One of the big stories this season is unrelated to shopping or entertainment: food pantries across the country are facing drastic shortages in items donated from the agricultural industry. This means that more people who depend on food pantries will go hungry this year. One simple set of numbers drove the point home: donations to food pantries are down 30% while demand is up 40%.

I’m struck by the focus on the decrease in food donations. What concerns me is not the 30% dip in donations, but the 40% increase in demand. What concerns me is not the hunger, but the poverty that causes the hunger. What concerns me is our emphasis on and hand-wringing over feeding the hungry while we continue to ignore the systemic problems that cause the kind of poverty that forces people to wait in line for food.

According to a piece by César Chelala, “33 million Americans continue to live in households without an adequate supply of food.” 13.9 million children experience food insecurity, 3 million experience actual hunger. The differences between these terms seem hazy – something like the difference between the moment you’re teetering on the edge of a cliff as opposed to simply falling off it. But the point is that too many people, including children, face perennial anxiety over something as basic as food — in the world’s richest country. I don’t ordinarily use statistics about children because, let’s face it, most stories about them deliberately play on cheap sentiment and work on the assumption that people with children are somehow better and more noble (for more on that, see, well, nearly everything I’ve written here). But in this case, there’s one painfully obvious fact that makes it necessary to raise the issue of children: without adequate and proper food, they’re not likely to grow much or at all or particularly well. If there’s a 40% increase in demand for food at pantries, there are more adults and children than last year who are in dire straits. Something is going badly, sadly wrong.

And everything that “we” do to alleviate the problem of hunger only extends the conditions of poverty.

Part of the problem is that we’re willing to think about “hunger” more than we’d like to think about poverty or inequality. “Hunger” is something we think we can solve by giving food and serving soup, but poverty and inequality are tied to systems we’d rather not question – even when we find ourselves ensnared in them. Even our realisation of how many of us are actually affected by poverty and inequality becomes just another way to create distinctions between the good poor and the bad poor. In case we miss the point, news reports about the current shortage are careful to point out that “The homeless are only 9 percent” of those served. “Forty percent of the people who get food…have jobs…22 percent live in the suburbs.”

When we speak about the poor, we attach qualifiers to ensure that everybody knows we’re talking about the good kind. So we use terms like “working poor.” What we really mean by such phrases is to distinguish between the useless bums, the crack addicts, the derelicts – and the deserving poor. It reminds me of that other term, “working families.” Which is another way of saying: there are entire families that work and entire families that just lie around and expect handouts all day long. But what’s the point of valorising some people as working poor or working families when their work barely earns enough to pay the bills and buy food? What – and who—is served by such terminology? The issue shouldn’t be about whether or not we can bring ourselves to like some poor people over others – or even whether we should have to “like” poor people, period. We should be far more concerned about ending the conditions that produce poverty.

It strikes me that everything this season is about reinforcing these sorts of distinctions between the good poor and the bad poor, between them and us, even when “we” might actually be the people we’re asked to help. Give, we’re admonished by the Salvation Army person with that bell, and by any number of people on radio and television. In response to the food pantry crisis, one local grocery chain has taken to leaving out giant boxes for people to fill with donated goods that they can buy at the store. At the checkout counter, clerks will ask if you’d like to make a donation – try saying no to that with a line of people behind you. This is all couched in the rhetoric of “communities” coming together to help their own, but it’s also about equal parts shame and public glory. Such tactics depend on some tried and true marketing strategies, including the all-important “how do you explain it to your kids?” question. What do you do if your kid sees a giant box for food donations? How do you explain to her that there are others like her who might go hungry in this season? That familiar scene is supposed to play out over and over again in the store. But here’re some questions that could also be asked: What do you do if you’re one of those who lives perilously close to being hungry and homeless? How do you explain that to your kid? How do you explain her own poverty to her?

A Chicago PBS segment on the food pantry story featured shots of a massive and obviously very tall warehouse, with rows and rows of shelves. The point of the shot was to emphasise the many empty shelves. When the real point should have been to emphasise the fact that there are in fact many empty shelves. That we now have an intricate food distribution system that requires warehousing, one that’s designed to feed the hungry, should not be a point of pride. And yet, so many of those who are now part of the industry of food bank depositories fail to see the contradictions in their work. Food donations are not community-based support systems that come into place during emergency situations; they’re now part of an industry. This is especially clear in Sarah Miles’s Take This Bread: A Radical Conversion. Miles writes about how she became the founder and director of a food pantry at her San Francisco church, St. Gregory’s. She’s proud of the fact that St. Gregory’s feeds even the undocumented but fails to see the extent to which her enterprise is also part of the system that perpetuates the poverty that drives her clients to seek food.

Consider the details of the San Francisco Food Bank (SFFB) where St. Gregory’s gets its supplies. We see the tip of the iceberg when its executive director tells Miles, “We’re simply a part of the market.” And how. SFFB gets food from the giant corporations, called agribusiness, that have taken the place of independent farmers across the country. In exchange for its donations to food banks, agribusiness gets tax write-offs. Those write-offs help make it more profitable. More profitability makes it harder for workers, especially migrants, to unionize or demand fair wages. That creates more poverty and more underpaid labourers, who line up at food pantries like St. Gregory’s. Which work with enterprises like SFFB, which work with agribusiness. Leaving agribusiness free to continue bad labour practices.

And in case you still think I’m just being a grump and a grinch, consider the coda to the food pantry shortage story. Guess who came to the rescue, along with ConAgra? Walmart.

The same company that makes it difficult for workers to demand better wages has just donated “$1 million worth of food.” What might be the chances that Walmart workers will need to line up at food pantries that receive donations from Walmart?

Be scared. Be very, very scared.

Don’t mourn, organise, goes the old injunction. Perhaps another one is now required, more apt for this neoliberal age where charity is seen as a solution when it should be recognised as the problem. So here’s one: Don’t give, agitate. For better wages, for health care, and for eventually phasing Food Depositories out of business.

Happy Hols, everyone.

For more, see my review of Take This Bread, by Sarah Miles.

See also, “On Giving, Money, and the Left.”

Originally published on The Bilerico Project, 25 December, 2007

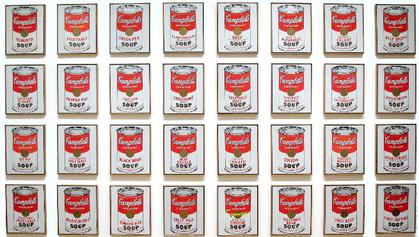

Image: Campbell’s Soup Cans, Andy Warhol, 1962, photo by Hu Totya .

If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” Don’t repost this anywhere, in translation or in the original, without my permission.

If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.