Excerpt: It’s not that anal sex disrupts capitalism… but that it symbolises the dichotomy between public and private which also characterises the accumulation of capital.

In the Fall of 2014, Emma Sulkowicz began what has now become perhaps the most famous art school project, titled Mattress Performance/Carry That Weight. Sulkowicz, a visual arts major at Columbia University, went everywhere till graduation this year hauling a navy blue, full-size mattress.

According to Sulkowicz, she was raped by fellow student Paul Nungesser in 2012, on a mattress identical to the one she carries around. She describes Carry That Weight as a representation of her ongoing trauma. Her aim, she says, is to continue the project until one or both she and Nungesser graduate or until he is driven out of the university which, she claims, has failed to protect and grant her justice.

At the heart of the story is her account that Nungesser suddenly grabbed her during a session of consensual sex, pinned her down by her legs, and raped her anally. I will leave any discussion of the merits or demerits of the case for a later piece. More details about it can be found here and here.

What interests me is the issue of anal sex, a factor in this case which has so far gone unremarked upon but which is an important reason why her story leapfrogged its way into national and international headlines.

I suggest that any other form of sexual penetration would not really have been as compelling and that the matter of anal rape is a major reason for the interest in Sulkowicz’s allegations. If we consider her story only in terms of her alleged violation, it can be read as an account, even a disputed one, of anal rape. But if we consider it in terms of the issues raised about the distinctions between public and private spaces, Sulkowicz’s performance and story emerge in a different context altogether, of anal sex and the role it has played in the constitution of the mainstream gay community.

In the US, the supposed striking down of the sodomy law Bowers vs. Hardwick came about with Lawrence v. Texas in 2003, the case that allowed the gay marriage movement to continue with its legal cases and reach a point where gay marriage is now an inevitability. Without the striking down of a sodomy statute, no gay marriage case would have had a chance.

If we only consider Lawrence v. Texas in the way that Lambda Legal has characterised it, as a case that meant that “No longer can gay people be considered ‘criminals’ because they love others of the same sex,” it might look like a legal hurdle that was overcome by brave and persistent gay men and their lawyers in the interest of true love torn asunder. In fact, as with Sulkowicz’s case, the element of anal sex played a role, even though never described but implicitly portrayed as an act of love carried out in private. At the time, cartoons like this one echoed the dominant cultural discourse at the time, which emphasised what were assumed to be central facts of the case: that two white men were intruded upon in the privacy of their home while engaged in anal sex.

While Lawrence v. Texas came about at a particular moment in the mainstream movement towards what is often described as gay rights, Emma Sulkowicz’s story emerged within a furious debate about the extent of what is being described as “campus rape,” an issue which has recently been embroiled in even more controversy after it was revealed that the most sensational story so far, about an incident on the campus of the University of Virginia, was untrue.

But none of that fully explains the support and rancour she has whipped up against her alleged rapist. What makes hers so much more a case of public discussion is precisely that she has situated it within the distinctions of public and private and linked her story of anal rape to a narrative about having her privacy and sense of safety severely violated.

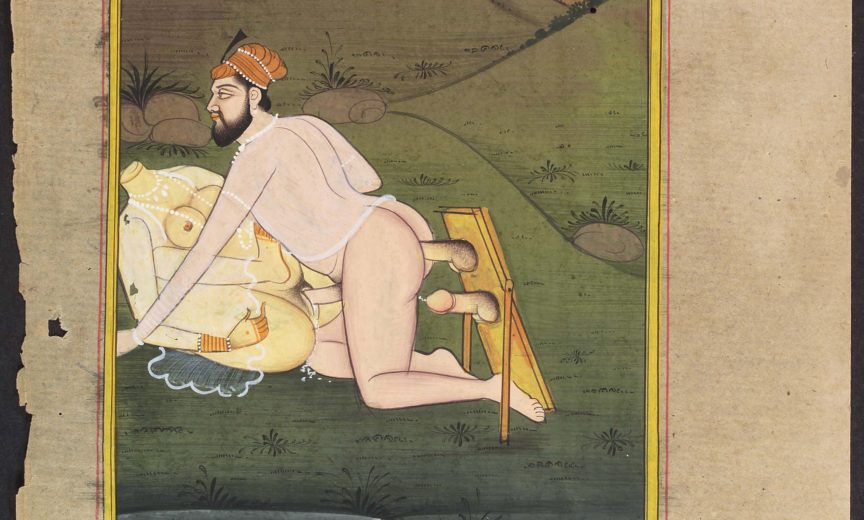

To see how this played out in a cultural context where anal sex and discussions of it are now seen as “sex-positive” or where anal sex is seen as positively transgressive and daring, it’s worth considering the history of the act as a cultural narrative that defines women’s propriety or lack thereof, a narrative which has played out with similar meanings across cultural borders.

