For me, there’s a link between the brute reality of Tamas (as I recall it, and there is some irony in that) and the sugary puffiness of Patty Duke: the connective tissue between what we imagine, what we know, what we wish we knew, and what we would like to imagine.

Patty Duke is dead at the age of 69.

Duke had been what we used to call a “child star,” back when the word “star” meant a studio-controlled entity carefully manufactured to live up to a particular image. She was also a child star who, according to her, had been cruelly used and abused by her managers John and Ethel Ross. It’s a sign of those times that they changed her name from Anna Marie to “Patty” because they deemed the former too “ethnic.”

Duke was never a great actor but that’s a view in hindsight, given how much our ideas of what “acting” should look like have changed. Her over-the-top work as Helen Keller in The Miracle Worker gained her an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. Later, her acting ability would be mined for in The Patty Duke Show, where she famously played twin cousins.

I’d never heard of the show till I moved to the United States in 1989 for graduate school. For a brief while, I lived in an apartment on the top floor of a house near campus. I shared it with a roommate, and we set up our television set in the living room. To my delight, the cable subscription of the previous renters had never been cancelled because of some technical snafu. What I found most riveting — well, besides the endless commercials for Ginsu knives — was the parade of vintage television shows on one of those nostalgia channels, perhaps Nick at Night, Patty Duke among them.

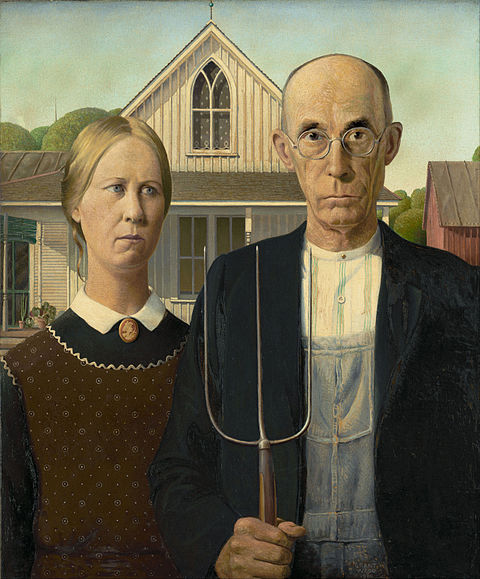

It was here that I first came into contact with what I think of as the American reservoir of invented memory, that seemingly endless bounty of old-timey memories that are profoundly fictional and rooted in a nostalgia for times that never really existed. I hadn’t grown up in the States and I was living in a state, Indiana, which resolutely clung to the idea of itself as the “heartland.” I’d like to tell you that I witnessed — there is no other word for it — the entire stream of older American television with an air of amused condescension and knowing wit, and that may well have come in later years (and it would not be something to be proud of). But, really, for the most part, I was simply riveted and to this day, even a glimpse of a show playing somewhere, like The Donna Reed Show or The Andy Griffith Show brings back memories and a realisation that I know exactly how the episode ends.

American television has, for better or for worse, influenced television styles and narratives elsewhere and that is especially evident today, with reality shows popping up in India, for instance. But television has also always been culture-specific. I spent part of my childhood in the early 70s in Kathmandu, Nepal where there was no television at the time. We moved to Bombay, and what thrilled me most was the prospect of this thing called “TV” that I would see for the first time. We moved into our flat, and the television set was brought in soon after. I jumped up at it in excitement and accidentally hit it with my head. The cut left a scar and a gap in my left eyebrow which remains to this day.

At least, that is the Legend of My Eyebrow as I recall it. Many years later, I would study and theorise film and television, and would be even prouder of my “TV scar.”

In the years that followed, as we moved from Bombay to Calcutta, Indian television went from being available in only a few cities to a multi-channel entity. I left India for the last time in 1994, just before neoliberalism reached its shores with ferocity. I haven’t been back since then but I know from afar that the television and media landscape there is vastly different now, in some ways more multifarious than what we have in the States, given the enormous range in regional differences. Which is to say, I haven’t a clue as to what television in India really looks like right now.

But here is what I remember about television in India: There were, at best, three channels at one time. And the first large-scale television series were based on the Hindu epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. These were … epic, in more ways than one. Over the years, television producers sought to bring socially relevant topics to what was referred to as the small screen, in a country where television viewing was still a collective experience in most families and where programmes had to be watched at the time of broadcast. In 1988, Doordarshan, the national television channel, broadcast Tamas (Darkness), directed by Govind Nihalani. This was a mini-series about Partition, and the entire country sat riveted every Saturday night, for weeks. I haven’t watched it since then but I recall it being a sober, realistic look at a part of Indian and Pakistani history that few had tackled until then. Tamas created some controversy at the time and has since gone on to being lauded as a critical part of Indian television and film history.

Television has always been part of the invention of national history, and it has also worked to clarify what the “national” means with an immediacy, at least in terms of timing, that film can never have. I’m still riveted by shows like Patty Duke. The fact that Duke was so badly mistreated by her managers and then went on to a life of turmoil until finally diagnosed as bipolar lends a shadow to the viewing but it doesn’t stop me from enjoying the show, even with a critical lens. It’s easy to dismiss Duke — and Griffith and Reed and others — as part of an invention of American life that bore no resemblance to reality and demonstrated archaic conventions, even at the time. For me, there’s a link between the brute reality of Tamas (as I recall it, and there is some irony in that) and the sugary puffiness of Patty Duke: the connective tissue between what we imagine, what we know, what we wish we knew, and what we would like to imagine.

Television has always been about the creation or at least the mediation of what it means to be “us,” even as we now barely know who the “us” really is. Or, really, given how much the form has now shifted, even as we barely know what “television” is.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.