Excerpt: Those who write for free or very little simply because they can afford to are scabs.

Note [February 17, 2022]: Although they will never admit it, my constant criticisms of Guernica, Rumpus, OpenDemocracy and others have forced these publications to start paying their writers (though not nearly as much as they could). I’ll post a fuller update in the coming months. In the meantime, please remember that NOT ONE of these publications would have begun to pay of their own accord. Also, HuffPo does pay now and, again, that came about after agitation on the part of writers and my constant criticisms.

Also: I’ve responded to critiques of this piece, and my responses can be found can be found here, in “Scabs and the Seduction of Neoliberalism.”

In February, Nicholas Kristof bemoaned the fact that academics don’t write for larger audiences.

The piece was inane and sloppy, typical of Kristof’s writing, but its central thesis struck a nerve. It was subsequently critiqued by several people, including Corey Robin, who kindly pointed me out as one of those who do in fact write for non-academic audiences, but that’s not the only reason I cite his response. To the best of my knowledge, Corey’s piece is the only one which considers the issue of academic writing within the material conditions of academia today. He writes, “The problem here isn’t that typically American conceit of “culture” v. nonconformist rebel. It’s the very material pressures and constraints young academics face, long before tenure. It’s the job market. It’s the rise of adjuncts. It’s neoliberalism.”

I’ve been following these kinds of conversations about academia for a while, and watched as they’ve dovetailed with questions about writing for “the public.” Over the years, I’ve steadily embarked upon a career of freelance writing, and the bulk of my livelihood comes from writing.

So when there’s a conversation about academics writing for the public, I’m as hopeful as I am anxious and trepidatious. Hopeful, because voices like Corey’s situate such writing within the economic conditions of neoliberalism, but anxious and trepidatious because more often than not, such conversations eventually paint academia in unrealistic terms, hewing to Kristof’s wild fantasy about it as a quiet, cosy corner where the life of the mind continues unabated and untouched by trivial concerns like rent and bills. In this Shangri-La, writing for “the public,” a barely understood entity amongst most academics, is seen as an act of public service.

But the reality is that most university courses are taught by ill-paid adjuncts, and that universities are increasingly cutting tenure lines while overstaffing themselves with administrators.

Yet, the demands made on adjuncts, tenure-track, and tenured faculty have not eased up. If anything, the universities now feel they have a seemingly limitless pool of highly qualified candidates to choose from, and that has meant that getting and keeping a tenure-track job has become more onerous. It used to be that the average tenure requirement regarding publications was something like three peer-reviewed journal articles and one book; today, it’s more likely the case that you have to have a book on day one (an actual book, not just a contract for one), followed by yet another before you even ask for tenure, along with every other traditional requirement, like departmental service.

In this context, is the possibility of academics writing for wider audiences necessarily a good thing? I’ve written about the perils of academics writing, usually for nothing or very little, for mainstream publications in “On Writers as Scabs, Whores, and Interns, And the Jacobin Problem”: “The breakdown of the stability of university jobs, the dwindling prospect of tenure for many in academia, and the fact that professors are increasingly being admonished to publish in the ‘real world’ to prove that their work is ‘relevant’ has meant that publications like Jacobin are able to depend on a large number of highly educated (but not necessarily qualified) writers for whom writing is not their source of income and whose names lend a star quality.”

I want to return to a thread I introduced in that earlier piece with much greater force: That those who write for free or very little simply because they can afford to are scabs. This would include not just academics with tenured or tenure-track positions, but adjuncts, professionals (like paid activists and organisers), as well as, really, just about anyone who writes for places like Guernica, The Huffington Post, OpenDemocracy.net, and The Rumpus (and this is a very, very tiny list).*

My use of the word “scab” is often met with a range of responses from irritation to blind fury. Academics in particular, the sort who wax on about neoliberalism and its exploitation of labour, turn apoplectic as they insist that they’re not scabs but performing vital services by “choosing” to write for free.

But what is neoliberalism if not the rationalisation of capitalist exploitation under the rubric of “choice”?

