I shouldn’t have to endure quite that degree of preciousness over a morning cup, but this is coffee country: my thoughts are heresy, and they flay people for less.

There’s a new Philz Coffee in Hyde Park, another outpost of the famed San Francisco chain. Experts will tell you that it’s part of the third wave of coffee culture: the first includes mass market coffee (think Folgers, or that jar of Nescafé discreetly lurking on my kitchen shelf), the second is represented by Peet’s and Starbucks, which forcefully and ubiquitously displayed what we might call their chainicity but also introduced espresso drinks on a mass scale and encouraged us to think about matters like sourcing and roasting. The third wave is what we’re riding today: coffee procured and made so artisanally that you can talk to the farmer who grew the coffee that goes into your morning pour over as you caress each individual bean before pulverising it into a grind of your choosing.

Where Starbucks promised consumers a corporate branded experience that would be the same everywhere, Philz consciously works to blend into the neighbourhoods where it sprouts its branches. It’s the Whole Foods of the coffee world: carefully curated to bring you the advantages of a chain (with its convenience and seeming abundance) with the feel of a local store: The HP location carries pastries by local baker Fabiana Carter but the rest of the menu is the same as found in every other location.

Philz doesn’t serve any espresso drinks and it takes pride in the fact that each cup is made to order. Its company philosophy seems like a manifestation of Google’s famous (and deeply hypocritical and utterly untrue) dictate: “Don’t be evil.” Run by Phil Jaber and his family, Philz appears to take pride in what they describe as a friendly and community-minded atmosphere; the goal is optimal happiness for everyone, staff (dare I call them that, when Jaber refers to the baristas as “artists?”) and customers alike. They guarantee hiring decisions within a fortnight, and offer feedback even to the rejected.

Philz’s third wave-ness is made manifestly clear as you enter and ushered towards your barista. What follows makes for an experience that’s as unique as Jaber and his family describe but also, and this will strike many as sheer blasphemy, deeply uncomfortable. Philz forces you into a realm of social interaction that strikes me as both needless and pointless. And also, to repeat myself, deeply uncomfortable.

Perhaps it’s a Midwestern thing—we like to effusively ask “How are you?” without really wanting or waiting to hear the answer. Those who naively assume we’re sincere and who unburden themselves to us are greeted with that slow, sideways walkaway and a slightly pained expression that says: Must you? I mean, I’m so sorry but I have a train to catch or a dog to walk, so bye now.

Philz, with its intense interactions between customer and barista is, what’s that word, yes, Californian to the core.

Which is how I explain, afterwards, when my mind finally begins to process it all, the experience of ordering a simple pour over at Philz. The first barista I encountered there, during one of the store’s soft openings, launched into a conversation—a conversation—about hats (I was wearing one of my favourites, a giant black and white affair). Not simple chit chat, the sort I’m used to at all my regular haunts, where the parameters are strictly laid out, artfully and almost, in a way, wordlessly, each person on either side of the counter understanding full well that ours is an interaction much like a random quickie alongside a broken toilet somewhere on the interstate, with no names taken and no details offered at the end: all enjoyment savoured only in the moment, with no post-coital chatter.

But here, at Philz, I am taken by surprise as the words rush at and from me pell-mell, and I feel once again like a child at a party, being prodded by a parental unit to “be polite and make conversation, and not be so rude.” And so the conversation takes on depth and detail, and I find myself towards the end feeling wanting, like I have to bring it all to a conclusion somehow, and I offer the information that there is an actual hat place in the Monadnock building, and that even if they’re expensive they certainly seem to be worth the money. In the middle of all this, I’ve been asked how I like my coffee and a part of my brain just wants me to reply, “Like coffee?” but once again, my hapless inner child is compelled to begin what seems like an eternal conversation and I ask for a pour over, which then begins a discussion of the coffees that might be best for that and dear god, I think, will this never end and please can I be done now. I choose, my mind still reeling, and retire to the waiting area (yes, there is actually a waiting area for coffee).

