Excerpt: If “queer” means anything, and if we queers have given anything to the world, it’s a combination of sex and love that stretches the imagination and the concept of friendship.

It takes fifteen minutes for Jason Momoa to make an appearance in Aquaman, the longest fifteen minutes in cinematic history. When he finally shows up, it’s in this scene, where he jumps into a submarine and, with a turn and toss of his hair, sarcastically asks for “permission to come on board.” At one movie theatre, his first entrance on screen prompted a viewer to let out a gasp and cross her legs. That Momoa is deeply attractive is to put it in the blandest possible terms. If space aliens came to earth and demanded to be shown that we had achieved anything like perfection after centuries of existence, Jason Momoa would serve as proof. Even a hardened cultural critic, a scholar of film and television history with a keen and cold awareness of the entirely constructed nature of Hollywood, stardom, and celebrity might yet melt at the sight of Momoa, whose tousled mane, numerous tattoos, and always bare, muscled arms are proof of something she cannot name because she is utterly distracted. And, based on informal research, it’s fair to say that Momoa makes several straight men question their sexual orientation and hover their pens above the box marked “Questioning.”

Momoa is integral to the success of Aquaman. That may seem like an obvious point—he is, after all, the actor who plays the title character. But it’s not just that Momoa plays Aquaman: the comic book hero was completely reconceived for the film and in his likeness. A DC character created in 1941, Aquaman was (and still is, in the comics) blonde and white, and while his story has a complex trajectory spanning several decades (it includes fighting Nazis), he has been the target of several jokes about his powers, most of which involved communicating with sea animals, not the most useful to have on land. The 2016 film Batman v Superman introduced a new version of the hero, this time entirely derived from the look of Momoa himself, including the actor’s own shark tattoo, his hair, and his ethnic heritage (his mother is Irish-German-Native American, and his father is native Hawaiian); Momoa frequently refers to himself as brown and as a person of colour.

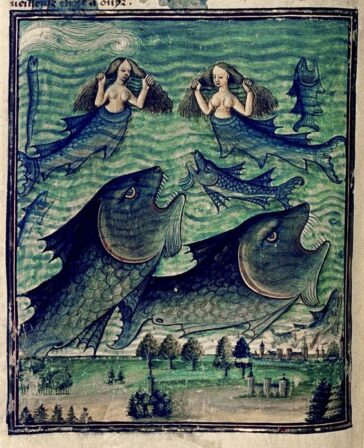

Which is to say: Aquaman went from this, to this, and now looks like this.

Most comic book heroes have changed over the years: their bodies have gone from being vaguely naturalistic (and mostly human-like, just with capes and tights) to powerfully (and powerfully unreal) ripped muscles and six-packs, the likes of which are only attainable by people who spend every day in the gym and probably consume massive amounts of steroids. Superheroes used to be more, um, “faggy,” as a queer friend puts it—not for nothing did the Adam West version of Batman cavorting with Robin become a queer icon. The Ambiguously Gay Duo, the animated sketch show, plays up the historical queerness of superheroes, with bulging tights and raunchy dialogue. Today, superheroes are generally hyper-muscled and very straight. But the racial change in Aquaman is a fairly dramatic one, as is the rocker persona; it’s fair to say that Aquaman today, as seen in the film (and, given its enormous success, now permanently enshrined as the Aquaman, for many), is in fact also Momoa. To be clear: it’s not as if Aquaman/Arthur Curry has been completely de-whitened, but the film extracts a racial ambiguity from him: the very white Nicole Kidman plays his mother but his father is played by the part-Maori Temuera Derek Morrison (reportedly on Momoa’s insistence). Even in this, the film runs parallel to Momoa’s own family origins.

Given all that, Jason Momoa’s celebrity is now spliced into the DNA of a comic book hero recast in his mould. But it’s not just superheroes and comic books that have changed over the years: Hollywood itself has undergone drastic changes, as have its underpinnings of publicity and the relationships between those we used to call stars and those who consume their images, once easily differentiated as “the public” (now that celebrity is potentially available to all, the lines have blurred much more).

There was a time in Hollywood when film stars were tightly managed by the studios to whom their entire lives and wardrobes were tied, and that kind of control was enabled by a vastly different world of media where a few journalists and magazines controlled the news about stars—and could, on occasion, themselves be controlled with judicious bribes that included carefully portioned out scoops and interviews. Rock Hudson was, by several accounts, famously and carelessly (in the eyes of fuming studio executives) out as gay, as much as you could be such at the time, but a quick arranged marriage to his agent’s assistant bearded him and let him wander around untethered, kept safe by a public illusion of heterosexuality. Today, stars are celebrities and while getting a major movie deal is still, for many, the pinnacle of success, the attainment of celebrity requires massive amounts of public performance that are in turn tied to endless commercial enterprises that need constant tending. Gone are the days when you could be known for being known—which is to say, gone are the days when even Angelina Jolie, not that long ago, existed as a celebrity without a Twitter handle and a Facebook page. Today, anyone who wants to achieve that level of fame has to be embedded in a set of social network interminglings. And even then, most film actors don’t have the draw and earning potential of say, Kendall Jenner, who reportedly made $250,000 for a single Instagram post promoting the disastrous Fyre Festival. Jenner has 102.9 million Instagram followers; Jason Momoa, who has been acting for nearly twenty years, most famously as Khal Drogo in Game of Thrones, has 9.5 million. Jenner’s IG profile isn’t just a string of pretty pictures but a wave of paid endorsements; Momoa also features ads for sponsors like Carhartt apparel, filmed with the look of dreamy home family videos, lending to his image as both a family man and boho bikerdude bro.