The fact that writing is a sorely underpaid profession (and really, one that’s not even considered a profession by most) has to do with a complicated set of factors, and academics and others writing for free is not the only cause. But I want to focus on free writing because it is in fact a key factor and becoming pervasive in what is an increasingly frightening world for academics and would-be “public intellectuals” desperate to find a foothold (and extra income) in public discourse.

When someone offers to write for free or a negligible amount, it allows a publication to further downgrade pay scales for working writers or to even refuse to pay them at all. In the most traditional sense, a scab is someone who knowingly takes up a job that pays less than the wages that regular workers get. So, technically, yes, someone could well argue that such writers aren’t scabs at all, especially if no one gets paid at places like openDemocracy.

But if we are to consider the changes that neoliberalism has wrought, we have to reconsider how we think of the devaluation of labour across and away from stricter, older definitions of scabs and workers, and we have to consider how workplaces operate differently under neoliberalism, especially in the world of publishing which survives in print and online formats.

First of all, inevitably, someone does get paid at such places, either in cash or in cultural cachet: HuffPo has a few paid editorial positions and, more importantly, is a multi-million-dollar corporation which could actually set an example by paying its writers really, really well: it simply won’t, in order to make an obscene amount of profits. The Rumpus, the last I heard, employs at least one paid editor.

But not only does The Rumpus not pay writers, it states, “We’re interested in seeing finished essays that intersect culture. We realize it’s a lot to ask for people to write something without knowing if it will be published. On the other hand if you aren’t driven by the story so much that you have to write it then it’s probably not a good fit for The Rumpus.”

In other words: If you can’t produce work for free, it’s probably not worth producing anyway. This logic would only make sense to someone who has their head firmly in the sand of a glorious Madagascar beach where they’re on perpetual vacation, or up the ass of a very rich benefactor. To be fair to The Rumpus, literary work (like poems and fiction), which is its focus, can’t really be pitched the way, say, an investigative piece can, but that still doesn’t justify the fact that it doesn’t pay its writers.

Guernica and OpenDemocracy are both 501(c)3s. Where, in the case of the former, does that money go if they’re not paying for writers like Tariq Ali, and guest editors like Clair Messud? Their labour is provided gratis, as a symbol of their entrance into the upper echelons of the writing world.

OpenDemocracy’s funders include The Open Society, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Tides Foundation, and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. Apparently, not one of these highly reputable funders thinks it’s a problem that a publishing organisation asks for money but can’t be bothered to even pay the writers without whom it simply would not exist.

Paying for writers is no guarantee of quality, and Nicholas Kristof is evidence of that. But the long-term effects are deleterious and many. We’re losing a sense of what it really means to develop and sustain an intellectual culture. If you can’t pay for writing, you’re not going to get work that actually interrogates the status quo and will only end up rehasing the same opinions over and over again. And if you, as a reader, can’t make the connections between the conditions of exploitation that compel writers to scramble to make rent and the fact that you’re reading free material that has received no compensation, you should stop reading about the exploitation of farm workers on HuffPo.

The system of free writing has created a caste system, with those who can afford to work for free doing so while those who can’t struggling to pay the bills and often giving up. As with unpaid interns, those who can afford to write for nothing inevitably make it into networks of influence which allow them to continue on to actual paying gigs. This crucial element, of the link between economic privilege and access (and I don’t just mean rich people), is frequently erased by those who insist that it’s their free writing that eventually landed them well-paying assignments. But it’s not their free writing and “exposure” that got them their jobs; it’s their ability to survive without having to depend on writing for a livelihood that guaranteed they could continue to write for nothing.

All of this has long-term effects on the overall tenor of writing from the left. If its writers are mostly those who benefit from the exploitation of free labour, but fail to see how their free writing makes it impossible for the rest of us to actually earn our living from writing, what are the chances that they might actually be able to interrogate the full and insidious force of neoliberalism?

If you’re an academic/professional/activist who writes for free, or edits print or online publications which won’t pay their writers but prides themselves on having all the bigbigbig names write for nothing: You are part of the problem of neoliberalism. You are making it possible for publishers to refuse to pay professional writers what they’re worth. We are seeing the adjunctification of the writing world, where a false scarcity of funds allows those in power to essentially blackmail their workers: You won’t work for the measly amount we’ve offered you? Fine, I’ll just get BigNameProfessor to do the same work for free.

