An audio recording of this post is here.

I was just reading A Certain Writer. This person is extremely disgruntled and feels that no one really appreciates their work, and they have often said that various forces have kept them from achieving their grand potential (by which, I think, they mean a million-dollar advance and little else). We’ve all been there, so I’m inclined to be sympathetic — I mean, let’s face it, in a publishing world where the only people getting writing gigs are all 23 years old and graduates of the exact same high school somewhere in Manhattan, and where writers are constantly either backstabbing or filching from other writers, it’s hard not to feel the pain. But the problem is: this person isn’t actually working on being a writer but, instead, has focused on becoming a writer. Which is to say, they’re far more invested in a public persona that screams WRITAH and less in actually writing. And somewhere along the way they’ve forgotten how to write.

This person is also someone who’s used to getting a lot of empty-calorie adulation on Twitter for vicious Takedowns. Reading their work, the writing they think represents all their Creative Genius, I realise how badly formed it is outside of the bright Umbrella of Validation they’ve created on Twitter. I’ve never thought much of their tweets but it was always mildly amusing to see what they had to say. On Twitter, these writers (or people who imagine themselves as such) are able to forge Personalities, as people who speak in strong and often cruel and snarky, short sentences. Twitter is a closed loop of call-and-response: someone says something, others pop up to clap their hands (by retweeting, responding, or some combination of both), the account in question is emboldened by the adulation and continues onwards, twisting the knife ever deeper until they emerge with, say, someone’s beating heart or lungs and having torn and shredded their reputation to shreds. At which point, there is much joy in the streets of Twitter, the blood runs strong and red, and then after a while — sometimes inexplicably as far as the Writer is concerned — attention drifts elsewhere.

Twitter crowds are notoriously fickle, and they have the collective intelligence of Sea Squirts — which is to say, none at all (the creatures are famous for effectively absorbing their own brains). One of the least discussed aspects of Twitter is that nearly all the most tumultuous “events” which happen on the site are created by a tiny, tiny fraction of mostly fake accounts. In her latest book The Palace Papers, Tina Brown points to the research of a group called Hope Not Hate on the Twitter feed of Meghan Markle, who saw a massive amount of pushback online: “70 percent of the five thousand snarling messages posted between January and February 2019 were revealed to have originated from the same twenty hostile accounts” (the report is discussed in this Elle article). I haven’t combed through HNH’s research to see whether its claim holds up but nothing about this finding surprises me. I’ve long held that a vast majority of Twitter accounts — by my estimate, easily up to 90 percent, yes, 90 percent — are fake, in that they’re either bots or simply multiple accounts created by a relative few. The problem with Twitter is that every “controversy” isn’t just loud, it’s also often deeply vicious and the ability of fake or real accounts to deftly pile on and create turmoil has meant a chilling effect on, for instance, publishing and larger cultural discourses on, well, just about any subject you can name.

But there are those, like the aforementioned writer, who think they can outsmart the system, that they can somehow own it, and they keep returning. Are people bored with the original set of tweets about a fellow writer? Give the masses what they want in the form of a takedown of a local diner! Whoops, does that particular genre now fall flat in a pandemic where precarious indie businesses (even with all their adorable labour-unfriendly practices) cannot be criticised? Scratch that, let’s post a stream of thirst trap photos. Interspersed with a rambling set of “thoughts” about the latest Marvel film. When that doesn’t work, whip out some pics of your dog or, hell, borrow your neighbour’s cat even at risk of having your eyes scratched out because, hey, an angry scar brings views, and when that doesn’t work, tell everyone that you’re depressed or that your best friend has a medical emergency and so on and on and on and on. Yell at the president (and secretly wish Trump was back because you could say the meanest shit and people would cheer you on). Yell at many Someones. In your lowest pit of desperation, you might even write to another writer who has been critical about something — it doesn’t matter what, exactly — and try to get them to fight with you in public. When they simply block you, thus cutting you off at the pass, turn your rage upon them and scavenge off the hits you get from the trolls circling around you, looking for fresh blood to drink. Complain that you are discriminated against because of your weight. Mock someone else for not being attractive. Talk about your bowel movements, often, pimp out your cute cousin’s photos and enjoy half a day’s worth of tweets where you pretend to be sweetly fighting off her would-be suitors online — until your cousin finds out and tells you “fucking cease and desist, or else.” Post even that message on Twitter — because you don’t care about her feelings of being violated — giggle, and go back to writing about how you can’t write and how bad the systems are, and how the trauma you suffered at 18 was the trauma of being online, and so on.

These examples form a satirical composite portrait — there are a lot of writers online who sustain their public selves in oddly similar ways. But I do want to return now to the example of the one particular person I began by referencing. As I said, I’ve been following them for a while and had high hopes for their work. At some point, they were finally able to devote time to their writing — a dream for a lot of us. As I scrolled through the posts on their platform, I expected to find at least a few hidden treasures, some sparkling, beautifully polished gems of writing that were the result of hours of honing their — dare I say — craft.

