If you like this, please consider supporting my work.

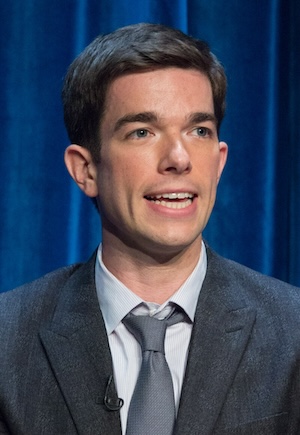

When John Mulaney’s Everybody’s in L.A. appeared on Netflix last May, it was as if humankind had reinvented fire.

This is not an insult: there’s fire, sure, and we all get used to it. For aeons we trudged along and thought of it as both the potential for great tragedy, and as something fundamental to life itself. Don’t sleep with a cigarette in your hand. Do set those coals on fire so you can have that burger.

Such was the predictability of the late night television show, graced for so long by the likes of Johnny Carson, David Letterman and, more recently by Seth Myers and Trevor Noah. The last of that lot has since entered the world of streaming, joining comics like Conan O’Brien who combine podcasting with specials on Max, possibly for more money and flexibility than what was allowed by conventional television programming. There was a time when an appearance on the Johnny Carson Tonight Show could make or break an actor or a comic, when a mere nod of approval from the man himself signaled to millions that a performer was worth their time.

The rise of streaming services has changed all that. With a seemingly infinite number of choices, consumers are less likely to wait up for a conventional late night show. Last year, the Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon was trimmed to appear only four nights a week, and Late Night with Seth Meyers lost its house band to budget cuts.

And then along came John Mulaney, who teamed up with Netflix to create a limited version of the classic late night show to coincide with the Netflix Is a Joke Festival, titled, aptly, Everybody’s in L.A (since everybody was). For six nights, Mulaney strode out onto a stage, announced the time and temperature, and then began an experiment that was at once as wondrously new and exciting as the first flames of a fire millennia ago, and yet somehow as recognisable as the roast chicken you picked up on your way back home.

Everybody’s in L.A is hard to describe because it is something only Mulaney could have conceived and executed, defying all genre expectations. Are there guests? Yes, and they all sit near the host on a sofa and chairs, much like the people who are invited onto the Meyers show. But where the conventional show set is relatively bland, so as to not detract from the host and guests, this one is designed to look like the home of someone who moved into a house somewhere on Mulholland Drive in 1970, and who has stubbornly refused to change the decor for decades. There is, behind the sofa, one of those indeterminately artistic wooden sculptures, which some of us remember from our childhood, probably named “Spirit” or “Woman Flying”—expensive at the time and soon to be found in a thrift store for $10.99. There are bowls of glass fruit, which are not pretty—and no part of them looks like fruit. There is a sidekick, Richard Kind, who is sweet, goofy, and also on occasion menacing—which is to say, perfect as Richard Kind playing Richard Kind. There is Saymo, an adorable delivery robot with large eyes and an eagerness to serve that breaks one’s anthropomorphising heart. The first episode features Jerry Seinfeld, who takes one look around and declares, “This is the weirdest show I have ever been on in my life.” And “weird” barely scratches the surface.

This is fire, reinvented. It is live, but in a way that is electric, the way that conventional shows of its ilk have forgotten how to be. Each episode has a theme, and a set of guests both well-known and unknown to the general public. Episode 5 focuses on earthquakes, and introduces the seismologist Dr. Lucy Jones, who discusses the different kinds of quakes and their dangers with David Letterman and Mulaney. There are cutaway taped sequences, including one where Mulaney and a crew of comics try to buy a house in L.A.—the running gag is that they keep breaking things.

Everybody’s in L.A makes live television come to life again, even though it is not, strictly speaking, on television and has now been archived in its not-live version, to reside in that monumental and somewhat cluttered Netflix bank until the streamer decides it’s no longer worth keeping around. There are, on YouTube, a million excerpts from any number of shows featuring Letterman, Carson, Kimmel or Meyers: as with Saturday Night Live, viewers often watch conventional shows in bits and pieces on the morning after, tipped off on the must-sees by mentions in their social media feeds. But I have watched nearly all episodes of Everybody’s in L.A multiple times, in their entirety, finding something new to laugh at or revel in every time. There is a quality of nothingness to it—something that Seinfeld pioneered—a shambling, exploratory drive, an unwillingness to be bound by convention that somehow manages to keep you watching.

Everybody’s in L.A was a gamble, but became a hit, or whatever term streamers use to call Something That Lots of People Watched and Made Executives Happy. So, of course, Netflix, which likes to suck the marrow out of the bones of every living thing, gave Mulaney the chance at a second season (or whatever it is that streamers like to call Something That Is Allowed to Return). It is now called Everyone’s Live with John Mulaney because, apparently, focus groups have no great fondness for the city in which it is based. It will run for twelve episodes, and has dropped three so far.

This time, though, the fire, while still there, seems to be dwindling into embers.