For those wondering what to do, the solutions are simple. If you’re any kind of a writer, demand pay, and good pay, even and especially because you don’t need it to survive. If you’re a would-be publisher who wants to provide a space for radical-feminist-whatever writing but don’t know how to do it without your pay rate starting in the hundreds, and not the measly tens: Don’t publish. It really is as simple as that. If you don’t have work for people to read, you don’t exist anyway, so what gives you the right to insist that your workers produce labour for free or nearly nothing?

Stop using phrases like “labour of love” to describe your free writing and use “unpaid labour” instead. That way, we might all start thinking about writing as labour, not as a hobby or as “writing for pleasure.” It’s exploitative to think that writing should not be a form of labour that pays well.

Don’t give up your cheque in the hope that the money might go to a freelancer: It rarely does. It’s naive to believe that the publishing world, which is largely for profit, is somehow imbued with the redistributive justice of a grassroots collective.

Think hard about the solutions you come up with. Dissent magazine does what I think it considers the honourable thing to do, by not paying academic and professionals so that it can pay its freelancers a better sum. But surely such measures also make it more likely that, in times of budget crunches, publications are more likely to opt for the writers they don’t pay for over the ones they have to compensate.

No one should be paid well just because they’re suffering or because they’re hard-working, or because they live with the world’s most adorable cat. None of those factors are in any way indications of good or great writing. But if things don’t change, and if even leftist academics and activists persist in the belief that writing is something you toss off on a Saturday morning in between brunch and laundry, we will only continue the current freefall into a neoliberal economy which extracts profits from insidious systems disguised as machineries of choice, free will, and “creative” non-work.

If you can’t see unpaid writing as part of the neoliberal machinery of affective exploitation, you should stop writing about its evils. Nothing, nothing that you ever write for free, about the problems of our time, including relentless war, the exploitation of workers, queer or trans politics, the banking system, or the prison industrial complex will ever be valid, until you confront your own role as a neoliberal. Until then, you’re just another hypocrite, like the publishers of Opendemocray and HuffPo, and just another scab.

Note: I’ve responded to critiques of this piece, and my responses can be found can be found here, in “Scabs and the Seduction of Neoliberalism.”

*Several caveats and a few additions (added before my final response):

- Sarah Kendzior has written about related issues, and you can read her piece here.

- Eric Stanley and Toshio Meronek wrote about the ways social media deploys our unpaid labour, here.

- Chris Sherman made this comment on my Facebook wall, and I think it’s worth reproducing here:

“I think this is a very important topic, and resonates far beyond writing. Tons of “content,” not just writing, but music and video as well as software is being produced more and more for free these days. I think that this raises a lot of important questions for those of us outside these industries as well.

My understanding of the term scab is that it refers to a person who does not simply work for less money, but who agrees to work during a strike. I raise this to point out what I take to be a key element of what a scab is—someone who undermines the self-organization that seeks to improve the lot of workers.

The fact that such an organization (whether a union or a less formal kind of organization) exists is very important. It’s existence signals that workers cannont be dealt with as individuals to be placed in competition against each other. It can articulate demands beside those for higher pay that would be completely outside of the power of individual workers to achieve. And importantly, such an organization can offer support, both moral and material, to workers during a strike or other labor action. It shows that workers have a common interest, and demands that their concerns not be subjugated to the exigencies of production.

I think that part of this attempt to critique unpaid work must be to address the question of organization. Without the prospect of working together in a political organization that provides a means to unite individual interests through shared struggle, I think we will be left with a moral compulsion divorced from the possibility of political action. Or at most, a form of political action that is carried out in individual isolation with little opportunity for genuine solidarity and a reduced potential to really improve our lives.

A moral compulsion to not work without pay is not inherently antagonistic to neoliberalism. In fact, I find moral compulsions that can be achieved through individual action in the marketplace to be very much consonant with the practices and ideologies of neoliberalism. Reagan and Thatcher both had strongly moral messages, which was a large part of their appeal. (Needless to say, their moral values were appalling.) I think that the fact that working for free has become such a common experience probably has more to do with the state of the economy and the devaluation of labor in general than it does with the logic of neoliberalism.

