For Joe Palmer, who made sure I survived.

I published “On Plagiarism” in February of this year. It’s a long essay on the complexities of plagiarism and it had been in the works since at least 2011: I’ve been thinking and occasionally writing on the topic for a while, and I’d long promised my readers that I would definitely be publishing the long work on the subject, any day now. When the Claudine Gay scandal exploded at the end of last year, I thought I’d write something short, move on and back to the book projects that currently consume me, and then return to plagiarism in the spring. But, of course, that was not to be. I realised that the Harvard-Gay issue, with its complications around race, gender, and so much more, provided a way to write at length about plagiarism in both the academic and mainstream publishing world.

I’m back to working on the books and, in the meantime, have been watching news about plagiarism in academia unfold everywhere. And Harvard, it seems, is always in the news.

Some of that is because of a bloc of extreme right-wingers taking on what they decry as the “woke agenda” of Harvard. I find them and their claims of “radical” and “leftist” academics taking over the university—and, by extension, all universities—extremely amusing because, as anyone in academia can tell you (and some will cite many German and French philosophers on the subject), the university has historically been a place that incubates, nurtures, and encourages nothing but the worst kinds of conservatism and conformism. The university has always been where young people are sent to develop their sense of class belonging: the elites to places that teach them to quote Wordsworth and speak Latin, and the middle classes to the equivalent of trade schools for a little Latin, perhaps, but more to learn “skilled” work. Consider the emphasis on STEM and the ways in which cities like Chicago create public schools that funnel black and brown students towards the trades, and you see that Ye Olde Medieval instincts to separate the lords from the plebes have survived intact. (This is not to approve of the distinction that many snobs draw, between what they see as the ennobling liberal arts and supposedly coarser trades, but to point to them: I have little patience for liberal arts professors who defend their funding by crying out that they are not schools for mechanics, damn it.)

The scholars most targeted by the likes of Christopher Rufo are often in the humanities because, according to him, they have brought evils like Postmodernism and Theories of Sexuality upon the innocents who wander into the sacred halls of Harvard in search of a pure, Western education (where, of course, there has never been any questioning of the concept of “truth” or sex).1Readers will note that I don’t mention Queer Theory, and that’s because I consider this to be a remarkably conservative and even neoliberal field of study. I write about this here.

All of this is hilarious: liberal arts departments are composed of some of the most culturally conservative academics you could ever meet because the liberal arts are culturally conservative. There is nothing inherently radical or even leftist about the study or the teaching of arts and poetry and fiction. Can the arts and poetry and fiction be radical in themselves? Yes, of course (tear my worn copies of Dickens and Austen from my cold, dead hands). But when corralled and managed as fields of study, they have historically, fundamentally been about ensuring that bourgeois ideas about taste and morality and the family are maintained and disseminated. There are some who imagine themselves as leftists on Twitter who coo about legendary “cool Marxist” professors but the fact is: those were nearly all white men married to long-suffering wives who did all the laundry and cooking while working at jobs that saw their spouses through college and raising their children. The “cool Marxist professor” was nearly always a sexist jerk who, more than likely, also fiercely resisted the unionisation of graduate students when his dean asked him, quietly, gently, over a very nice meal at a very nice Italian restaurant, if he really wanted a salary freeze. He needs to be literally and figuratively retired, permanently. (To be clear: I have in fact been taught by genuinely cool Marxist profs, but they are not the sort valorised as such because they didn’t act like “cool Marxist profs,” and sometimes they didn’t even teach Marx in the most obvious ways.)

But we digress.

All of this is to say that if we are to think long and hard about the “state of the university” and especially the humanities, we have to find a way to counter right-wing attacks on places like Harvard and its supposedly radical, cutting-edge faculty without replicating ridiculously outdated and infantile ideas about knowledge production itself. That starts by asking very long and hard questions about power and plagiarism.

Harvard seems to have a particular problem with plagiarism although, again, to be clear, it’s one that’s persistent across academia and the institution is certainly being singled out. Still, we (that nebulous, mysterious “we”) may well expect Harvard—you know, Harvard—to do better. But should we? After Gay, Harvard’s Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer Sherri A. Charleston faced accusations of forty counts of plagiarism. Most recently, Francesco Gino, who was placed on unpaid administrative leave in June 2023 after initial accusations, is under fire yet again: a recent Science magazine article claims there is even more evidence of plagiarism from sources as varied as blog posts, students’ work, and other academic publications.

(Gino is a behavioural scientist who specialises in honesty. I’ll just leave that there and move on.)

Perhaps it’s time to ask: is Harvard the problem?

By this I don’t mean to imply that Harvard is some kind of sacred standard-bearer for ethics and scholarly standards. Plenty of educational institutions around the world produce excellent research in various fields, and their work is not influenced by what goes on at this particular institution.

