Excerpt: We no longer care to think about how to make the conditions of poverty (and hence the poor) disappear; we’d rather spend our resources freezing the culture of the poor in perpetuity.

Some of us might remember the short-lived ABC sitcom It’s All Relative, which came and went quickly in the spring of 2004. Its flimsy premise was the impending marriage of Bobby and Liz, who came from vastly different backgrounds and found themselves caught in the culture clash between their two sets of parents. The twist? Bobby’s parents were working-class folks from Boston, and Liz was the child of two gay men. The differences between the two families were drawn out in painfully obvious ways that highlighted class more than sexuality. Or, as the show’s promotional literature put it, “Liz’s parents are into St. Laurent. Bobby’s parents swear by St. Patrick. Bobby’s parents are devotees of the Red Sox. Liz’s parents are devotees of the arts.”

It’s All Relative suffered from insipid acting and dialogue; flat characters; and the writers’ inability to think beyond one season and a wedding—factors that doubtless led to its cancellation. Did ABC really expect people to tune in every week to watch yet another argument over whether to serve hot dogs or caviar at the wedding? But even as a blip over television’s landscape, it demonstrated that “gay” in the U.S. is thought of as a specific class identity, one that requires no explanation as to its origins and is considered inherently progressive. So, Bobby’s parents were Boston, Irish Catholic, Red Sox fans who were conservative in their politics. In contrast, Liz’s parents had no affiliations with any place or religion—they voted for Democrats because they were gay and that’s the gay thing to do. In other words, they came from nowhere and the only explanation required about their politics and class identity was their sexuality.

But if “gay” in America is now equal to being upper middle class or rich, it doesn’t follow that “straight” is equal to being poor. The opposition on It’s All Relative was not between gay and straight but between two class identities. Whether on such sitcoms or shows like Jeff Foxworthy’s Blue Collar TV, the poor/working class are increasingly the objects of the kind of derision that would not be tolerated if the narratives revolved around any recognized ethnic or sexual minority. Time Out Chicago recently profiled a theatre production by the ensemble Murder Mystery Players titled Bubba Ain’t Alone No More! The show features hillbilly stereotypes like a drunken reverend and an incestuous family, pulling in audience members to play the characters. The Kurt Russel movie Breakdown has the actor playing a man whose wife is kidnapped by a sadistic ring of redneck truck drivers. There are no reasons given for why these drivers engage in their criminal behaviour; we are led to believe that it’s just inherent to their cultural DNA as rednecks. Our cultural loathing for the lower class is so ingrained that we assume their behaviour is simply and entirely cultural. Hence a comment by one audience participant in Bubba Ain’t Alone No More, “this is just how crude people live.”

So the poor are the way they are because it’s their culture, just as gay men are fa-aa-bulous designers with an innate ability to choose the best wine and cheese and who automatically vote for liberal causes. My point here is that both “poor” and “rich” have become cultural identities in America, just like “Gay” and “African American” and “Asian.” We haven’t entirely accepted the poor as a suitable identity group, but if the recent surge in “Working Class Studies” in academia is any indication, they too will soon become objects of reverential analysis. We no longer care to think about how to make the conditions of poverty (and hence the poor) disappear; we’d rather spend our resources freezing the culture of the poor in perpetuity.

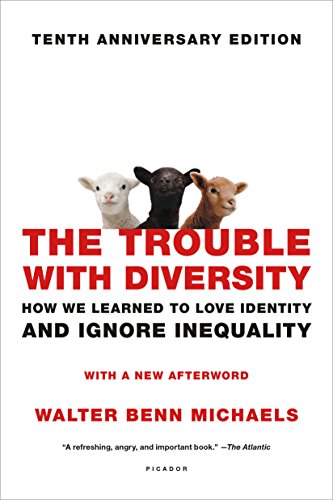

How did we come to a point where we fetishize disparate elements like sexuality, race and poverty as culture and ignore economic inequality? How do concepts like culture and identity, so wrapped up in the idea of attaining “full equality,” help in furthering inequality? Walter Benn Michaels persuasively provides a set of answers in his new book The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality. Michaels, a professor in the English Department at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), has been for many years a highly regarded and occasionally polarizing figure in academia. This is his first book aimed at a wider audience. Unlike most academics, he can unpack complex intellectual and cultural histories without resorting to jargon.

