Ballantine Books; 320 pages.

The United States is a country of paradoxes when it comes to food. Obesity is an “epidemic,” but the number of hungry people has never been higher. In a 2006 Seattle Times article, Dr. César Chelala reported that 33 million people in the United States lived in households without an adequate supply of food. Since food is the most flexible part of living expenses, many are often forced to choose between it and essential payments like rent and health care.

The best response to this crisis is to advocate for a living wage and universal health care, but such solutions are thwarted by those who dismiss them as rabid leftist propaganda. Our way of feeding the hungry is to do so inadequately and with immense doses of humiliation by setting up soup kitchens and food pantries that donate food.

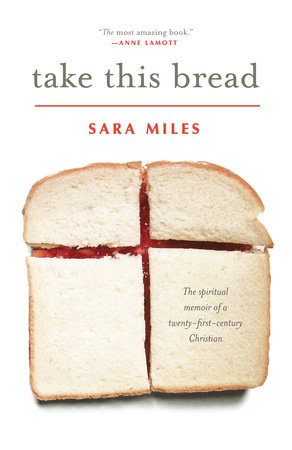

Sara Miles is a former leftist journalist and professional cook who happens to be a lesbian. In her new book, Take This Bread: A Radical Conversion, Miles recounts how she went from being an atheistic social justice activist to the founder and director of a food pantry at her San Francisco church, St. Gregory’s. The book starts out as an engaging take on food and life, with some funny bits about Miles’s experiences in restaurants.

As her journey progresses, however, Miles remains a lesbian while her leftist politics disappear. People have a right to their faith, but Take This Bread exposes thorny issues about the role of religion in social justice. Miles works hard to convince someone—perhaps herself—that her new-found conversion and, well, missionary zeal is really part of a larger “radical” social justice mission. Miles can’t see the pity for the piety and mistakes charity for social justice.

Charity does not bring about revolutionary social change. She’s proud of the fact that St. Gregory’s, unlike federal programs, does not ask for identification, which means that undocumented migrants can avail themselves of this resource. She’s also proud that her program emphasizes fresh produce and healthy food, rather than dumping cheap junk food on its clientele. But while serving better food to more diverse bodies may alleviate hunger, it doesn’t eradicate the systemic conditions that lead to poverty in the first place—and even extenuates them.

Take, for instance, the San Francisco Food Bank (SFFB) where St. Gregory’s gets its supplies. We see the tip of the iceberg when its executive director tells Miles, “We’re simply a part of the market.”

And how. SFFB gets food from the giant corporations, called agribusiness, that have taken the place of independent farmers across the country. In exchange for its donations to food banks, agribusiness gets tax write-offs. That makes it more profitable. That makes it harder for workers, especially migrants, to unionize or demand fair wages. That creates more poverty and more underpaid laborers, who line up at food pantries like St. Gregory’s. Which work with enterprises like SFFB, which work with agribusiness. Leaving agribusiness free to continue bad labor practices.

Be scared. Be very, very scared.

Ultimately, this is an immensely useful and revealing book, if not in the ways Miles intended. Her account of giving free food to poor people tells us nothing about how to end the systemic conditions that produce such depths of poverty in the richest country in the world. But it reveals how Charity, practically a religion unto itself, is as much big business as an instrument of liberal good will.

For more, see also my “Food Pantry Shortages: What’s the Real Story?”