From the Detroit News comes this bit of news: PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) has waded, as it were, into the Detroit water crisis. It has offered to pay the water bills of ten residents of the city if they agree to go vegan for a month.

I’ve had mixed feelings about PETA for a long time. In 2007, I interviewed its Vice President, Dan Mathews for Windy City Times. He’d just published his memoir, Committed: A Rabble-Rouser’s Memoir, which I liked, and what occurred to me at the time is that in many ways PETA is one of the last formal organisations committed to forms of direct action, reminiscent of ACT UP. Say what you will about the classic PETA actions, like throwing paint on fur coats, but there aren’t a lot of groups able and willing to go to that extent.

Granted, any group comprised largely of people of colour or fighting for issues other than that of animal rights/welfare would have been shut down almost at its inception and its members thrown into prison for eternity. There’s a long and complex history to be written about PETA’s history in a country which often seems to care more about the animals left behind in hurricanes than the people whose lives are devastated, and where a tradition of omnivorous meat-eating sits alongside another of intense pet ownership. There’s also a history of the racialisation of animals as property and pets which, set alongside the history of the animal rights movement, provides a different picture altogether of what we think we know about the history of American domesticity.

I write about animals, and my forthcoming work looks at the affective power of “animal rights,” a term and a field I’m suspicious of even as I reluctantly describe myself, on occasion, as an “animal lover.” But I also write about capitalism and neoliberalism in particular, so it’s hard for me to look at PETA’s latest move and not be repulsed by the degree of its insensitivity and callousness.

The fact that Detroit’s water crisis comes as the end product of a long set of privatisation policies which disproportionately affect Black and poor populations hasn’t escaped notice. PETA’s proposal is callous, short-sighted, and ultimately meaningless. It does nothing to advance veganism or to get people to think about the systemic links between, say, poverty, race, and the degradation of animals, for meat or pleasure. Worst of all, it treats poor people as those deserving of economic relief only if they adhere to often unreasonable standards determined by mostly well-off, clueless, and usually white people.

Their official statement makes it clear that PETA doesn’t really give a damn about the larger problem, and studiously avoids making any political statement about the situation. It ignores the fact that meat and meat products are sometimes cheaper to procure and prepare than a vegetable-based diet, and it offers no clues as to how to make a vegan diet more sustainable for people living on the edge. Each family is offered a basket – an entire basket! – of “healthy vegan foods and recipes.”

If PETA gave a damn about Detroit’s suffering residents, it would simply commit to feeding entire families, even if for a period of time, with no conditions. And it would do so not simply with a spiel about why veganism is best for everyone, but with a thoughtful and considered statement about the links between poverty, diet, water, and the environment.

Instead, it does what banks and other opportunistic entities have always done to the poor and disenfranchised, and takes advantage of their vulnerability. You want food? Accept our terms or else! Go vegan! You’ll be so much healthier for it! Never mind your other bills and expenses!

This is an ugly, vile, and ultimately meaningless gesture. It cements the already unfortunate and often undeserved reputation that vegans have, of being mostly clueless and mostly white people, and it makes veganism and vegetarianism seem like the privileged hobbies of a few. It positions the needs and concerns of animals opposite those of humans and, in effect, privileges the former.

But surely the real work lies in us continuously examining and contesting the ways in which animals and humans are pitted against each other in scenarios that only end in ecological disasters. If we are to begin thinking about and ending cruelty to animals, we need to ask how our economic and cultural structures enable us to be as cruel, even if in different ways, to humans. Telling poor people that they need to figure out a way to go vegan for a month in an environment that’s hostile to their very existence and where they are struggling to stay afloat is thoughtless and cruel.

Perhaps PETA should work on a new slogan: Free the Animals, Hurt the Humans.

(1) As I know too well, having cooked a lot with my vegan friend Ryan Conrad, it’s not true that vegan or vegetarian diets are more expensive, but they can be difficult to access in a system that usually makes fruits and vegetables impossible. And as Diana Salles points out on my Facebook wall, “Meat is costly to store and prepare, goes bad quickly unless filled with sulfites and the cheap cuts are pretty unhealthy.”

See also:

My Nostalgia Trap podcast conversation with David Parsons, about “Aping Revolution.”

My interview with PETA’s Dan Matthews.

My review of Matthews’s memoir, Committed.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

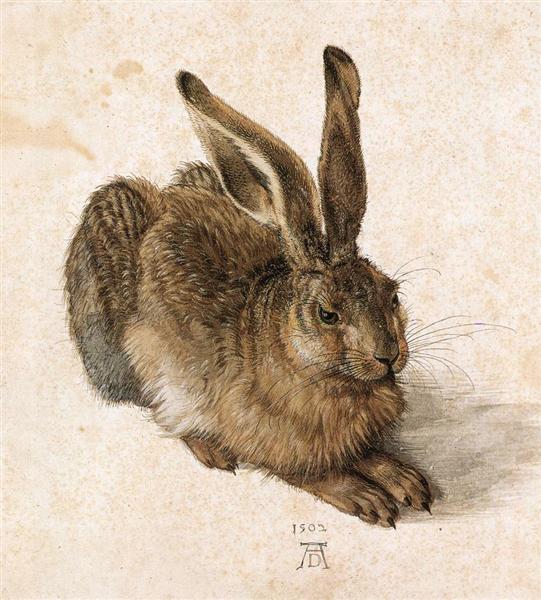

Image: Young Hare, Albrecht Durer, 1502