It doesn’t end there. Once I get my cup, I hope to make a speedy getaway. But the (really very sweet and kind) barista wants me to tell her how it is, because she wants to make sure I’m, what’s that word, yes, happy, and I sip quickly, something I ordinarily never do at the counter itself because who the hell does that and I’m acutely aware that there must be people behind me and do I really have to do this, like, now, tell you what I think? What happens if I don’t like it? but I glug a bit down and tell her it’s great, and I don’t think I was lying because, whatever, it must have been great or at least fine and I finally escape out the door to sweet freedom.

I felt helpless, like a child adopted from a wartorn country who has no choice but to mimic the cheery banter of its new family in a shiny and well-fed new world, admonished to be happy all the time: Now that you taste freedom, you should feel free to tell us if you like your toys or not.

Philz coffee is fine, not great: the founder claims to have discovered a process by which to remove the acid in coffee beans. Whatever they do denudes the beverage of a certain tendentious bite, an unpredictability and bitterness that helps to make a cup more interesting than the carefully planed down flavour (the word is “smooth”) that seems so popular in everything these days. Still, I like pour overs, so I return. By my second visit, I’ve steeled myself, or so I think, and decided I won’t take any more of the interactiveness of it all and will try hard to be politely but quickly enthused and convey little more than, Listen, could I just, please have my coffee and leave? That is, of course impossible. Another barista asks me how I’d like it, I choose my coffee, ask for it with a smidge of cream, and just as I think it’s all over, it starts again and there is talk of mint or something and a very exacting conversation about the level of sweetness (I want none). At Philz, they keep the cream and sweetener away from you, a move that seems to contradict the whole “Coffee as you like it” ethos. It feels more like an exclusive bar, I mean, an alcohol bar, not one that serves coffee and why does a cup of coffee have to be laden with so very much? If someone wants to be tyrannical with me about how they serve that rare whiskey found at the bottom of the ocean in the wreck of The Titanic, fine. I shouldn’t have to endure quite that degree of preciousness over a morning cup, but this is coffee country: my thoughts are heresy, and they flay people for less.

As with the last one, this barista, also very kind and sweet, wants me to let her know what it tastes like. This time, too exhausted to carry on any more, I barely mumble, turn away from her and walk towards the door. From the corner of my eye, I see her face fall, or at least I think I do, but I may be projecting because, well, because how can I not, given that the weight of the whole world has borne down upon our interaction over a simple pour over?

At Philz, I’m forced to perform a self that I don’t generally deploy in, of all places, a coffee shop. That’s not to be snooty but to say that the chatter at Philz feels exhausting: it’s laser-focused towards a judgement about a product right in front of the person who makes it for me. Why can’t I go back to the old days when I might, for instance, yelp about it afterwards, or even, who knows, just not care either way? I worry that someone, somewhere from corporate is watching her and will dock her pay because she failed to elicit any kind of response from me (company policy dictates that every customer must be acknowledged by an employee within 18 seconds, so who knows what other rules exist). I scurry outside, convinced I see her looking longingly at my back, dreams and hopes crushed for the day, or at least till the next customer steps up.

For more on Hyde Park restaurants, see also “Hyde Park: Where Food Goes to Die.”

Yasmin Nair lives in Hyde Park, drinks too much coffee, will probably return to Philz, and often writes satire.

The piece you just read is original to this site, and free to you. Such work can often take take months to produce, unfunded by any publication. If this made you think, changed your mind or even made you angry, please be sure to donate (even a small amount) or subscribe to support me. Please cite my work directly (not just in links) if it informs yours. Do NOT steal it. You can find out more about me here.

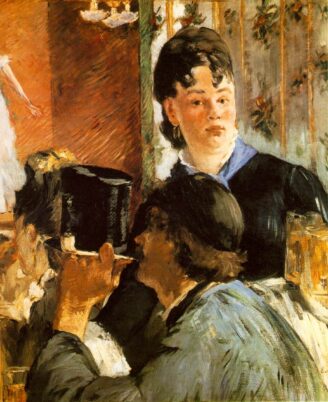

Image: The Waitress, by Édouard Manet, 1879