Excerpt: Never Have I Ever normalises her uprooting and her labour …and casts all of it as benign, adorable, and part of the fabric of Indian American life.

If you’re tired of the same old narratives about South Asians—pious families with strict parents and overachieving children, well-off communities living in suburbia, and large families of nosy relatives—Never Have I Ever is unlikely to give you much that’s different. But the Netflix show about Devi Vishwakumar (Maitreyi Ramakrishnan), an Indian-American teen trying to lose her virginity, does at least provide a refreshing look at the reality of what it means to grow up “in two cultures,” as the oft-repeated saying goes.*

Devi is a dork, not the sort of pretty that’s popular in the average American high school, and she’s mired in constant battles with her strict mother. As the first season progresses, we learn that neither has processed her grief at the sudden death of their beloved father and husband Mohan (Sendhil Ramamurthy), an event that both witnessed during a school event. The shock even sent Devi into a temporary and psychosomatic paralysis of her legs. Devi processes her grief by repeatedly getting into trouble at school while Nalini dives into her work and becomes even more controlling, fearful that without her husband to help, their daughter might not continue on her path to second-gen immigrant success.

Never Have I Ever is an excellent time-pass, an Indian term for something that’s entertaining and makes no great demands on you, with the added bonus that North Americans must now learn how to pronounce names like Maitreyi Ramakrishnan. Its central and peripheral characters, including Devi’s two friends Eleanor Wong (Ramona Young) and Fabiola Torres (Lee Rodriguez), have their own individual and interesting arcs, and the episodes perfectly combine weighty matters like grieving—and wanting to fuck the school hottie—with an arch and sarcastic sensibility that directs zingers at all sides of this multi-culti world. John McEnroe, yes, that John McEnroe, is the narrator and the casting choice is a stroke of genius. He appears in one episode towards the end of Season 1, but is otherwise a somewhat bemused yet curious and sympathetic voice, rich with the patina of Queens, able to both marvel at and care about this mixed up teen as she keeps exploding the world around her (and he pronounces “Vishwakumar” with flair). He’s so good that I recommend we institute a special Emmy for each year that’s just an “Emmy For John McEnroe, Narrator, in Never Have I Ever.”

The second season dropped on July 15 and the new episodes delve further into the lives of Devi’s family and friends. The show is still very funny but exploring their issues makes the pace lag a fair bit, except in the case of Eleanor—and that’s mostly because of the manic energy Ramona Young brings to the role. Nalini is now more fleshed out as a person in her own right, not just as a grieving widow, and our glimpses of her in backless cholis and more revealing outfits than in the first season hint that her sex life might be rejuvenated (besides, there’s Common, playing her insanely charismatic colleague and potential love interest Dr. Chris Jackson, so how can it not?). Paxton Hall-Yoshida (Darren Barnet), the boy Devi yearned for in Season 1, undergoes his own changes, going from jock to a student who actually does his assignments. His arc involves his close relationship with his Japanese American grandfather who, it turns out, spent his childhood in an internment camp. While this is certainly moving, it makes the series feel a bit too school-special-y.

While the show is generally passable on, say, queer issues (the school unhesitatingly crowns Fabiola and her girlfriend Prom Queen and Queen), it explicitly slutshames Devi for being with two boys at the same time, something she can only do on the sly in this particular universe, until she’s found out. In 2021, a teenager shouldn’t be ashamed of having multiple sexual interests and should be allowed to express them publicly and with candour instead of leading a life out of a 1960s Rock Hudson and Doris Day film.

Never Have I Ever has other problems, including far too much reverence for India’s genocidal prime minister Narendra Modi, and its ending installs Devi firmly within a conventional romance without questioning the conditions she had to fulfil (including monogamy). Some of the supposed customs are just made up, like Nalini’s mother-in-law Nirmala (Ranjita Chakravarty) oiling the former’s hair after she insists she eat from a plate of food that’s somehow been lying around, even though Nalini has dropped in unannounced. She eats without first washing her hands, which would be considered disgusting in India where there’s a ritualised formality to hand-washing before meals (contrary to what people think, eating with your hands, a common practice, involves preparation and techniques that are more than just pawing through your food and shoveling it into your mouth). As she eats, Nirmala proceeds to give her a hair and scalp massage with coconut oil and that’s just … weird, unhygienic, and unthinkable in any culture (“Would you like some dandruff with that?”). On the whole, though, it’s a genuinely sympathetic and very funny look at the kind of teen we don’t see very often in the U.S.

Still, if it’s going to be any kind of representation of Indian American reality, it deserves to be interrogated on matters concerning a community that has often been stereotyped but also not examined too closely on some of its issues. Chief among these is the problem of elder abuse.