In 2004, the former ballerina Toni Bentley published a memoir, The Surrender, about her adventures in anal sex. At the time, the phrase alone could still elicit twitters and giggles (Twitter was not yet a proper noun). Today, with Kim Kardashian’s ample bottom posed on the cover of an art magazine like Papermag and mainstream women’s magazines providing tips, the idea of a woman’s asshole being penetrated and, more importantly, the idea that women might actually want to partake of anal sex and enjoy it, appears to be practically passé.

But there is still a degree of stigma and shame attached to the idea of women engaging in voluntary anal sex, and this has been true for a long time. Anal sex has been considered something good girls and women never do, strictly the province of gay men and prostitutes. Even going back just a few decades: One of the most notorious texts of the AIDS era was an essay by Robert E. Gould in the January 1998 issue of Cosmopolitan, claiming that straight women were incapable of contracting HIV because their vaginas were too rugged to let the virus in. Engage in anal sex, though, and all bets were off because the anus was too “fragile” to stop the virus.

In most cultural representations, anal sex is portrayed as the most demeaning act, a particularly brutal form of punishment. The film Bandit Queen, about Phoolan Devi, features many gratuitous scenes of rape, and one of the more explicit ones shows her being gang-raped. Towards the end, one of them laughs about her taking it from behind. The camera cuts away at that moment, as if somehow that alone was so inexpressibly horrific that it could not be shown, even in a film that otherwise exploits her multiple rapes.

When asked by Marie Claire magazine in 2009 how women might make anal sex more pleasurable, Dr. Drew, who plays a sex therapist for a gullible public, ranted that it is never anything women should do, warning of dire consequences like “leakage,” disregarding the millennia of experience that gay men, for instance, could draw upon to prove the contrary.

In short, while it is doubtless that anal sex between men and women has been going on for as long as sex itself, the larger cultural narratives about the act still mostly define it as something that only not-nice girls do. Or, and this is the crux of my point, as something that can only be forced upon nice girls, during rape.

To think more probingly, if you will, about the history of anal sex for women requires us to think about the history of the homosexual who, as Foucault and others point out, had to be invented in part to begin a complicated regime of sexuality. That particular thesis is frequently misread by essentialists like Larry Kramer as a claim that there were literally no homosexuals before a particular moment in history. They miss the point that the fact that there have always been homosexual men performing homosexual acts and who have been in homosexual relations with each other is separate from the ways in which homosexuality has shifted in legal terms over the years. The thesis about the invention of the homosexual does not imply that there were no actual homosexuals prior to a particular period in time but that the framing of “the homosexual” as a legal entity that could be scrutinised, examined, barred, and legislated, sometimes literally to death, is a relatively recent phenomenon. It is no accident that state crackdowns on homosexuality or those perceived as homosexual have involved anal probes and rapes, that some of the most infamous cases of police brutality have involved sodomising men with foreign objects.

Proscriptions of anal sex, as an activity engaged upon by homosexuals and therefore defined as an illegal act could, theoretically, be used to imprison heterosexuals as well but they have historically been used to persecute and prosecute gay men and any others defined as “deviant.” If we consider the legal definitions of sexuality only within the terms of sex, as straights and too many gays are too often wont to do, we lose sight of the ways in which the definition of sex is in fact tied to larger questions of property, lineage, and wealth and its distribution.

Ultimately, anal sex carried with it not only the stigma of revulsion, but that of being a non-procreative act, something that does not support the creation and construction of what the state defines as legitimate estates and property. It’s not that anal sex disrupts capitalism, although some sex-positive theorists might well claim it does, but that it is symbolises the dichotomy between public and private which also characterises the accumulation of capital.1

We can see this most clearly when we take a more careful look at the celebratory discourse around the supposed striking down of the U.S sodomy law, Lawrence v. Texas in 2003.