However, the real contribution of the book is its ability and willingness to take on the most revered principles of American cultural and political life: diversity, affirmative action, and a deep adherence to a respect for cultural difference. His argument about diversity is that it allows us to forget about economic inequality while increasing our reverence for difference. It’s to his credit that Michaels is able to write about weighty issues like race, culture, and inequality with wit, “We like diversity and we like programs such as affirmative action because they tell us that racism is the problem we need to solve and that solving it requires us just to give up our prejudices. (Solving the problem of economic inequality might require something more; it might require us to give up our money) .” A consideration of inequality may not seem like anything new, especially in the wake of Katrina when we found ourselves confronted with the images of very desperate and very poor people, mostly of color.

Kanye West’s declaration at a celebrity relief telethon that “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people” has become an argument in itself about the Bush administration’s supposed inattention to race. While the response is understandable, given what we saw, the issue of whether or not Bush is racist is beside the point (and this administration is the most diverse in history). Michaels’ analysis productively differentiates between race and inequality. The truth is that Bush—like the rest of us—doesn’t care about poor people. Or, as Michaels puts it, “We like blaming racism, but the truth is there weren’t too many rich Black people left behind when everybody who could get out of New Orleans did so … . This doesn’t mean, of course, that racism didn’t play a role in New Orleans. It just means that in a society without any racial discrimination, there would still have been poor people who couldn’t find their way out. Whereas in a society without poor people (even a racist society without poor people) , there wouldn’t have been.”

If anything, Katrina has led to a strange form of respect for at least some kinds of poor people, but that takes us nowhere to solving the problem of inequality. Michaels writes about an episode of Wife Swap where Jodi and Lynn, from rich and poor households respectively, exchange places. Jodi becomes aware of her prejudice against people who “live different lives” (meaning poor people like Lynn) —the lesson we are meant to take away is that the rich should not look down upon the poor. In other words, we are persuaded that being tolerant about what makes the poor different from the rich somehow solves the problems faced by the poor. That gets us away from the fact that the problem with poverty is poverty itself, not whether or not you are made to feel ashamed about it. It’s horrible to be poor. It means you can’t pay your bills, can’t fix your teeth, can’t put food on the table, and can barely make rent. But according to our cultural logic, hey, it’s okay to be poor as long as you are respected for being poor.

This is why it ultimately doesn’t matter if my opening paragraphs convinced you to respect hillbillies or not. Respect for poor people does nothing about the poverty in which they live and, as Michaels indicates in his analysis of the educational system, respect is one more way to keep the machinery of inequality going. Respect breeds band-aid solutions to the problems of inequality, prompting us to rely on a combination of charity and volunteerism to keep poverty in society temporarily at bay. We volunteer at soup kitchens and literacy centers and we depend on millionaires to keep foundations going. Whenever possible, we donate to education as if it were a cause, and not something that should be funded well and equally, regardless of where schools are located. We proudly teach respect and tolerance in our schools and ignore the fact that students often don’t get much of an education in anything else. We make a virtue out of the fact that inner city school teachers have to dig into their pockets to pay for basic supplies like chalk and textbooks for their students.

In other words, we’ve given up on the fight against inequality and have convinced ourselves that respect and tolerance for difference and identity will alleviate our problems. As for the gay movement, it has wholeheartedly announced its support for economic inequality in its fight for marriage. The dominant argument for extending the rights of marriage to queers has been that we should have the right to health care through our spouses, the same way that straights do. That ignores, of course, the fact that a large number of straight married couples don’t have health care because they can’t afford it. More damagingly, the gay marriage movement has no argument to make for universal health care, the single biggest signifier of inequality today. Instead of fighting so hard for the status quo, what if we replicated the actions of AIDS activists in the “80s who insisted that all of those with AIDS—Haitians, gay men, African-American women—were entitled to universal health care? So strident has our specious call for “equality” been that we’ve convinced straight allies to engage in some bizarre acts of solidarity. Charlize Theron, among other celebrities, has declared that she will only get married when gays have the right to marry. Well, first of all: Charlize, honey, stop using my people as a cover-up for not wanting to tie the knot with Stuart. But more importantly, how about a truly progressive act? Let’s imagine a world where gays are allowed to marry, and gain those much desired health care benefits. Will we then ever see gay couples refusing to marry and gain benefits until “everyone,” gay or straight, has access to universal health care?

Exactly.

The Trouble with Diversity kills a lot of our sacred cows and challenges us to formulate a truly progressive politics that focuses on poverty and economic difference. The trouble with diversity is the same as the trouble with equality, the buzzword of the gay movement. Both concepts replicate the status quo and neither takes us any closer to ending economic inequality.

Orginally published in Identity, January 2007