In Season 2, Nalini decides that she needs to return to India permanently, along with Devi. She leaves her daughter in the States and goes ahead to lay the groundwork but once in Chennai realises it’s no longer the warm and comforting place she thought she’d easily re-enter. Her wealthy parents are much too busy to spend time with her — in contrast to Nirmala, who spoils her on every visit. She muses that it might be pleasant to have the older woman massage her head on a regular basis (again, I emphasise, no one in India would do this while someone eats). Nirmala opens up about the fact that she’s lonely, but won’t leave to stay with relatives in Australia because her Chennai home is where she raised her son and “I want to live where [Mohan] lived.” Nalini decides to transport Nirmala back to the U.S with her—after all, that was also Mohan’s home. Devi is surprised but delighted as is Nirmala, who seems to only define herself by her now tiny family and promptly unpacks her homemade pickles—one of the many stereotypes about Indian grandmothers. Devi, having just faced anger and resentment from both the boys she’s been seeing for supposedly having two-timed them and social ostracism from her schoolmates, suggests that her mother should send her off to boarding school. Nalini scoffs: “And pay someone else to raise you? Why do you think I brought your grandmother, then?”

On the face of it, this is a harmless statement offered as a joke, and Nirmala appears to take to her new life without much longing for her old one, despite the fact that she’s moved to an entirely different country where she has no friends or support systems or a job that might provide her a community outside her family. But Nalini’s quip is accurate: Nirmala effectively becomes an unpaid governess to Devi as well as a housekeeper who does the laundry and groceries. She’s cheery and deeply funny and seems well-adjusted. We might expect an Indian woman to try to control her daughter-in-law, but the show goes to lengths to subvert any such cultural stereotypes. When Devi finds out that her mother might be involved with Dr. Jackson, she’s furious at what she sees as a betrayal of her father—and Nirmala slaps her, saying, “Your mother is an adult…she can do what she wants, without your judgement.” (the slap is played for laughs, as it barely grazes Devi’s cheek, but it’s still a slap).

There’s nothing to suggest that Nirmala is in any way unhappy in her new life in a new country, but Never Have I Ever normalises her uprooting and her labour (for which Nalini would have had to pay thousands of dollars a month if she’d hired professional help) and casts all of it as benign, adorable, and part of the fabric of Indian American life.

It’s not uncommon for first generation Indian Americans to bring their aging parents to live in the U.S with them, and that’s often necessitated by the sheer lack of elder care in India. The numbers of the elderly are growing as a relatively young country with a massive population rapidly ages in a time of deepening economic crisis. Indians like to wax on about how they revere their elders but the hard truth is that unless possessed of wealth and resources and in excellent health throughout their lives, many elderly people in India, a country without social security benefits of any sort, are often cast off or neglected and face enormous physical and emotional hardships. Retirement communities are out of reach for most, and the elderly must depend on the kindness and generosity of their children and their spouses. Horror stories abound, of elders being denied adequate food and decent living conditions and of being cut off all from emotional ties to others that might sustain them and ensure their mental health. The problem has only recently begun to be studied and accounted for, as worsening economic conditions make it harder for the average Indian family to sustain a tradition of “joint families,” where multiple generations live under the same roof (even in earlier times, the joint family was hardly a warm and comforting place—contradicting, again, the stereotypical idea that Indians universally treat their elders with care and compassion).

The situation can be a lot worse for elders brought to the U.S, as they’re then completely at the mercy of their children in a foreign country where, even if they know the language, they have no networks of friends, familiars, or community. Many spiral into depression which only worsens their physical health. In the best situations, elders are integrated into, say, church or temple communities or other kinds of support systems, and their children can ensure that they have healthcare with perhaps the added bonus of being close to their grandchildren. Many can thrive, using their situations to find a new lease on life. But research indicates a growing number of cases of elder abuse in U.S-based Indian American families.

A major hurdle in gathering information and data on elder abuse is that Indian elders are loath to discuss their problems with anyone, either out of a sense of shame or because traditional Indian culture (to use a somewhat broad term) does breed a reluctance to discuss family issues with outsiders. Often, elders are just terrified of being punished by their children and their spouses. But, again, horror stories abound: of physical abuse, of elders having their life’s savings taken away from them, of being forced to work as unpaid nannies and cooks and being threatened with homelessness and destitution if they don’t comply, and more.

Never Have I Ever is a fictional show, not a social science study—as such, it’s not responsible for depicting every one of a million nuances of a country with a billion people and the world’s largest diaspora population (18 million, enough to create a country). But representations do have an effect in that they can either highlight or erase people’s realities, and consequently serve to dismantle inequities or perpetuate them. Nirmala is fun, funny, and deeply charming but the show presents what had to be a wrenching relocation and her placement as, in essence, an unpaid housekeeper and nanny—and scalp masseuse—as part of a new and welcome arrangement. It could be argued that several Indian grannies (and grandpas) might actually enjoy their roles, and that their labour gives them a renewed purpose in life. But the research, slowly and surely unfolding, indicates levels of abuse that have so far gone unseen. “Culture” and “tradition” are terms that have a way of insulating communities from scrutiny and Indians (along with other immigrant communities with an emphasis on family) have long used them to excuse away forms of abuse, including corporal punishment (recall Nirmala’s slap).

