This review of the movie Mr. Holmes contains at least one spoiler.

It is 1947. The venerable Sherlock Holmes (Ian McKellen) is 93, has left London for good, and lives in Sussex with his housekeeper Mrs. Munro (Laura Linney) and her young son (Milo Parker). Instead of the trademark deerstalker hat and tweed Inverness cape, he now wears a black top hat and a fitted black coat, his lanky figure still making a distinctive impression as he weaves his way through the world. There are now cars all around him, and the bombing of war has begun in many parts of the world. India will gain independence, the Raj will soon be over, and Hiroshima, the site of a week-long visit for reasons we only gather later on, has been bombed into an arid, parched landscape of withered trees. A woman walks by Holmes and his guide. She is perfectly attired in a kimono and has long dark hair but as she turns, he sees scars running down her face.

Holmes has been led to Hiroshima in search of yet another curative for his failing memory, extract of prickly ash. He has to scrawl the name of his host, Tamiki Umezaki (Hiroyuki Sanada) onto his cuff so that he remembers how to address him. Back home, he becomes even more frail and his doctor (Roger Allam) asks him to make a mark in a diary every time he forgets something like a name. In weeks, the book is filled with inky disclosures of how much the storied mind, once the scourge of criminals everywhere and seemingly incapable of ever letting go of any vital piece of information it came by, is beginning to lose.

Mr. Holmes comes painfully close to the maudlin — how can it not, we might ask, with the presence of a child in the same house as a famously acerbic and reclusive genius? This is so often the basis for trite narratives about grumpy old men softened by the presence of winsome children. But it’s to the credit of this deeply engrossing film that the relationship between Holmes and Roger is of mutual respect and admiration. The boy is sharp and acidic in his own way even, at times, at the cost of great cruelty to his mother whose grammar he begins to mock the more time he spends with Holmes (the class narrative here is understated but beautifully narrated, without being didactic). He knows about Holmes’s reputation and, sleuth-like, snoops in his study to find out more. There is, he discovers, a last mystery left unsolved. Holmes is reluctant to talk about it, and the film follows his slow, reluctant disclosure. Meanwhile, there are bees to be tended to, bees that provide Royal Jelly, also reputed to help with memory and possible senility.

But the bees are being killed. Every day, Holmes and Roger find their tiny corpses littered around the apiary, and they don’t understand why. Also a mystery is Holmes’s relationship to the striking and melancholy woman whose photograph he still possesses. Her story, that last one, slowly unfolds: her husband Thomas Kelmot (Patrick Kennedy) came to Holmes for help years ago. Ann Kelmot (Hattie Morahan) still mourned her two miscarriages, a son and a daughter, and she wanted to buy headstones for them as if they had been birthed. In an attempt to distract her from her sorrow, he bought her music lessons for a water harmonica but ended them after she became obsessive about playing and he heard her talking to her unborn children. Soon, her behaviour became even more erratic; Holmes is hired to find out more.

In Mr. Holmes, we are prompted to ask: What happens to old people who are alone? To be specific, what happens to people whose solitude comes about because the gifts they have or the wounds they bear make it difficult for them to inhabit the world as others might?

In a key scene, Holmes and Ann Kelmot sit in a beautiful garden as he reveals to her what he has deduced: that she knew he was on her trail and deliberately worked at convincing him that she was about to kill her husband with poison when, in fact, she planned on killing herself. In an inexplicable moment, she turns and asks if he might join her in her solitude. He counsels her to return to the husband who loves her and as she walks away, he is, perhaps somewhat smugly, assured of having both solved and satisfactorily resolved a case. But she in fact only leaves to throw herself in front of a train.

What do we do with aging genius? How do we explain genius outside of the heady, glamorous contexts of youth and excitement? In Sherlock, the updated BBC series starring Benedict Cumberbatch, we have reached a first-name familiarity with the famous detective and all the death and mayhem is set in a sexy London and the even sexier mind of its lead character. It’s altogether a different representation from the earlier 1980s series starring Jeremy Brett, who was literally dying on screen in the last episodes: gravely ill then, he finally succumbed to a heart attack in 1995, but his ashen and puffy face testified to his state of health before the end. Brett was as brilliant as Cumberbatch is, in an entirely different way: his Holmes was suffused with the deep melancholia of a man who knows too much about the world and its inhabitants.

That knowledge seems to be the unbearable burden of great detectives, and it explains the depression that suffuses the lives of so many of them. In Mr. Holmes, we have a film that needs to explain why he would be so melancholy. It could have turned into an abstract and a more interesting set of ruminations and simply explained that the world is in fact a dreadful place. That horrible people do horrible things to each other, that bombs and radiation effects spanning generations are the “collateral damage” we inflict upon entire countries, that sometimes the sadness people wander into is so unbearable that we need to let them inhabit it completely, or watch them slip away.

Instead, Mr. Holmes gives us comfort in the shape of a possibility of joy, of un-solitude. If Holmes had take up Ann Kelmot’s offer, would his life have been so different? More critically, we might ask but are not allowed to, is a life steeped in solitude only one to be mourned? Was it, is it not enough that the world’s foremost detective should be allowed to retire with his bees and muse fondly upon a life well-lived?

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

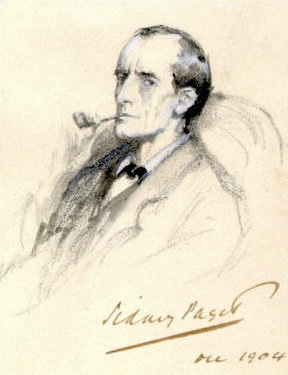

Image: Sidney Paget, 1904.