“My mother and I pretended allegiance to their Tupperware parties, to their Brownie troops, to their Sunday morning services at the Presbyterian Church.”

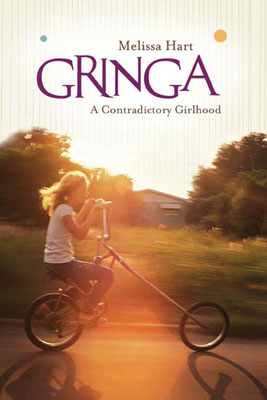

Seal Press; 276 pages

Memoirs about growing up and feeling out of place are usually about people struggling to become part of the dominant culture. Inevitably, these are also tales about food, and much of the drama comes from the olfactory and textural differences between cuisines. Linda Furiya’s Bento Box in the Heartland: My Japanese Girlhood in Whitebread America is one example, as is Stealing Buddha’s Dinner by Bich Minh Nguyen, an account of growing up Vietnamese in Michigan. The emphasis on food as a central trope in immigration is not unusual given that the “melting pot” is part of the mythology of the United States.

Melissa Hart’s Gringa: A Contradictory Childhood also centers on food as a way to enter into a culture, but her memoir is unusual in that it involves a young and very white girl who is transplanted from a Los Angeles suburb into the predominantly Mexican-American farming community of Oxnard. Hart’s whiteness is not only marked by the paleness of her skin, frequently commented upon by her Mexican-American friends, but by the “American” food and rituals with which she grew up. During Hart’s third grade, her adventurous mother had grown weary of the confines of suburbia, and the two became partners in crime as they learned Spanish together, aspiring to a life outside their borders: “My mother and I pretended allegiance to their Tupperware parties, to their Brownie troops, to their Sunday morning services at the Presbyterian Church.”

It turned out that there was more than the love of a language involved in this endeavour, as Hart’s mother eventually decamped with Patricia Sanchez, the school bus driver. But this was the late 1970s, and lesbian mothers, seen as immoral and damaging influences, were not likely to get custody. According to her Web site, Hart’s custody story is part of the 2006 documentary, Mom’s Apple Pie: The Heart of the Lesbian Mothers’ Custody Movement. But Gringa is less about the custody battle and more about Hart’s own coming to terms with her whiteness and her sexuality, and her account of that makes for a gently engrossing tale that carefully unwraps the multitude of contradictions in which she finds herself.

As Hart grows up, she wants nothing more than to be like her friends in Oxnard, and she also wants nothing more than to be just like her beloved lesbian mother. Hart fails miserably at both. No matter how hard she tries, she is always literally the one white spot. She manages to secure an invitation to the quinceañera of a friend of her friend Rose, and finds herself relegated to the role of photographer instead of dancing with wild abandon as she had hoped. When the photos are finally developed, she sees herself as the outsider she is fated to be: “If you looked closely, you could see it poorly placed in the second row to the left … a white blob going nowhere.”

Hart’s attempts to fit into Mexican-American culture could be seen as problematic, and they are. What saves this book from becoming a cringe-inducing and fetishistic account of a white girl trying to appropriate “foreign” culture is the fact that Hart is unafraid to make it clear that she was, more often than not, making an ass of herself and, worse, that her attempts to assimilate were often insulting. Having acquired a Mexican boyfriend, Tony, she shows up at his family holiday party dressed as a Christmas tree, complete with brown paint on her face, hoping to raise some levity. She listens uncomfortably as someone tells her, “the family thinks you are making fun of their party.”

At a dinner party for her father’s boss, she meets the sophisticated 14-year-old Natalia, who has the added allure of an elegant Spanish mother, and the grade-school age Hart instantly resolves that this will be her girlfriend. Natalia’s main interest in Hart is to inveigle her into sneaking the crème de menthe from her father’s liquor cabinet, and Hart is anxious with hope: “Would the touch of Natalia’s hands seduce me…? I tried unsuccessfully to break into goose bumps.” Eventually, by the end of the evening, left cold without desire, she reluctantly reconciles herself to the fact that she is no lesbian.

Gringa takes us through Hart’s adolescence and her college years, ending with a long-awaited short trip to Spain with her mother. Determined to be “authentic,” Hart tucks Rick Steve’s Europe through the Back Door into her backpack so that they might “avoid tourist traps and experience the real country and its people.” When they arrive, every tourist in Spain can be seen walking around with in the book. Eventually, the two women give up on Hart’s plan of authenticity and, following her mother’s meanderings, actually enjoy the trip. At the end, Hart contemplates her attempt to become a “citizen of the world,” her dictatorial tendencies on the trip and a bust of Franco, to which she whispers, “Dude, you need to lighten up.”