This year’s May Day celebration came at a time of both hope and uncertainty for both LGBTQ and straight attendees. With an Obama administration in the White House, there is hope for substantive changes in policy among labor organizers and immigration activists. But this year’s rally came in the midst of an outbreak of “swine flu,” later dubbed A(H1N1) by the World Health Organization. Since this particular strain is reported to have its origins in Mexico, and because Chicago’s annual May Day march has effectively become an immigrant-rights march, concerns about contagion caused initial uncertainty about whether or not the event would even go on.

City officials initially tried to get organizers to cancel the march. Jorje Mujica, of the March 10 Movement—a group that was key in organizing the march—said, “the flu is being wrongly cast as a Mexican disease. The city wanted us to cancel the event, but we refused. They didn’t issue those orders for the Bulls game. This is not about influenza, but about political influence.”

Gina Parker, a member of the Dyke March committee, was among the LGBTQ people who made their presence known, along with members of Gay Liberation Network who stood near large rainbow flags at the southwest corner of Union Park. Parker said she was there to “show solidarity with the immigrant community. Dyke March is going to be in Pilsen again this year, and it’s important to show the dominant culture that there are queer people among and with immigrants.” While there were many LGBTQ-identified participants in the march and several rainbow flags, there was no monolithic “queer agenda.” Instead, individuals and groups participated with distinctive but connected issues in mind.

Kevin Brown of Gender JUST (Justice United for Societal Transformation) was among the group’s members collecting signatures for a letter to Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) Commissioner Terry Mason to make the CDPH HIV funding process more transparent. He said that the group wants to highlight the need for more prevention strategies to be made accessible in more than a few organizations on the North Side: “Right now, LGBTQ youth on the south and southwest sides of the city have to commute to the North Side for resources, and they should be able to access them in their own neighborhoods.”

The issue of immigration touched many people personally. A group of queer-identified Social Justice High School students walked around with flags. Among them, freshman Yahtzeni Gonzalez said they were marching “for all of us. A lot of our friends struggle as immigrants, and many have had their parents deported back to Mexico, which leaves our friends homeless and without the support of their families.”

For many attendees, being at the march meant wearing multiple hats that reflected their lives at the intersection of LGBTQ and immigrant issues. Tania Unzueta was attending as a member of the Dyke March Committee, but she was also there as the director of Radio Arte’s youth training program and producer of Homofrecuencia, a weekly student-produced radio show. As her students bustled about interviewing people and Tweeting updates about the march, Unzueta spoke about the tangible ways in which their lives are affected by immigration policies. One student, Rigo Padilla, who is taking a course at Radio Arte, was brought to the United States as a 6-year-old by his undocumented parents. He was recently picked up on a DUI charge and saw the charges escalate into a deportation case; he is scheduled for a deportation hearing and faces voluntary departure to Mexico even though he has lived in the United States all his life. Padilla was wearing a court-mandated ankle bracelet while reporting. Unzueta said that his case pointed to the unfairness of laws, and questioned whether Chicago could be considered a sanctuary city given his case, “If you are a citizen and stopped for a DUI, you don’t face something like deportation. His DUI should have nothing to do with his immigration status.” 17-year-old Hester Rivera, also an undocumented student at Homofrecuencia, said that he was there to “connect with students without papers. Getting a job is really hard with my status. I’m hoping to get legalization and become a dancer, and keep participating in this movement.”

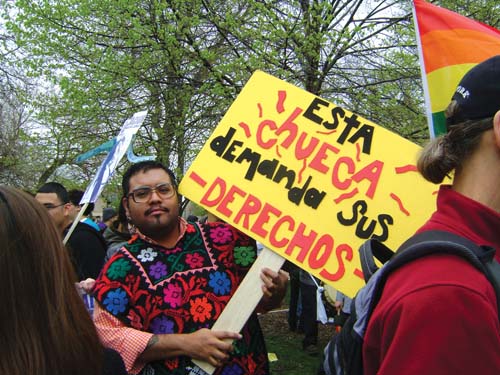

The issue of solidarity was a common theme for LGBTQ people. Tony Alvarado-Rivera of Howard Brown Health Center’s Broadway Youth Center said, “I’m here as a Chicano/a and as a queer, because I recognize my privilege as a citizen. I feel we are multi-issue people—queers are immigrants and workers, too. Besides, it’s fun to be sassy in a non-queer context.” His handmade sign demonstrated his philosophy. In Spanish, the words were, “Esta chueca demanda sus derechos.” Loosely translated as “this crooked one demands its rights,” it was also a play on words, with ‘derechos” meaning “go straight” as well as “rights.”

Several members of Bash Back! were also present, and the queer anarchist group enlivened the march with its energetic dancing. Member Maggie Block said the group was there to focus attention on immigration in its larger economic context: “As anarchists, we’re opposed to borders and states. But the mainstream has to think about how the United States created a situation—with NAFTA and free trade—where the agricultural industry would collapse without the use of exploited labor. Yet, we raid and deport the very people who make our cheap prices possible. We have to end these schizophrenic policies.” Imi Rashid of Akabaka Bangali, a queer Muslim group, said that she felt the march was “a culmination of all disenfranchised folks; undocumented people need to be treated fairly.” She said that most people aren’t aware that immigration can be onerous even for documented people, “I’ve been through the process and it sucks. It took me seven years to get my green card, and I came up as a documented person.”

The march, dotted with colorful signs and giant puppets, made its way from Union Park to Federal Plaza.