Lambda Legal was among those who hailed this as a “ stunning victory,” but skirted around the main point of the ruling. As its own press release reveals, “lesbians and gay men share the same fundamental liberty right to private sexual intimacy with another adult that heterosexuals have.” The sticking point here is the phrase, “private sexual intimacy.” You can bugger anyone you like, as long as you do it in the privacy of your own bedroom. But take it outside to, say, a bush in your local park or the bathroom of your favourite bar, and no one, certainly not the lawyers at Lambda Legal, will come to your aid.

As my report on sex offender registries indicates, sodomy laws still exist in full force. Richard Yung points out that “crimes against nature” laws persist. The difference now is that they will not be used against married gay men or couples who have money and estates to leave each other, but against the most vulnerable. In one Virginia case, two minors, both male, around 15 years old, were prosecuted for sodomy: the courts decided Lawrence v. Texas couldn’t apply because they weren’t consenting adults. In addition, street-based sex workers of any sexual orientation and/or gender identity are liable to be prosecuted under sodomy laws precisely because they commit their acts in public spaces. They also run the additional risk of becoming registered sex offenders.

All of this has been ignored by the mainstream gay movement, and to date Lambda has not taken a stand against sex offender registries, despite the fact that queers — not the “respectable sort” — are routinely targeted, harassed, and placed on them. The fine points of Lawrence v. Texas have been pushed into the background in favour of painting it as a case of love torn asunder because the case performed what was, to mainstream gays, a far more important function: It allowed for gay marriage cases to proceed. As long as a sodomy law remained on the books, gay marriage appeals had no standing.

But among the several lesser-known facts about Lawrence v. Texas is that there was no anal sex involved, and that one of the defendants was black and the other white, which probably accounted for why the Texas police were so eager to arrest them both that night. As the New Yorker’s Dahlia Lithwick puts it in her review of Dale Carpenter’s book on the case, Flagrant Conduct:

…the case that affirmed the right of gay couples to have consensual sex in private spaces seems to have involved two men who were neither a couple nor having sex. In order to appeal to the conservative Justices on the high court, the story of a booze-soaked quarrel was repackaged as a love story. Nobody had to know that the gay-rights case of the century was actually about three or four men getting drunk in front of a television in a Harris County apartment decorated with bad James Dean erotica.

In a very particular and paradoxical way, the absence of anal sex was retold as a presence and as a story of true and romantic love and eventually paved the way for gay marriage to become legal. But the success of the case relied on the spectre of anal sex: Uppermost in American minds was the private scene of two (white) men buggering each other. Given the racist legacy of social organisation in this country, where black-white inter-racial relationships, in media or real life, are still controversial, it is not difficult to speculate that the widespread knowledge that one of them was black would have meant far less sympathy for the defendants.

All of this was the context around the ultimate decision. What the Supreme Court did was not to strike down a sodomy law, but to assert that sodomy was allowed under very particular circumstances.

Anal sex thus plays an invisible but potent role in the gay marriage movement. Gay marriage proponents and their straight supporters love to paint their “battle” for “equality” in terms of love, and deride the Right for denying gays and lesbians the right to form affective bonds of intimacy. Yet, they also conspicuously leave out what that intimacy might actually entail, preferring instead to focus on images of devoted gay men and women whose beautiful and perfect children, often adopted from far-away lands, magically materialise to testify to their parents’ devotion. The spectre of anal sex, once a potent if misplaced reminder of AIDS, has been summarily wiped out from the cause of gay marriage. Historically, even when part of long-term relationships that sometimes spanned decades, many gay men have been non-monogamous and constructed lives and kin groups that include current and former lovers and a host of people who rarely comprised what we might understand as “normal” families. Today, even a hint of such alternative lives is quickly dismissed for the sake of providing acceptable gay role models.

The success of the gay marriage movement depends entirely on what is ultimately a stroke of genius: Eradicating the very idea of sex from its vision of marriage.

The success of the case against Lawrence v. Texas depended on a similar paradox: Drawing upon a distinction between public offenses and private sexual acts, even as the original moment which led to charges against the two defendants included neither.

