How different would our responses be if Toledo had been an adult facing the police and dropping the gun in exactly the same situation?

Adam Toledo was shot and killed by a policeman in the early morning of March 29 in Chicago’s Little Village neighbourhood. Today, released video footage indicates that he had dropped the gun in his hand seconds before he was killed. The city has been preparing for possible protests.

Toledo was 13, making him the “the youngest person fatally shot by Chicago police in years,” according to the Chicago Tribune.

The fact that he was a teen and therefore still a child has resonated in public discussion of this case and the figure of “the child” is now being deployed on all sides. Mayor Lori Lightfoot warned the public that the video was “excruciating,” and that “watching the body-cam footage, which shows young Adam after he’s shot, is extremely difficult,” adding, “And I would just say … as a mom, this is not something you want children to see.”

We might add that “young Adam” was also a child and that children should not be shot. But, of course, because he’s not a white child, commentators have already demonised him. Notable among them, Eric Zorn of the Chicago Tribune chimed in to say that it’s time to “stop romanticising and infantilising 13-year-olds.” Zorn helpfully gave us a list of no fewer than five instances of teens engaged in violence, helping us to grasp the absolutely epidemic nature of this problem. I haven’t dug deeper into the cases he references, but all my spidey-senses tell me the youth in question are probably not white.

Responses to Zorn were swift, at least on social media (apparently even Newsweek doesn’t employ enough writers to actually interview actual humans but can “report” that people are in fact tweeting about an issue). Zorn has since issued an apology of sorts.

The hypocrisy surrounding “children”’ in this case needs to be critiqued from all sides. But we can also end up focusing too much on this matter of whether or not Toledo was a child. At this moment, public figures who want to be seen as being on the right side of the debate are going out of their way to describe what I will call the “childness” of Toledo, describing him as a boy, a child who still played with Legos and Hot Wheels at home and should not have been killed.

How different would our responses be if Toledo had been an adult facing the police, dropping the gun in exactly the same situation? Minutes before his death, Toledo was spotted in an alley with 21-year-old Ruben Roman, who has since been arrested: NPR reports that this was “over what police described as a ‘probation violation warrant for his participation’ in the March 29 shooting, and he also faces three felony charges: reckless discharge of a firearm, unlawful use of a weapon by a felon and endangerment of a child.” If Roman had been chased and shot, would we be even half as outraged at what transpired?

The Toledo case has raised issues about how we demonise some families and parents and children because of their race and socioeconomic background. Criticisms of Toledo’s mother for supposedly not having been around to supervise him have been met sharply with critiques of a larger social structure that leaves families without resources that include childcare. All of that is important, but I hope that the focus on Adam Toledo’s status as a child eventually dies down because his childness is not the point. I hope we redirect it instead to the central problems with policing linked to the many issues that plague neighbourhoods like Little Village, whose residents face the constant threat of gentrification and displacement. The Toledo shooting comes at the time of the Derek Chauvin trial as we watch, once again, images of a white cop leaning hard on George Floyd’s neck, with his hand casually tucked into his pocket all the while. The problem is not that there is no such thing as a Black or brown child in the eyes of the police. The problem is that in the eyes of the police, there is no such thing as a Black or brown human.

Was Adam Toledo a child? Yes. Would he have been treated the same way if he’d been a white child? Probably not. But does focusing on his status as a child help us get any closer towards understanding the complex web of social, economic, and political circumstances that led to his death? The emphasis on his youth won’t help make more people more critical of policing. When we create exceptional victims, we aren’t calling for an end to the system that kills people. We’re instead implicitly pointing to other kinds of people and insinuating that they’re the ones it’s fine to kill: saying that one kind of victim did not deserve to die is stating that there are those who deserve to be shot and killed. Is that the world we want?

***

For more, see these other pieces.

“The Politics of Storytelling.”

“On Death and Exceptionalism.”

“Hate Crimes, Exceptionalism, and the State’s Order to Kill.”

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

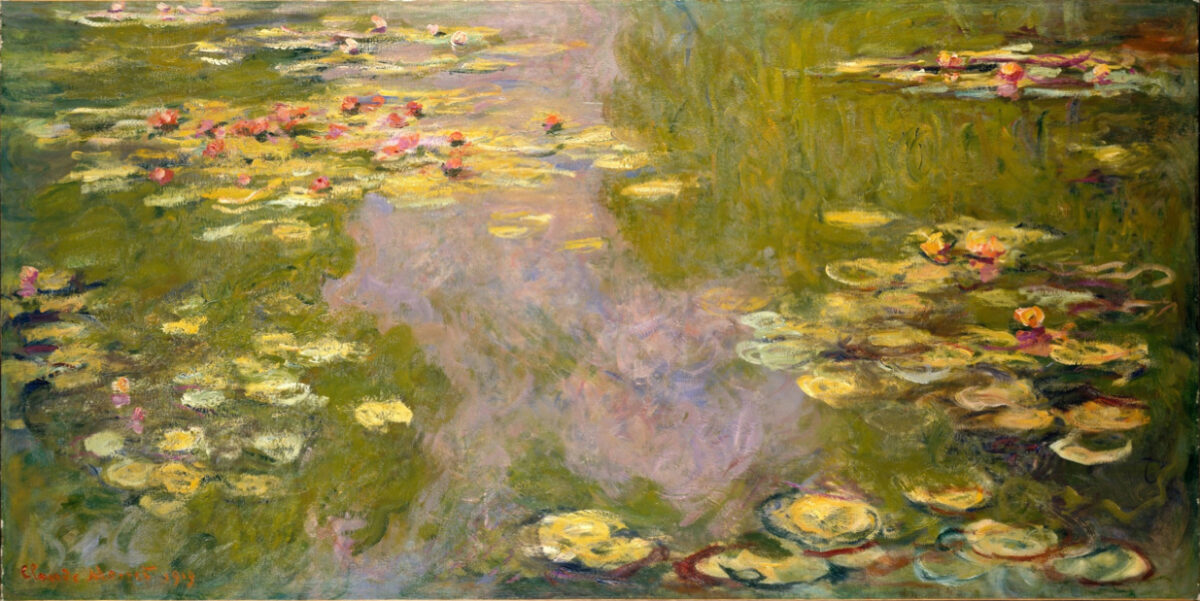

Image: Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1919.