Instead, what I found was a vast, flat wasteland of work, some short and some long pieces that just sort of … sat there. I could see every now and then the bits and pieces they had imported from Twitter but the exercise never worked. You can say something very smart and funny in 280 characters and it will carom with lightning speed towards the ends of the known Twitterverse and back, perhaps picking up as many as 6 new followers on its return (or 600 — Twitter is unpredictable like that) but the mysterious quality that turns a set of words into a “viral” sensation has nothing at all to do with how words and phrases and sentences work in actual writing-writing. The themes were fine — a brilliant editor friend points out that you can actually literally write about anything and make it a fantastic piece: the point is not the topic, but the execution. But here, from someone who had once been a decent writer with potential and who now spent most of their days hurling bluebird-shaped lighting bolts into the Ether of Nothingness, was a whole lot of, well, nothing. The tone and shape of the work was just grey, and that’s the best way I can describe it. Not always gloomy, just colourless, even in the pieces that tried to be jaunty and, you know, fun. There was an inevitability about it all and everywhere, littered like the detritus of an unhappy picnic on a soggy day, were the “quirky” bits that had worked as tweets but now served very little purpose.

It became obvious to me that months and months of being A Very Prominent Twitter Account With Several Viral Tweets had sapped any actual talent that existed in this writer and resulted in lifeless writing that simply could not stand on its own. Attempts at humour or pathos or anything else were written towards a presumed audience of 330 million (by Twitter’s official and absolutely bullshit count) but the thing is: writing is an act of intimacy. When you write, you’re imagining a crowd of readers, sure, but it’s a many-headed audience of one, a Hydra if you will, quietly bobbing its many faces back and forth, gently ruminating on the quality of your prose before it decides to yank your head off. You’re not writing for a multiplicity of sensibilities, just many different bodies with a similar focus and set of interests. And yet, at the end of the day, you’re also writing for yourself — that’s really what many of us writers mean when we say that writing is a lonely act. It’s not lonely in the sense of some sense of alienation (though that can be a very good thing in many kinds of writing, and more writers need to feel that, but that’s a separate topic for another day). It’s lonely in the best way and in the sense that, at the end of the day, it’s you and those words out in the void together. The question for you as a writer should not be, Will hundreds of people like this? It should be, Do I like this? Is this the best version of this I can produce?

This particular writer has become used to an audience, and has no idea how to discern whether or not a paragraph, a page, a sentence, or a word might work without the response of mostly nameless strangers. Reading their work was like watching a comedian only used to the constant, clamorous applause of a live studio now suddenly thrust in front of a standup audience at the famed Apollo (the toughest audience on the planet, according to many): Where are the cue cards? Someone tell them they have to laugh! Bereft of their Twitter hordes delivering them their Dopamine fix of constant likes, this writer has forgotten how to — again, dare I use this word — craft their work. Does this work? Is it funny? Should I be funny or sad? Wait, is there anything else?

This is a problem that plagues many, and it has expanded into publishing with too many mainstream editors and publishers pushing writers to produce pieces that will bring eyeballs to their sites, no matter what. I know one writer who became famous for their “searing” takedowns of writers and directors, and they have written for some of the top ranked outlets. The problem is that after a while all their essays seem exactly the same, with almost exactly the same points, and the readers — at first delighted — soon tire of it all. So they move on to another publication, and continue on down the line. I mean, hey, whatever, it’s a living — a damned hard thing to make as a writer who’s not independently wealthy. The problem arises when writers adopt a style meant for virality and little else and it becomes second nature to the point where they actually forget how to write for real people (and those do exist, and they — not your followers — are the ones who actually buy your books). I know a writer — a somewhat successful one, actually — who creates and writes about their Twitter fights where there are none. I can always tell when they are freaking out that no one is reading their work because they whip out another incendiary post about how everyone misreads them and, damn it, they’re going to set things straight….a friend calls it shadow-boxing, a brilliant term for what goes on a lot in the World Of Writers On Twitter. If a tweet falls flat on Twitter, does it even make a sound?

And this, Dear Grasshoppers, is the warning I have for you: If you can, become one of those Unicorns among writers, the sort who don’t have to be on Twitter to endlessly promote their work (and take me with you). Failing that, use Twitter in a way that works for you: in short bursts, perhaps, or only on some days, or with the nifty scheduling tool. Twitter can actually be a good place to be, but you have to work at finding your audience and your crowd. Being a writer is about writing, not about creating a personality. Never mistake your life on Twitter as anything akin to your writing life.

*******

Update: the title of this essay has been changed from “On Writing, Part 1, ‘Twitter Is Not Your Writing Life.'”

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

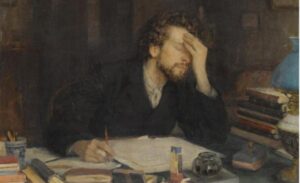

Image: The Passion of Creation, by Leonid Pasternak, 19th century