The set is mostly the same, but there are more bowls of glass fruit—four, as opposed to the two on the previous season, and much bigger—on a much larger coffee table. This does not bode well. On conventional sitcoms, the arrival of a baby is always a sign that the writers have run out of ideas. No plot for this week? The baby’s sick or, better still, wrap a whole episode around how the father can’t find the bottle! Something! Are the bowls akin to babies, distracting us from the fact that the show seems to be lagging?

Mulaney, like O’Brien and Seinfeld, is in that pantheon of comics we can and should refer to as comedic geniuses. What connects these men (besides their race and gender, and that we shall discuss another day) is the seeming effortlessness of their work. All great art looks like it took no time at all, and the surge in comedy specials—along with the larger amounts of money to be made from them—has had the effect of making standup seem like no work at all. The result is that everyone online seems to be trying out a bit, all the time, convinced that standup requires little more than the ability to tell a joke when, in fact, it demands a sense of narrative, timing, and the ability to pack entire histories into a few seconds without explaining everything to an audience. A recent Saturday Night Live episode, “Pop’s Big Regret,” spoofed the widespread delusion that comedy is easy. It revolved around an elderly mob boss who is mowed down by a rival gang. As his aghast and anguished sons cry over his dying body, the man reveals that he had always wanted to be a standup, and then proceeds to try out a few (very bad) jokes with his dying breaths. There was a time when you couldn’t get on the el without having to endure someone belting out songs in that made-for-TV, trilly, show-off-y way because everyone wanted to be the next American Idol. Today, everyone’s angling for a Netflix Comedy Special (and, apparently, judging from the vomitously large number of shows on there, everyone is getting a Netflix Comedy Special).

I was reminded of “Pop” as I watched recent episodes of Everybody’s Live (season two). It has bits of sparkle from the first season, especially in Mulaney’s introductions and the musical segments. But a lot also falls flat, like the Joan Baez and Michael Keaton appearances. The latter seems befuddled about being there, while the former launches into a classic Baezian (predictably bland and liberal) denunciation of the current administration and an anecdote about crashing her Tesla. There is much dutiful clapping.

All of this could still make for an interesting show—after all, failure is the premise of an unscripted event, and both tension and joy can be derived from watching the unpredictable moving bits and pieces to see where they might land. But Everybody’s Live suffers from the success of Everybody’s in L.A, and this is nowhere more apparent than in the call-in segments that were the glue that held the previous show together.

In both seasons, Mulaney takes calls from people who have been vetted by an offscreen team. In the first season, these were often the highlights and provided moments of genuine laughter, even when some were clearly scripted, like James Austin Johnson calling in as Bob Dylan. Some were surprising, as in episode 6, when L.A Mayor Karen Bass called in, and was asked about the ubiquitous palm trees and city planning for the Olympics. Other calls were hilarious and terrifying, like a woman’s anecdote about finding a coyote in her bedroom (it had sneaked in and climbed up the stairs, apparently in search of her cat). But there was an excitement to them because they were largely unscripted and genuine. In Everybody’s Live, the second season, the calls have been less spontaneous and people seem to literally be auditioning to do standup. On episode 1, a cruise ship chef launched into an anecdote that meandered so often that Mulaney had to ask him to provide “less colour, more story,” before finally shutting him down with, “You’ve told this story a lot, it’s become a yarn, and we don’t have time for yarns.” On the most recent episode, about funerals, a woman called in to talk about how she had packed her husband’s ashes into bullets that were then fired off at his funeral (as per his request). It’s a confusing story for reasons I’m not willing to untangle because that would require me to rewatch the rambling segment. It becomes clear that she doesn’t have much of a story beyond the packing of the bullets, but wants to talk about the deaths in her family. Mulaney doesn’t cut her off because, really, who wants to be seen as the jerk who shut down a widow who also lost her father recently? In yet another call, an Australian funeral celebrant wants to describe how his work collided with his work as a comedian, and it sounds like the beginning of a bit (Mulaney cuts it off before it becomes a performance).

Netflix routinely cancels excellent shows mid-stride—I am among the millions who will never forgive it for abruptly ending Santa Clarita Diet. Mulaney owes the corporation nothing beyond a show that will come to an end in a few weeks. So, really, it’s fine that parts of Everybody’s Live don’t work—that is the point of a fundamentally pointless show that correctly luxuriates in its pointlessness (again, not an insult). There are the odd and unexpected bits, like the cast of eleven Willy Lomans, played by actors like Christopher Lloyd and Anthony LaPaglia, who deliver the “there were promises made” speech simultaneously. It was, well, yes, weird: it worked and did not work, all at the same time. To watch eleven people deliver those words made them seem both less and more significant: memories of high school performances colliding with the iconic nature of a text. Did it work, or not? Maybe, maybe not, but it is hard to forget. Wherever the show goes, it will probably land in similarly bizarre places—and it will still be more interesting than the predictable late night shows which operate more like press junkets for movies.

The calls, though, should go: everyone’s phoning in their standup aspirations, and no one is as funny as they think.

If you like this, please consider supporting my work.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.