A person is a universe.

For Liz

In Vertigo, Alfred Hitchcock’s classic tale of memory, confabulation, and desire, Madeline, played by Kim Novak, is taken by John Ferguson (James Stewart) to see giant Sequoia Redwood trees, over two thousand years old, “the oldest living things.” Nearby, there is a large cross-section of a felled Redwood, propped up so visitors can view its internal structure. Here, each ring signifies an age witnessed by the tree, and white markers and arrows denote exact dates: “1066, Battle of Hastings,” “1492, Discovery of America” and so on. Madeline places her finger on one spot and intones, “When, here I was born.” Moving her finger only slightly, she says, “And here I died. It was only a moment for you; you took no notice.”

A little while later, Madeline will seem to fall to her death, making her words hauntingly prescient. The tree sequence makes a point that’s relentlessly pounded into us, especially in an age of intense eco-awareness: that we are but tiny blips in the march of time, that the lives we hold in such importance are in fact ultimately inconsequential.

But of course, they’re not. To John Ferguson, Madeline’s life is everything—too much, as we learn. It’s our capacity to take in the enormity of other lives and our sometimes sad but never fruitless attempts to absorb them into our own, our selves opening up to devour the lives of others like Saturn devouring his child or an anaconda widening its jaw to swallow its prey, that makes us so weirdly human. This isn’t to say that the more solitary among us are aberrations—but that most of us are in one way or another acculturated to dissolve into others or to form some kind of dissolving, a dissolution even, a dissolving of ourselves. The lines blur so.

When the Pandemic first hit, the first words meant to calm us down were that it mostly affected the old.

Some drove home the point even more brutally: the Pandemic was not as serious as we might imagine because, after all, it would simply take those whose lives were meaningless and worthless. After all, the logic went, they’d lived enough, and we could let them go. Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick declared that “hundreds” (none of whom were to be found) of the elderly had written to tell him they’d be happy to sacrifice their lives and take up jobs to save their grandchildren and restart the economy.

This sentiment, that the old should just die off to save the rest of us, or that their deaths simply don’t matter, was echoed even in places like India, where people like to yammer on endlessly about how “Indian culture” (a nebulous thing defined mostly by fundamentalists like Modi to serve the ends of Hindutva ideology) affords a place for the elderly because, supposedly, Indians revere their elders. The truth is that vast numbers of older Indians are left without care or concern, usually in the private residences of their children where they’re often relegated to the worst quarters, if that, and often abused and turned into unpaid domestic help. There’s a long and sordid and largely unexamined history of Indian immigrants in the United States importing their parents to serve as caretakers for their children. In these cases, Indian grandparents are wrenched from their homes and communities, brought to a jarringly new country with few resources of their own, often unfamiliar with the language or customs of their new habitats and made to perform unpaid labour, all under the guise of “family unity” or whatever rubbish rationales their children might spout to curious neighbours and friends. It doesn’t help that so many on the radical left like to go on about “elders” as mythic, revered, desexualised creatures whose only purpose in life is to rot into sexless bodies endlessly wiping tears and shit off their grandchildren’s bodies.

It’s not just the “East,” of course. In North America, conditions for the elderly are often shockingly brutal. A Chicago friend once remarked that loneliness was the best thing that could affect elderly parents, given the levels of negligence in so many assisted living homes. In Quebec—Quebec—a third of the Covid-19 deaths so far have come about in just six long-term care and seniors’ residences. At CHSLD Herron, a privately-run senior residence, officials walked in to find that elder residents had essentially been abandoned, “left unfed and untended to, with full diapers and soiled beds.”

The old, everywhere, are seen as dispensable, dry husks and carcasses even when they still live and breathe, their memories and entire lives deemed unworthy of memory and regard. If we don’t kill them from neglect, we fetishise them to death with a lot of useless patter about “revering” them, as if they’re idols we place in strategic corners of our houses rather than living, vital beings.

Our idea that life itself is merely a tick-tock in time has everything to do with our insistence that we are nothing in the universe, and this in turn affects how we think of the “elderly” (however we construe that term).

But we might consider this: that a person is a universe, of multiple lives, of endless dreams, of hopes realised or dashed or both, of travels and abandon, of yearning and longing and lust and madness and anger and rage and love. A person is a universe, standing in a street in Paris and drinking it all in for the first time. A person is a universe, teaching Spanish to a child she sees as sad but full of potential, befriending her for life. A person is a universe, driving through the desert at midnight to get to the Grand Canyon.

A person is a universe.

***

For more in this “Pandemic” series, click on this category.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

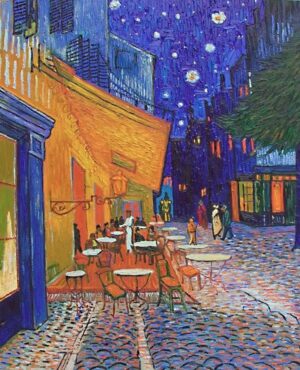

Image: Café Terrace at Night, Vincent Van Gogh, 1888.