I’m certainly not so naive to think that writers can simply get together and create a union capable of addressing unpaid work. There is good reason to believe that unions as they now exist are actually not well suited to the problems contemporary workers face. And of course there are many ongoing experiments in finding a form of organization that is adequate to these problems. I think that this is a real problem that will only be addressed through a process of theorizing and struggle that will produce new forms of organization suited to contemporary challenges. You have eloquently and persuasively interrogated the problem of the compulsion to work without pay, but I think we need to add the question of political organization to the agenda.”

My response:

- Thanks to Robert Wood for reminding me that most adjuncts don’t always have the time to write for publications of any sort. I was referring to the tendency amongst adjuncts to pitch and write for free, but it bears emphasis that adjuncts are usually woefully underpaid and overworked.

- Not everything that’s online needs to be paid. I exclude blog outlets where no one is paid, or blogs that are off-the-cuff and not fleshed-out, researched pieces, as well as community-driven outlets that are not specifically meant to create profits. I also want to acknowledge that I’m hardly insulated from the pressures of writing for free, having allowed Jezebel, for instance, to reproduce a blog piece of mine. My hope here is that we can all begin to ask hard questions of each other and gain a measure of clarity on these matters.

- This piece is not about academics writing for professional journals; that’s an entirely different topic, to be tackled at another time.

Note: I’ve responded to critiques of this piece, and my responses can be found can be found here, in “Scabs and the Seduction of Neoliberalism.”

You can read more of my work on the issue of writers, pay, and neoliberalism in these other pieces.

- “Jacobinned: The Story Behind the Story Jacobin Refused to Publish.”

- “Undocumented: How an Identity Ended a Movement.“

- “Is Your Reading Material Ethically Sourced?”

- “Scabs: Academics and Others Who Write for Free.”

- “Scabs and the Seductions of Neoliberalism.”

- “On Writers as Scabs, Whores, and Interns, And the Jacobin Problem.”

- “Make Art! Change the World! Starve!: The Fallacy of Art as Social Justice, Part I.”

- I’m a Freelance Writer. I Refuse to Work for Free.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

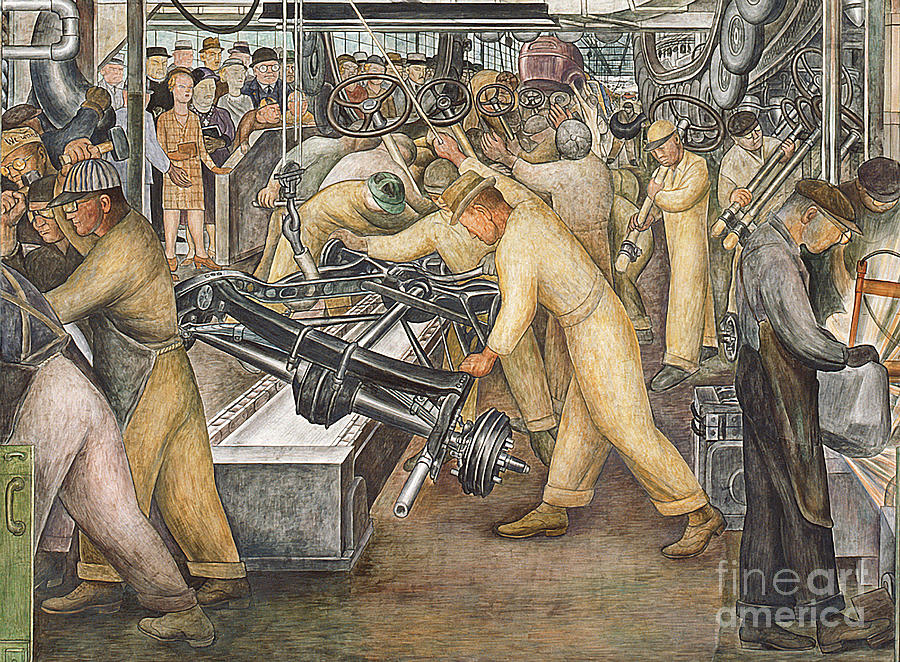

Image: South Wall of a Mural depicting Detroit Industry, 1932-33 (fresco) by Diego Rivera