There is, admittedly, the danger of a whole set of Karens, white or of Indian origin, showing up to poke around and make claims of seeing abuse where there’s none. It’s not as if, say, white Canadian or British or American elders have significantly easier lives and part of the problem is that culture at large has no idea what to do with older people: even the ever glorious Jean Smart is rendered a sexless if quippy grandmother in Mare of Easttown. In an episode of the British mystery series Midsomer Murders, an elderly gent living in a comfortable retirement community explains his short-lived spree of petty crime: he was tired of being invisible to the world. But the problem with elders in Nirmala’s situation is that they’re brought in under an immigration system that doesn’t probe too much into their health and safety because their status is entirely dependent on them being, well, dependents. School-age children might have social workers and teachers looking out for signs of abuse, but no one notices the mostly invisible elder in the family.

In its second season, Never Have I Ever brought in a Muslim Indian American, Aneesa Qureshi (Megan Suri), perhaps in response to criticisms of its Modi-loving ways: change is possible. To ask that the show embark upon a (as yet undeclared) third season where Nirmala decides to return or at least refuses to keep working as an unpaid labourer is to demand explicit social commentary from a series that’s already floundering into school special/diversity training video territory (see above for “ Japanese Internment Camps Were Terrible and My Grandfather Is Living Proof”). The show’s already running out of steam—there’s only so much to mine of a teen’s high school life unless it decides to follow her to college, so this might be the last we’ve seen of it. But, if it were to continue, Mindy Kaling, the writer and brains behind the show, is hardly without talent and has always demonstrated a knack for making a point without beating people on the head with it: she and the writers could step outside the Indian Granny Zone and let Nirmala fly free and not just on the wings of slyly caustic comments.

Imagine: Nirmala returns to India, leaving behind a mountain of unwashed laundry and dishes. Nirmala rescues a fellow granny from her exploitative family and sets up a detective agency specialising in missing or abused elders. Nirmala retires somewhere with a view of a lake and paints all day. Nirmala spends the rest of her days traveling the world and hooking up with random lovers. Who knows? The possibilities are endless.

***

*A note on criticisms of the show: Never Have I Ever is created by Mindy Kaling and Lang Fisher, and the former is widely credited for increasing Indian American representation on American television. Some critiques of Never Have I Ever, like this one by the Canadian Indian actor Lisa Ray (who calls herself a “Global Indian”) point to “tired ethnic stereotypes” and “bad Indian accents.” As I dove into several such criticisms, I couldn’t help notice that, overall, the complaints were on the lines of “my Indian diaspora friends/cousins and I don’t talk with such accents” or “arranged marriages among contemporary Indians are very different, and involve more choice” (Devi’s cousin Kamala, a student at Caltech, is nudged into one, and she literally runs away from it) or “Kamala is much too unsophisticated to be an upper class Caltech grad.” There was a distinctly class-based thrust to many of the critiques.

125 million Indians speak English, but that’s only ten percent of the population and there are a million different accents depending on region and other factors; I doubt that critics know what every Indian accent sounds like. Accents can range widely even within families (just as they can in, say, an average non-immigrant family of any colour in Illinois). In a country of a billion, the range is almost infinite. While the critiques are not entirely without merit (I suspect the show evolved a particular Indian accent just to make things more coherent for an average viewer), they mostly emerge from upper class Indians or Indian Americans who are proud of their grasp of American culture and life and seem to hate the idea of being associated with certain accents or a lack of sophistication: it’s hard to miss their combination of shame and annoyance.

There are also criticisms that the show reflects an older reality unlike what contemporary Indian Americans experience, especially with regard to Hindu rituals (Devi’s family goes to temple often). But, again, according to whom? Plenty of millennials are raised to go to Hindu temples regularly, and it doesn’t make them right wing. At the same time, the rise of a deeply consevative Hindu Right within the Indian diaspora also means that, in fact, quite a few arranged marriages erase choice altogether (and many don’t, yes). And while Lisa Ray, born in Toronto, may have grown up in an urban environment, plenty of Indian Americans or Indian Canadians grow up in small towns or suburbs and even cities where they’re lucky to have a single Indian restaurant. This doesn’t make them less sophisticated or worldly (if we think that’s an important characteristic for a human to possess), just that their formative experiences are different and some of those are reflected in a show that can’t possibly include every single one of the millions of experiences of being “Indian” (Kaling herself grew up with a fair amount of privilege in Cambridge, Massachusetts). The show can certainly be criticised: I just wish that critiques so far didn’t simply replicate the desire of a certain class of diasporic Indians to assert their own sophistication and urbanism.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

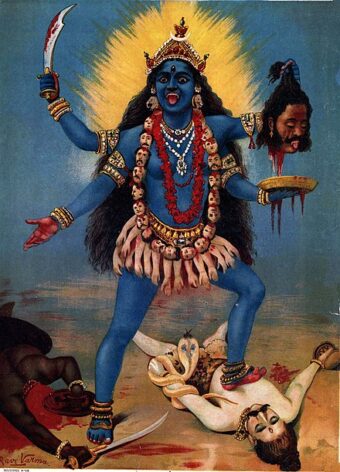

Image: Kali, the Destroyer.