But. The fact is that Harvard is more likely than most to get funding and institutional support for the kinds of projects headed up by researchers like Gino, certainly more than much smaller institutions. Harvard paid her a million dollar salary and Fortune reports that “companies paid tens of thousands more to book her for their private events.” There’s real money involved in all this, and with that kind of money comes the power to include or exclude people from work that could, if noted on CVs, mean all the difference between a middling career and a high-flying one. That money and power in turn foster a culture of fear and bullying. A New Yorker article describes the experience of Zoé Ziani, a graduate student who tried to express her doubts about the validity of Gino’s research findings (the problem was not simply plagiarism but that the data appeared falsified):

Members of Ziani’s dissertation committee couldn’t understand why this nobody of a student was being so truculent. In the end, two of them refused to sign off on her degree if she did not remove criticisms of Gino’s paper from her dissertation. One warned Ziani not to second-guess a professor of Gino’s stature in this way. In an e-mail, the adviser wrote, “Academic research is like a conversation at a cocktail party. You are storming in, shouting ‘You suck!’ ”

As the New Yorker puts it, Ziani eventually left the cocktail party (she got her PhD and currently works as a consultant). The Gino case is still bound up in lawsuits, but there are long-term and unseen effects, particularly for younger researchers associated with the project whose own credibility might be tainted (as the New Yorker points out).

And yet, the much bigger question is: is all of this likely to end the ways in which plagiarism functions not as a symptom of a few bad apples but as something that’s integral to the system? When Ziani and others raised their issues, they were effectively threatened with ouster from not just an institution but an entire field. The cocktail party comment was the equivalent of “You’ll never eat lunch in this town again.” What happens to those who stay on at the gathering, either too scared to leave or willing to endure what they think are temporary humiliations and the theft of their work (or that of others)?

Those people get jobs in other institutions (or at Harvard itself) and then replicate that behaviour and those attitudes. Plagiarism isn’t just about stealing work: it’s an indication of a willingness to exploit and demean the labour of others. You don’t have to be a cool Marxist prof to see why this is a problem, or to refuse to engage in this behaviour. And when you resist, you are taking on a gigantic institution with massive resources (Harvard has a $50 billion endowment). Those who deliberately stood in Ziani’s way and bullied her were happy to go along with their masters’ bidding and, let us be clear on this, were acting as representatives of Harvard.

It may not be the case that anyone in the upper administration of Harvard wrote directly to any of the professors to influence their response to Ziani, but it’s clear that a significant number of people across various levels knew of her suspicions that something was awry—and pressure was exerted on her. Power doesn’t always work in the clunky ways we imagine or see happening in the movies, with secret meetings or cabals to direct the course of events and to determine who gets silenced. Rather, institutional traditions—like knowing, instinctively, who must be disposed of and who supported for keeping the status quo alive—exist as internalised knowledge in the DNA of universities, not as memos (for that reason, the email sent to Ziani is actually surprising in how intemperate it was). The professors went ahead and decided to bully the graduate student instead of jeopardising a million-dollar plus enterprise (Gino’s success drew more funders and acclaim for the university). They, the administrators and the students and researchers who stood by and watched, will replicate that kind of behaviour everywhere they go. Other institutions and individuals will look on and adopt similar ways of operating, thinking, “Well, if it works for Harvard…” And on and on and on.

We can look at the example of Gino as some wild aberration, which is clearly how Harvard would like to spin it. Certainly, such cases of rank plagiarism, manipulation of research data, and mistreatment of those who dare speak out is not exclusive to the institution but we can argue, just by looking at the outsize influence of Harvard in so many fields and its ability to claim to be the “best” at everything, that its methods of operation are emulated by too many others.

The time may well come when a Harvard degree is looked upon with more suspicion than regard, but for now the university is still poised high up on its perch. I don’t wish to replicate that often annoying envy-fueled discourse about the place, and it has produced great work and scholars. The point ought not to be that we should save Harvard, but to make Harvards everywhere by taking and spreadings its considerable endowment among any number of universities and colleges. If money and resources were more equitably distributed among all educational institutions, greedy and unscrupulous researchers wouldn’t be given the opportunity to steal the work of the powerless. The latest incidents prove that plagiarism is not just about copying and lifting other people’s work but indicative of a greater rot. To be Marxist about it: plagiarism is not simply about the theft of ideas (which is serious enough) or bad individuals, but about the powerful exploiting the less powerful who cannot fight back and whose labour makes possible the profits enjoyed by those of a higher class status.

And to those who fight the fight: you are right to leave the cocktail party. Make sure you grab the cheese, crackers, and several bottles of wine on the way out.

See also:

“On Plagiarism.”

“The Dangerous Academic Is an Extinct Species.“

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

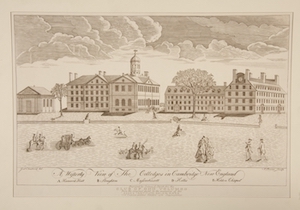

Image: “A Westerly View of the Colledges in Cambridge New England”, line engraving (after Joseph Chadwick), by the American engraver and silversmith Paul Revere. 12 3/16 in. x 16 15/16 in. Wiki.