This distinction between the private and the public is also linked to anal sex in Sulkowicz’s claims and performance. In a video, Sulkowicz describes her project as something that grapples with the space between the public and the private. She describes the role of beds: “We keep them in our bedroom[s], which [are] our intimate space[s], our private space[s], where we can retreat…I think in the past year or so of my life has been really marked by telling people what happened in that most intimate private space and bringing it out into the light, [the performance] is supposed to mirror the way I’ve talked to the media…”

In that, she echoes the underlying logic of the Lawrence v. Texas case, that sodomy could be private as long as it remained in the bedroom. There is of course a crucial difference between the discussion of anal sex in that case and hers, which involves an account of rape, and the charge of anal sex comes from her, not from an outside agent. But as with Lawrence v. Texas, it is the allegation of the act that makes it possible for her to create the public/private distinction so strongly.

Even today, in 2015, a rape victim’s credibility depends upon the extent to which she can prove her status as a perfect victim. Sulkowicz, a sexually active and elite New Yorker — as well as a multi-racial woman — would have had much less chance of proving her case in the public eye than if she had been a white, middle-class young woman fresh to the sexual currents of college life. If she had claimed any other kind of sexual assault, she could have faced accusations or doubt much more forcefully: Was she perhaps drunk? Was the sex perhaps actually consensual? It is the alleged fact of anal rape which allows for the incident to be cast within a narrative about the violation of private space necessitating a public demand for justice (Sulkowicz spoke to the press after Columbia ruled in Nungesser’s favour).

Casting it as anal rape leaves no room for doubt because the cultural reasoning is simply that a woman could never have consented to the same.

This does not, of course mean that a woman who asked for anal sex could not also have been anally raped, even at and in the very the moment of the sexual encounter. But in evoking the spectre of anal sex, the anus re-emerges as a site of untarnished and unpenetrated site of non-pleasurable sex, the ultimate zone of privacy literally torn apart.

What both Lawrence v. Texas and the Sulkowicz case show us is that all of our sex is historical, always interpellated into legal queries and documents and public speculation and always, at any point, poised to become part of a larger set of cultural and legal codes. There is no such thing as a “private” sexual act. And there is nothing about sex that is not laden with external meaning defined by the law: Every caress, every single motion, every single gesture is already encapsulated in legal definitions. The fact that we possess a vast corpus of literature on the romance and allure of sex (or that we have entire memoirs devoted to particular acts) can never serve to dissociate sex from its legal functioning and its complete implication in laws defining property and the value of houses, people, and children.

In years past, gay men were compelled to adopt their male lovers to ensure that they could inherit the property they left behind. There is no reason to value that time as some idyllic past, but marriage, embedded within the narrative of true love is not the answer to how queers might redistribute their often scant resources to the ones they care about. Today, gay men can assume their spouses will enjoy their estates uncontested, but what of those who have no desire to partake of the institution of marriage? Marriage is becoming the overwhelming response to a litany of problems, allowing the state to retreat from its role in the welfare of people. No healthcare? Get married! Nervous your family might swoop down upon your possessions after your death? Make sure you get married! And so on. The implicit contract signed by the gay marriage movement has been this: We will keep our fucking up the ass in private, as long as you let us keep our property.2

All of this forms the penumbra around anal sex. It may not be foremost in people’s minds, but it is the history that bears upon us all, whether straight or gay, and it explains the ways in which this act like few others is such a metaphor for complete degradation and humiliation and why even its absence alone can create such legal furores. When it comes to anal sex, we are all ultimately taking it up the ass.

Footnotes:

1Anal sex has historically been defined within sodomy laws and thus tied to what are often referred to as “acts against nature,” which include oral sex, bestiality, and pedophilia.

The matter of lesbian sex plays a much smaller role in all this, since it has historically been less threatening.

2 I thank Matt Simonette for this important point, that, “for many gay men, the tendency to put anal sex ‘in the closet’ is not motivated so much by a desire for heteronormativity but a complete discursive panic over anal sex stoked by several years of bad sex ed and ham-fisted safe-sex messaging that’s taught us that our bodies are often nothing more than disease vectors.”

My thanks to all those who generously read, commented on, and discussed, at length, several different drafts of this piece: Ryan Conrad, Richard Hoffman Reinhardt, Gautham Reddy, and Matt Simonette. Any and all problems with the arguments here are mine alone.

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. I make a point of citing people and publications all the time: it’s not that hard to mention me in your work, and to refuse to do so and simply assimilate my work is plagiarism. You don’t have to agree with me to cite me properly; be an ethical grownup, and don’t make excuses for your plagiarism. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.