Skloot’s remarkable book parallels a deeply important story about a scientific breakthrough with an equally riveting one about the human subjects whose active and inactive participation helped make it possible.

Crown Press; 369 pages, 2010

In 1990, the Havasupai tribe of the Grand Canyon gave DNA samples to Dr. Therese Markow, an Arizona State University geneticist, hoping for genetic clues about their high rate of diabetes. Markow found none but the DNA continued to be analyzed by various researchers who found that the Havasupai originated in Asia, contradicting tribal mythology that they sprang out of the Canyon.

The Havasupai were outraged, fearing that the revelation might threaten their claim to sovereignty over the land. They also felt that their DNA had been researched in an unauthorized fashion. They sued and, this April, ASU agreed to pay “$700,000 to 41 of the tribe’s members, return the blood samples and provide other forms of assistance to the impoverished Havasupai,” according to The New York Times. The settlement may be the first of its kind. DNA samples have traditionally, usually, been taken without explicit content, but there is a growing backlash from patients.

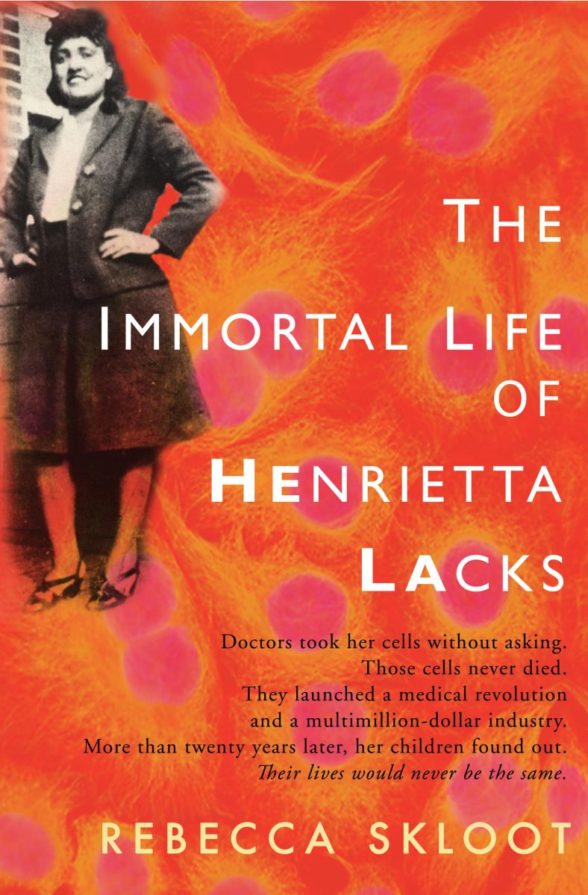

No cluster of cells is more famous than that of Henrietta Lacks, an African American woman who died of cervical cancer in 1951 in Virginia, only eight months after her diagnosis. Collectively known as HeLa, Lacks’ cells are at the center of the engrossing new book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, by Rebecca Skloot. The cells were scraped from her cervix without her informed consent. Unlike average cells which die after a few hours of study, HeLa cells survived long after and kept multiplying. By now, they have been instrumental in some of the most significant medical research and discoveries, including the polio vaccine.

Henrietta Lacks was born in 1920. Johns Hopkins, where she was treated, was the only hospital in her area that would admit Black patients; she was seen in a “colored-only” exam room. At the time, the hospital had no qualms about exploiting Black patients. Howard Jones, the gynecologist who examined Lacks, wrote, “Hopkins, with its large indigent black [sic] population, had no dearth of clinical material.”

Over the years, HeLa cells have made billions in profits for various biomedical companies while the majority of the Lacks family does not have health insurance. Such ironies reveal the frequent poverty or disempowerment of subjects used in research and the history of a medical industry which has a long and racist history of exploiting people of color, as in the infamous Tuskegee Experiment. It might be technically difficult to assert or prove that Lacks’ descendants ought to have a share in the profits. Indeed, as Skloot points out in a very comprehensive final chapter which examines the ethics of such research, medical science might suffer if the extraction of cells from patients’ bodies is overly regulated. Yet, Lacks lived in segregationist America, and poor people of color are still routinely denied equal access to the best medical care – either through outright and racist (if covertly so) denial of the same, a broken health care system that excludes the poor, or a combination of the two factors. We have to confront the vexing contradictions that arise out of such circumstances, and Skloot does not shy away from them. Queers have an interest in knowing about such moments given the history of our desires and bodies being scrutinized, medicalized and incarcerated against our will – practices which are still prevalent in the U.S and abroad, under the guise of “reparative therapy,” for instance.

Race and economic inequality are central here. Skloot is conscious of the race and power dynamics in which she is implicated, but it is still worth noting that Lacks’ story is now garnering great attention in mainstream media only after a white writer brought it to the forefront. The Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta has hosted conferences in honor of Lacks since 1996 – and those have gone largely unnoticed by mainstream media.

Skloot’s remarkable book parallels a deeply important story about a scientific breakthrough with an equally riveting one about the human subjects whose active and inactive participation helped make it possible. We learn about the dedication of George and Margaret Gey, the husband-and-wife research team whose tireless quest for immortal cells made the discovery of HeLa possible. We also learn about Lacks. Among the sadder elements of her brief life is the haunting story of a beloved daughter Elsie who was institutionalized as a child with “idiocy.” She died at fifteen, never knowing that her mother had died, and with no visits from anyone else after Lacks’ death. Henrietta Lacks was buried in an unmarked grave; it only received a headstone in May of this year.

There are still vexing questions around disclosure and profits, and the case of the Havasupai raises more. While they may have a right to know how their DNA was studied, should they be outraged at the revelations? After all, they looked to science for answers. One unintended consequence was an unwelcome but scientific account of their tribe. When it comes to what secrets are unlocked by our cells, are we afraid of what we are not told or what we might be compelled to find out?

Originally published in The Windy City Times, August 4, 2010