Call me a classicist, but years of reading novels tells me when something is off.

The woman’s name was Kerstin, and that was, at first, all the doctors at Landesklinikum Amstetten hospital in the Austrian town of Amstettenwas knew about her.

She was brought into the emergency room with life-threatening kidney failure by Josef Fritzl, in April 2008. He arrived with a note he claimed was from her mother, but there were too many details that proved puzzling, and matters were turned over to the police a few days later. Subsequently, the case file on Fritzl’s missing daughter Elisabeth was re-opened — he had long claimed that she had run away twenty-four years ago to join a cult.

The story that swiftly unfolded could be the premise of a horror movie. Fritzl had imprisoned Elisabeth in the basement of the house he occupied with his wife, her mother. Over the course of many years, he repeatedly raped his daughter and she gave birth to seven children. Not all of them survived. Of those who did, three were taken upstairs and raised by the elder Fritzls — the wife Rosemarie apparently had no trouble believing that her husband just happened to keep finding lost children on their doorstep and even social service agencies believed his stories.

Rosemarie Fritzl claimed to never suspect anything for twenty-four years, even as her husband set about “secretly” expanding the basement to accommodate a large family, never allowed her to come downstairs, and even as tenants said they occasionally heard noises, even as seven children were birthed so close to them.

There is a horror in this alone, that a woman who had to have known — please, let us not argue about that — could so blithely go through life knowing full well that her husband led some sort of a double life, that that life may well have involved her own child who was raped constantly and forced to give birth to her grandchildren under her own roof. Did she sometimes hear the cries and the screams and pretend all that was simply the wind outside?

But horror and suspense — genres I love — so rarely work with the material of our actual lives. Indeed, how might we render the story of the Fritzls in a way that distills the essential vileness of what transpired? I don’t mean the incest itself, which is bad enough, but the horrific ways in which an entire family and its neighbours and town appeared to have conspired and colluded in closing all eyes to the reality of what they had to have suspected. One of the claimed “found” children was Monika, who appeared in a stroller at the age of ten. Surely Monika, unless so badly abused as to be incapable of communication, had to have revealed something of where she came from.

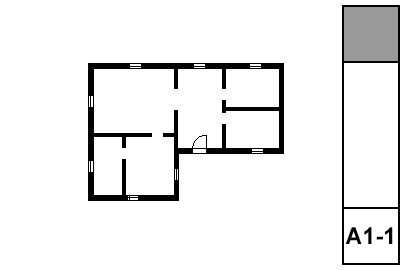

Emma Donoghue’s 2010 novel, Room is loosely based on the Fritzl case. It strips the novel of the murkier elements of what happened in Austria and instead presents a story about a young woman kidnapped and held captive in a stranger’s tool shed for seven years. Raped repeatedly, she gives birth to a son, Jack, to whom she determinedly teaches the alphabet. He grows to be five, a smart and intuitive child with a prodigious vocabulary for his age who has never known the world outside the eleven by eleven space. But he is close to his mother, whom he calls Ma, and understands the urgency of the escape plan she hatches for him one day. Roughly half of Room is about their lives after freedom — Jack learns to walk down stairs, and the two have to begin to bond as mother and child outside of the intense closeness foisted upon them by their captor.

Room was a hugely successful novel, commercially and critically, making it to both the Booker prize shortlist and the New York Times bestseller list. But when I read it, I was left unimpressed. As I pointed out in my review at the time, it was “more gimmicky than engrossing; there’s not much beyond the fact that a child narrates it.” I concluded that “this is a book you might read to see the effect of Donoghue’s craft, but it’s not likely to be a book you return to.”

To me, Room felt, well, too scripted. Everything about the novel signaled that it was written for another purpose; it was too self-congratulatory about its success in having convey so much through a child’s eyes. It seemed to revel in its sense of craftsmanship in much the same way that Meryl Streep’s performances rarely involve her actually inhabiting her characters but, instead, are more about showing off how well she can “do” accents or convey meanings with mere glances. There are always invisible arrows pointing to her “craft” as an actor; we’re never allowed to forget that it is Meryl Streep acting. Similarly, Room continually gestured to how well it was doing as a novel.

Room was finally made into a successful movie — Brie Larson received an Oscar for an excellent performance as Ma. I was surprised at how much I liked it. It is gripping, for a film that is after all simply about a room and what happens when people leave it. Every performance here is excellent without distracting us from the kernel of the story, the shift from claustrophobic numbness to the shock of the everyday visited anew by Ma and for the first time by Jack, who needs sunglasses and masks to cope with the sun and a whole world of new germs.

Room the movie works as well as it does because it was a great screenplay to begin with, as Room the novel. Everything about the book that bothered me is in fact perfect for a narrative that works well as a cinematic rendition. In the novel, Donoghue goes to great lengths to point to the minute elements of the room, and it’s hard to escape the feeling that she wants you to notice and be awestruck by her attention to detail. There was even an accompanying website that showed you the room, effectively bringing it to life. Call me a classicist, but that struck me as something that contravened the implicit contract between an author and a reader: I shouldn’t need an illustrated guide to what should be evoked for me in the novel.

As it turns out, one of the mini-documentaries on the DVD of the film has Donoghue herself saying, with some pride, that she envisioned the novel as a film long before she was done writing it. Call me a classicist, but years of reading novels tells me when something is off.

About the Fritzls: there is a somewhat grim update. The various members of the family are coping, some better than others, with their shocking pasts aided, it seems, by the kind of excellent medical care we would do well to emulate. But the house itself, where all that horror took place? The basement has been filled with concrete but there have been no buyers, as of late last year. In September 2015, it was offered to asylum seekers. In some ways, the horror continues or, perhaps, who knows, is abated somewhat.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.