look at the pages of, say, The New Inquiry and Jacobin. There’s some rare good work in there, but I challenge anyone to find too many pieces that are more than interesting thought pieces or analysis (or, at best, brief history lessons). Chomsky’s recent piece in the latter, for instance, was also widely reproduced elsewhere. Without either the funds or the expertise, such publications serve as little more than mouthpieces for graduate students producing work that builds upon their graduate studies or the work of professors or activists with secure positions.

Writers who can afford to produce such work for free are steeped in massive privilege in comparison to the writers who only write for a living. That stability, that guarantee of a steady income from work that’s paid well, would make a huge difference to writers who must patch together rent, groceries and every other expense from nothing but writing gigs. The solution to this untenable situation is not that every writer should become an adjunct or a professor, but that every writer should be paid well when he or she produces work.

Which brings me to the space from which Kindley writes, a space of relative privilege but also of a nostalgic imagining of a world where the “labour of love” is to be excused and rationalised as somehow being outside of capitalism itself.

I don’t generally think of who or what people are as I interrogate their points, but it has been my very considerable experience that, when it comes to the matter of writers as scabs, it’s worth asking who makes the criticisms of my argument because it always reveals a lot about the structures they support.

I have Kindley’s explicit permission to reproduce his responses to my questions about what he does for a living, and they were what I expected: that he “used to edit for LARB, and was paid for doing so, but not a lot (at the peak it was a reasonable part-time salary, but not enough to live on).” He continued, “I left in January 2014 to focus on my own writing and teaching. For the past two and a half years I’ve also been employed as an adjunct professor at [College X]. So, before I decided to leave, my living was cobbled together from teaching, freelance writing, and editing.” I’ve left out the name of the institution which currently hires him as an adjunct; that was my decision, in order to protect his privacy. Kindley also acknowledged that he makes his living almost entirely from his adjunct job.

I stress Kindley’s particular situation because who he is and the position from which he launches his criticism fully illustrate the situations I discuss in my original piece.

I’ll leave my and Kindley’s readers to simply return to my piece, with perhaps a greater understanding about the points I make about the caste system at play in the publishing world and the problems with free/underpaid writing.

Kindley’s response proves my larger point about the seduction of neoliberalism, when he rationalises magazines that ask for and get subscriptions as somehow being entitled to use none or very little of that money for writers, whose labour is all that actually makes them worth subscribing to (he quietly avoids my points about non-profits like openDemocracy). In addition, his view of what academics are and what they do is overdetermined by a nostalgic idea of academia as populated by comfortably ensconced leather-elbowed professors; he ignores the drastic changes in the neoliberal university, changes I discuss clearly in my piece, changes that are in fact exemplified by his own precacity as an adjunct (he may well be supported by a partner, I have no idea, but this would in fact be a relevant matter as well, going to the heart of my point about economic privilege), but which he ignores, in keeping with his pretense that neoliberalism doesn’t exist.

And so he can’t or won’t see the his own conditions of living as emblematic of the neoliberal order. It’s not that his life proves how wrong he is, or that any but that his particular position is linked to his critique which, in turn, only proves my point about how the seductive logic of neoliberalism helps writers and publishers alike rationalise lousy or non-existent pay as necessary functions of a just world.

I have no doubt that Kindley has an excellent career ahead of him; he has the time and resources to devote to it. I also have no doubt that his allies and friends, and/or as well as those who want to deflect attention from my economic critiques, will respond angrily that he has no real privilege or will provide more life details to counteract my points.

But let me emphasise, again: it’s not Evan Kindley who interests me, but what he represents: a peculiar and particular constellation of affective responses and blindnesses to the realities of neoliberalism, and a widespread and wilful refuse to consider its materiality in everyday life.

I’m concerned about writers and readers who might fail to discern how he and others like him plane down the material realities of the publishing world into one homogenous, free-spirited mass, who might not recognise his failure to acknowledge the privileges that grant people like him the ability to publish at will (the point is not simply how much one makes, but that one makes a steady income at all), and who won’t see the harm of his erasure of the realities of neoliberalism.

To them, and to anyone genuinely concerned about the state of the publishing world, I can only repeat: Don’t give away your work for free. If you want to engage in labours of love, write your own blog, form community spaces, run a communal radio station, whatever you want to do. But if you’re going to be a working writer or any kind of “creative professional,” demand the same kind of respect you would give to someone who fixes your plumbing.

As for the word “scab” itself: I’m fully aware of its historical meaning. But let’s not all now pretend that “scab” can and only does mean one thing for all of history.

To those who disagree about my use of the term: Rather than divert attention to the word itself, address the economic conditions I’ve described and formulate at least adequate responses to the issues I’ve raised. If you persist in scab-like behaviour, like writing for free or very little while working writers desperately try to make rent, embrace the term and show the rest of us how you justify working in a way that actually enables publishers to diminish our pay.

But whatever you do, don’t be seduced and lulled by soothing lullabies about love and choice as you suckle at the tit of neoliberalism.

Further reading:

Is Your Reading Material Ethically Sourced?

“Scabs and the Seductions of Neoliberalism.”

“On Writers as Scabs, Whores, and Interns, And the Jacobin Problem.”

“Make Art! Change the World! Starve!: The Fallacy of Art as Social Justice, Part I.”

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

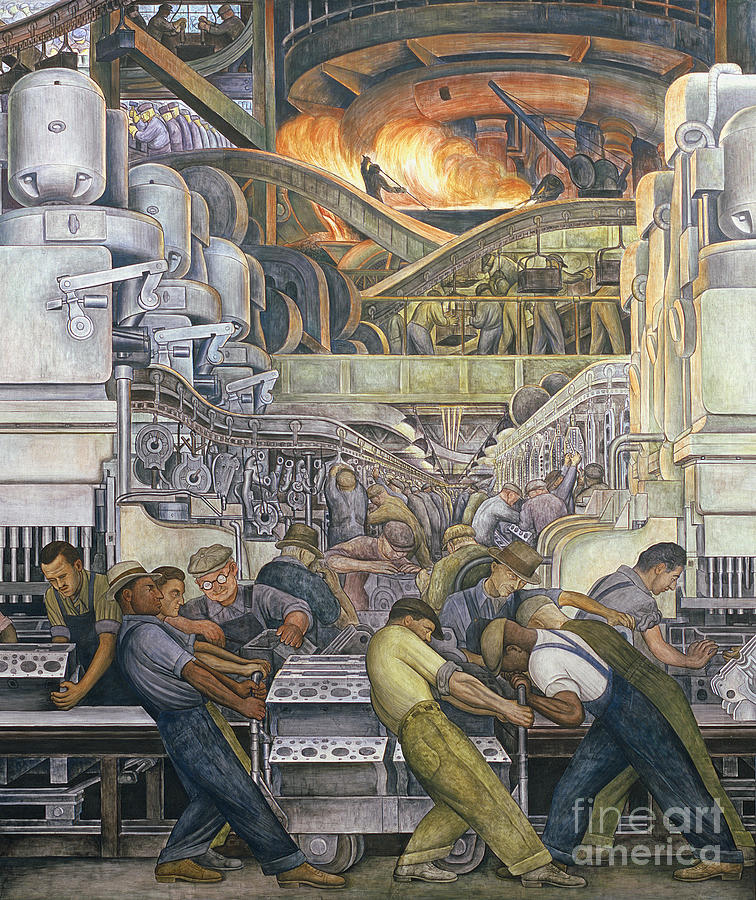

Image: Detroit Industry, North Wall, 1932-33 (fresco) by Rivera, Diego (1886-1957)