It also reflects the cultural identity of an art world that can no longer afford to take any real risks.

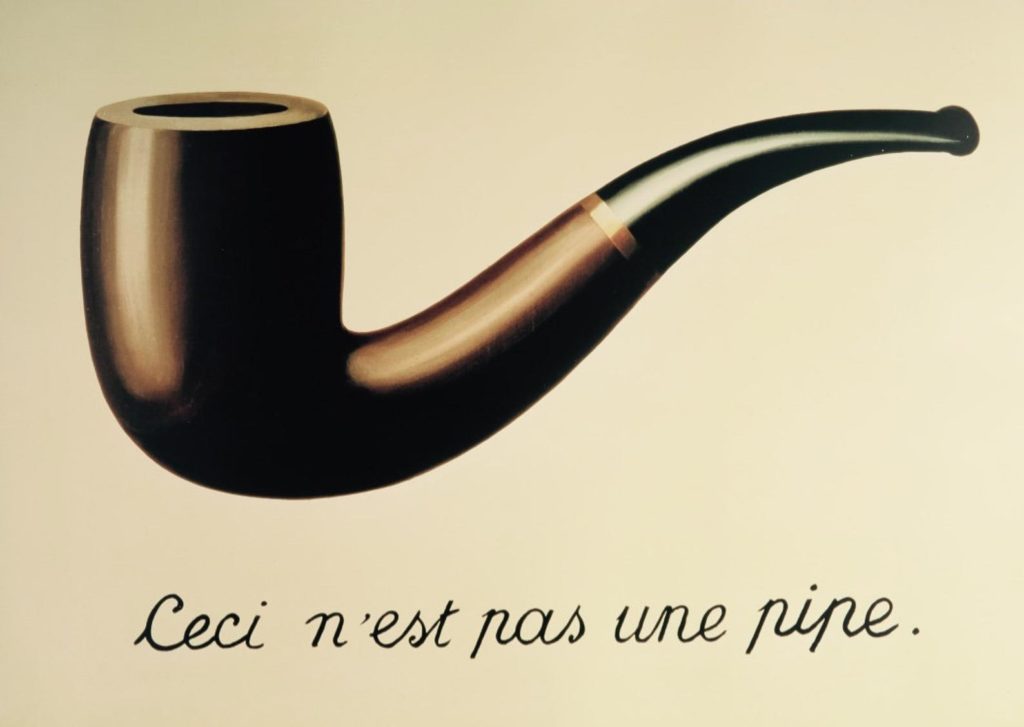

Like perhaps millions of people, or at least tens of thousands, I finally watched the new video and performance art piece by Emma Sulkowicz, Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol, French for “This is Not a Rape.” As any freshman art student and anyone reasonably acquainted with even a smidge of art history can tell you, this is in part a reference to Rene Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe). Which, in itself, is situated within a long gestural history of art-making and representation, and so on.

The video is about eight minutes long, and is a brief re-enactment of the sequence of events described by Sulkowicz in her claim that she was raped by a fellow student, Paul Nungesser, in her dorm room in August 2012. It appears on a site that includes a set of instructions and exhortations by Sulkowicz, directed at the viewer. For instance: “You might be wondering why I’ve made myself this vulnerable. Look—I want to change the world, and that begins with you, seeing yourself…” “If you watch this video without my consent, then I hope you reflect on your reasons for objectifying me and participating in my rape, for, in that case, you were the one who couldn’t resist the urge to make Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol about what you wanted to make it about: rape. Please, don’t participate in my rape. Watch kindly.”

Sulkowicz’s new work is firmly embedded in a long and compacted history or, really, a set of histories that sometimes intertwine and sometimes shatter on contact. There’s porn, for starters, especially of the “amateur” sort, often set in antiseptic and cramped dorm rooms whose very sterility provides a contrast — and added excitement — to the featured sex.

There is feminist art, of course, in which Sulkowicz has already staked a claim, as this somewhat protracted and quite unendurable conversation between her and New York Times art critic, Roberta Smith, who wrote a piece about her for the paper, indicates.

In the video, Sulkowicz can be seen going down on the male actor (whose face is anonymised), and I couldn’t but think of Chloe Sevigny, who did the same with her then-boyfriend and director Vincent Gallo in The Brown Bunny. The scene created a sensation at the time, prompting questions also asked of porn: Is this real? Does she really take his cock in her mouth? Sevigny’s performance left no doubt (and there was a question of whether or not it really constituted a performance after all) and the drama between real life and fiction cemented the reputation of an otherwise boring director who, much like Sevigny herself, makes waves for who he is and not for what he does.

