When I was a wee undergraduate, I was in a tutorial with one of my favourite and most admired professors (today a bona fide music star, a long story). Tutorials are where you get direct supervision with a small group of fellow students, and you do a lot of writing and receive very detailed feedback. One of my essays was about the resistance I encountered in various parts of life and writing, and my prof gave me the best advice I’ve ever received. I’m summarising it badly (the original, with his hand-written response, is carefully tucked away in storage), but the essence was: “Don’t define your life or work simply by the resistance you encounter, because the resistance is not how you should be defining the worth and quality of your work.” He was and is brilliant and put it much better, but you see what he meant.

In recent years, I’ve taken to talking about the integrity of work, the necessity of following the course of a structure of thought, on its own terms. Another way of putting that is simply: Don’t write for your friends or your Facebook feed or retweets. I think there’s a lot of that happening, especially among writers who think they need attention (and, in a way, of course they do) and go about churning out work that becomes popular in a set of people they like or want to be liked by, as opposed to maintaining its own integrity.

As some or many of you know, I was the target of a series of vicious online attacks for daring to write “The Dangerous Academic Is an Extinct Species,” in Current Affairs. These attacks included raced and gendered vituperations of the worst sort, even when they came — perhaps especially when they came — from women and people of colour. As some or many of you know, you were part of that online mob, which is why, if you’re reading this on social media not as, for instance, a Facebook friend but from afar, you’re able to do so only because all my posts are public.

I’ve said that I will write about what happened, and I will but I have to work on processing all of it so that the piece I write is not about what was done to me, as horrific as it was, but what that violence and anger represented in the larger scheme of things, especially in terms of the crisis in academia. In the process, I’m doing what I learnt from my professor so many years ago, to walk away from the “me-ness” of a situation and think, and think, and think really hard about the anxieties and insecurities that rose so quickly to the fore. I need my piece to be about that, not about my anxieties and insecurities. (UPDATE: that piece, “A World of Shame: Time, Belonging, and Social Media) is now finished and can be read here)

Another way I see “resistance” defining work is in the current spate of right-wing groups going about and finding things to fault with supposedly left-wing professors and writers. And what I see happening here is similar to what sparked the Ciccariello-Maher incident: an illusion of alterity created entirely by the fact that some rabid right-wingers who can’t distinguish between, say, an ironic representation and, say, reality are angry. And my point isn’t just that it’s ridiculous to pretend that these are the great intellectual and political battles of our time but that there is a slow and steady attrition in the quality of what we might call “left” work and politics. If our definition of what is worth thinking about and acting upon is defined so much by what the Right hates — and it hates so very, very much — we’re already sunk.

This also explains why left output — in organising and writing and so much else — is so pale, tawdry, and often meaningless. If right wing campus groups are picking on gender and studies and race classes to criticise them, sure, we should be concerned. But opposition to our work alone isn’t what makes us “dangerous” or “radical.” The fact that the Right hates us, or the few of us who have the privilege of teaching in universities, in an academic environment where more than seventy-five percent aren’t even tenured or likely to be, doesn’t in itself make us threatening. When we become obsessed with how much the Right hates us, as opposed to continuing to create work and politics that is actually enormously creative, and radical, and truly dangerous, we have already lost, badly. And, frankly, we deserve to lose if our visions of success are so unambitious and shabby to start with.

When you think you’re a nail, everything looks like a hammer. And all that happens is that you get pounded down a lot.

See also: “A World of Shame: Time, Belonging, and Social Media.”

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

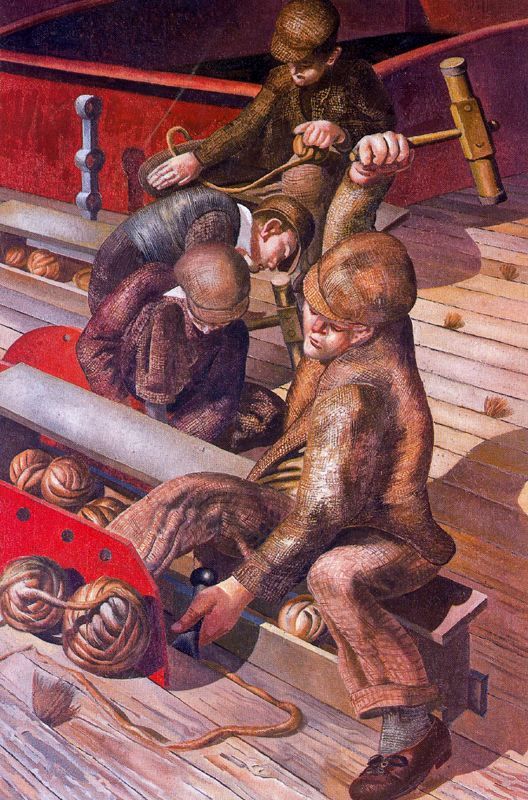

Image: Stanley Spencer, Caulking, 1940