About two centuries ago, I began the process of applying for a Very Big Grant. I was working with an advisor on the document but thought it would be useful to have some kind of a model to look at, so I asked a previous recipient if I could look at their proposal (grant applications can be terrifyingly complex). The response I got was a shock, not only because they declined but because of the vehemence with which they responded, with words to this effect, “No, I’m not sharing it with anyone, because no one helped me when I was working on it.” I nodded politely with something like, “Sure, I understand,” and went back to my work.

I got the grant. The first thing I did was to take my successful application down to the office and ask that they create a file with all such proposals so that others, in the future, might have them as reference points. That was, as I’ve noted, many years ago (and research currents have changed vastly since then), and I have no idea if the file still exists but it felt important at the time to ensure that people coming after me had a different experience, that they not feel quite so lost about the process.

The point here isn’t how good I was in comparison to the other person: over the years in academia, I’d absorbed enough about it to know how brutal, isolating, and even dehumanising it could be and people respond in different ways to the adversity and harshness they face. I was startled by the ferocity of their response, sure, but I could see why they responded that way. Or, well, I like to think, now, a couple of hundred years later, that I had it in me to be that understanding. I don’t recall feeling anger towards them, just—and I know I keep returning to this word—shock. I suspect—or hope—that they’ve moved away from that place of bitterness. What compelled them to respond the way they did wasn’t some innate part of their nature, but a compulsion born of a system that had left them feeling alone and angry, cut off from the kind of support they needed. Part of the reason I was so startled was that they had always been among the nicest people I knew, always helpful and kind and willing to talk to a junior like me. I suspect they still are.

What mattered to me at the time was that my own response in turn should be different. Not because I wanted to be a better person or even a good one, but because I wanted a better structure for everyone else after me. What impelled me to do what I did was—again, that word—the shock of the anger and resentment I felt, and the sense that I wanted less of that in the world.

We should want better lives and worlds for the ones after us. I think of this often, sometimes in private interactions or when I reflect on the horrifying systems into which we’re all thrust. When friends of mine go through humiliating and demoralising experiences with their superiors, my advice, once we’ve worked through how to get them out of such situations, is always, “Just remember: the best way to deal with this is to make sure you never repeat this behaviour with your own workers/students.” My worry is always that the hurt and the anger might replicate themselves down the line. And who can blame us for harbouring anger and resentment and more? The world and a lot of people in it seem to thrive on recreating cycles of spite and worse. Even now, in what looks like a golden era of academic unionising, such efforts still face hurdles from faculty and adjuncts who hiss that they want no part of the process because, “I put in my time, and I don’t see why others should reap the benefits.” The student debt cancellation movement is thriving, thanks to the efforts of groups like Debt Collective, but there are still so many who sniff and sneer, “So, I had to spend decades paying down my debt and these people get to waltz in and have their debts cancelled?” Online, of course, it’s all much more toxic and even putrid. In response to someone scoring a literary contract, several trolls opined, “He should have to do what the rest of us did, and first work at crap jobs like I did.” (That most of them are lying because, trolls, is perhaps besides the point.)

There isn’t an adequate response to such meanness, except to consider how our world is scarred by the effects of several overlapping mythologies about scarce resources and how that, in turn, makes us all ferocious about a prospective future that may in fact be already denied to us. This is the logic that the financial world thrives on: that there’s only so much money in the world, and if we let everyone have more, there won’t be enough for everyone and we will all starve and die. Much of this thinking is, of course, echoed by people who regularly escape to whatever version of the Hamptons might exist in their states. But, yes, actually, it’s fine if many millions of people will be freed of their crushing debts and able to live joyous lives filled with more leisure and time to do nothing at all, if that’s what they want. We could learn a lot from some former prisoners, including many who spent decades in cold, dark cells and who still emerge, even when so utterly broken, determined that there should be no more prisons for anyone else, ever. (Of course, anyone who emerges in a different frame of mind from the horror of imprisonment is entitled to their opinions and feelings.) We could also learn a lot from climate activists and writers, most of whom may not live to see the world they help to save even as we teeter, smoke filling our lungs, on the edge of disaster.

I think of my own past career in writing. I can remember the times when I shuttled across the city, covering one event after the other in a single day, as many as I could to make enough for groceries that week, rent that month (barely), returning home exhausted to make sure I got multiple pieces in on time. Did I learn a lot about journalism and writing quickly? Yes, sure. But, bloody hell, there are other, better ways to learn all that and I don’t wish it on anyone else. My utopia is one where, perhaps fifty years from now, I’m at a party and, slightly buzzed from my excellent glass of wine, I start telling a group of much younger writers about my work conditions “back in the day,” and they all stare at me with both bewilderment and amusement: “Wait, are you saying that newspapers were not all well funded so that they could pay everyone a living wage? Wait, what do you mean, everyone was a, what’s that word, freelancer? And you had no rent control?” And I pause and realise, “Ah, yes, this is all just long ago history to this lot…and that’s fine, it’s all fine,” and then I leave and enter the night, the cold crisp air enfolding me in its arms.

And behind me, one writer turns to another, “Was she kidding? Did all that really happen then?” And the other shrugs, “Yeah, I think I read about it in a journalism class. I mean, she is nearly three hundred years old, though, so who knows.”

Everything we do, we do for the ones after us.

For more on what a utopian world might look like, see Nathan J. Robinson’s Echoland: A Comprehensive Guide to a Nonexistent Place.

This piece is not behind a paywall, but represents many hours of original research and writing. Please make sure to cite it, using my name and a link, should it be useful in your own work. I can and will use legal resources if I find you’ve plagiarised my work in any way. And if you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

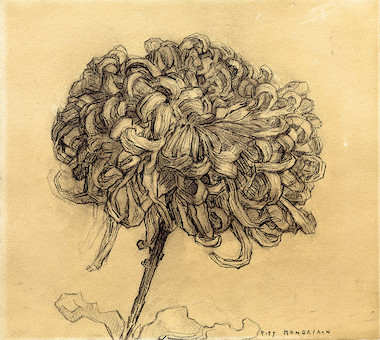

Image: Piet Mondrian, Chrysanthemum, c. 1908.