There are specific art pieces we could think of, like Tracey Emin’s My Bed, which recently sold for $4.3 million. There has been some discussion of whether or not Sulkowicz’s famous blue mattress might become a museum piece.

There will be, following this video, reams of discussion about whether or not this new work is art or not, or whether it counts as good or bad art. There will probably be an entire journal issue devoted to Sulkowicz, with many critics weighing in on the nature of her work, the merits or lack thereof, and so on. At the very least, Sulkowicz is assured of a career for the next twenty years. It may not be as an artist, but she will doubtless become a popular figure on campuses as generations of students flock to hear her speak, a Gloria Steinem without the political history (whatever you think of Steinem’s politics, at least she has had a history).

For someone with an exclusive and expensive Manhattan education, entirely in private institutions, Sulkowicz is surprisingly incoherent and inarticulate in interviews. My comment will no doubt seem both classist and sexist. After all, many might insist, she’s an artist, and she doesn’t have to be able to talk about her art, she just has to make it. And in a time when we fetishise “real” speech and words as authentic and decry “academic” erudition as jargon, what right do I have, many will demand to know, to insist that someone should actually be able to talk about her work?

But, well, except that she’s an artist emerging from a very privileged background and a graduate of one of the most cerebral art programs in the world. Its students aren’t just trained to “make” art but to explicate it, sometimes at pedantic and boring length.

I don’t raise the incoherence of Emma Sulkowicz to mock her. The simplicity of her work and her inability to connect the dots and the fact that her text comes laden with so many directives is all symptomatic of the nature of her work, which emerges from a cultural DNA comprised of social media vectors and synaptic breakdowns. Sulkowicz’s “work,” such as it is, is less a piece of art she crafts on her own and more a stammering, stuttering coalescence of talking points, a mish-mash of political statements culled from generations of feel-good feminism. It also reflects the cultural identity of an art world that can no longer afford to take any real risks.

Take her trigger warning, inserted at the beginning: “The following text contains allusions to rape. Everything that takes place in the following video is consensual but may resemble rape. It is not a reenactment but may seem like one. If at any point you are triggered or upset, please proceed with caution and/or exit this website. However, I do not mean to be prescriptive, for many people find pleasure in feeling upset.”

Along with her commands posted earlier, the text, without the video, simulates a number of media vectors while simultaneously and self-consciously parroting an art-school ethos, alongside some pragmatic asides. She claims it’s not a re-enactment, which is partly a comment about the nature of the text — but it’s also a clever way to place a legal loophole in place: Nungesser cannot, theoretically, now sue her for literally misrepresenting what happened. The fact that the video will not always play could be a result of too many people trying to access it, but it also succeeds in creating an audience that keeps returning to it, a built-in guarantor of hits, so important for a digital age. The trigger warning, of course, is perhaps the clearest sign of a generational impasse, a state of things where instructors must now worry about traumatising their students by simply assigning texts. It’s also the beginning of the end for an art world which can now no longer afford to challenge viewers, but must tread on eggshells and prepare for delicate sensibilities that might not be able to face unpleasant representations of, oh, war, rape, and genocide.

I can see a way to make a statement about all of this, and I can see how all of this could be mistaken for dazzling brilliance. There is, to some eyes and minds, so much referentiality packed in that, surely, it must be brilliant because it says so much and we can’t really figure out what.

The problem is that there are actual people involved in all this. What does it mean for something to pose as a work of art, even “political art,” with all its didacticism, when there is an actual lawsuit and the question of guilt versus innocence, to consider? Nungesser, in filing suit against the university and Sulkowicz’s art professor, has released the content of texts which are far more damning for her. What if he played an endless loop of her words, including the ones where she implores him to “fuck me up the butt” and declares her love for him, after the alleged rape, alongside a similar re-enactment? Would that have the same reception?

What does it mean for Sulkowicz to create work that gets consumed on the same vectors as online porn? If she does sell the bed to a museum or to a collector, should we be concerned about who might end up owning it? To return to My Bed, what does it mean that the piece was sold to benefit the Charles Saatchi Foundation, run by a man who was photographed half-choking his partner Nigella Lawson in a restaurant? Are those even legitimate questions? Or do we shrug and say, well, an artist has to do what an artist has to do?

For the record, I’m not anti-porn and I don’t think artists, especially American artists who are severely underfunded, should have to worry about whom to sell their art to on top of worrying about whether or not it will sell.

But if Sulkowicz is going to present a potential viewer with so many questions, surely viewers have a right to turn the tables on her and ask a few of her in turn.

That leaves us, of course, with the eternal question: But is it art?

That, Dear Reader, is a question I leave up to you.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.

Image: René Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe, 1929