Which is to say: Jason Momoa’s seeming newness emerges from the very same Hollywood construction of public personae that might have forced a gay actor to marry or a female actor to get a nose at studio expense. Actors today are independent contractors, but the constraints on them and the subtle and not-so-subtle ways in which they shape their public personalities are no less intentional or calculated. What’s different is the sense of immediacy that allows followers on Instagram or Twitter to gain a sense that they actually know a celebrity. There are clear drawbacks to the transition from stardom to celebrity: where a studio could swoop in to save the day on the occasion of a barroom brawl or a back alley blowjob that needed to be kept out of public view, today a single misstep on Twitter could mean a highly public end of a career.

Instagram, like YouTube, is a particularly complicated enterprise because its strong visual focus lends to advertising—witness, any of the Kardashians. In recent years, there have been demands that celebrities and “influencers” in fashion and style should reveal their commercial ties to the manufacturers whose products they promote, but this is unlikely to become a widespread practice because the blurred line between advertising and spectacle is what consumers of Instagram voraciously devour: everyone knows there are commercial interests afoot, but what matters most is the quality of the images being traded, quality that often surpasses what print or internet campaigns might offer (anything considered sub-par and unsophisticated is either instantly mocked or disappears quickly). What Instagram also does, in ways often mocked and memed, is allow people to create images of their lives that are often supremely unreal and illusory. In the movie Ingrid Goes West, a woman follows her favourite Instagram influencer to California, with disastrous and semi-comic consequences, in the process unraveling an entire set of lies and make-believe worlds. In effect, Instagram celebrity isn’t about proving the reality of the life you claim to lead, but demonstrating that the construction of your celebrity is as finely put together as possible.

Momoa’s own portrayals of his life and his consumption patterns, as seen on Instagram, are in line with the persona he cultivates with his fashion choices (a persona that may well match him in real life), greatly enabled by the fact that they involve his wife Lisa Bonet, their two young children, her ex-husband Lenny Kravitz, his stepdaughter Zoe Kravitz, and a host of friends and family he appears to have been with and around for much of his life. As is clear from that list of names, he’s surrounded by a particular kind of glamour, not the conventionally understood style of designer suits and Van Cleef & Arpels, but high glamour nonetheless, one that still boasts designer names and expensive, artisanal craftsmanship, with a whiff of boho-hippy chic (the very essence of Steampunk, an expensive style to maintain).

Even though Khal Drogo was killed off in Season One of GOT, the character remains massively popular (with several fans wistfully hoping that the show’s mystical elements might mean his eventual rebirth and return in the upcoming and final season). Momoa’s Instagram account consequently involves several of his castmates from the show who have gone on to their own stratospheric heights of celebrity, including Emilia Clarke, who plays Daenerys Targaryen; his feed includes several images of him “hanging out” with them (even if, like nearly every character in the show, bar a few, they were also eventually killed off—the show is rough on human and animal lives).

Momoa’s life as seen through these prisms is no less a construction than that of any of the Kardashians, it’s just a different kind of life. Where Kendall Jenner’s life looks like she spends all day in one slinky outfit after another, attending premieres and galas wearing and sporting several sponsored items on her body (she is literally a walking billboard), Momoa’s persona is that of a wanderer making his way through the world and running into interesting people in interesting places. Like the more sophisticated IG users, he’s able to combine a knowingness about the commercial nature of his posts with a sincere sense of living in the moment. Sure, he shows up at Guinness headquarters in Dublin and, sure, it’s bound to be a mutually beneficial relationship (at the very least, we hope, a lifetime’s supply of the beer), but Momoa has also been an avowed fan of Guinness long before he reached mega-celebrity proportions of visibility; it’s hard to not see his genuine sense of pleasure of being somewhere or with someone he likes and admires.

Which is to say, and to put it simply: It’s hard to not smile at Momoa’s clear enthusiasm and infectious zest even as we, even the hardened cultural critics among us, narrow our eyes and see the constructed nature of his online and public personality. It’s hard to not laugh alongside him as he cheerfully romps around the set of Saturday Night Live for promos for his December 8 appearance in nothing but a towel, screaming his delight at finally having achieved a lifelong dream of appearing on the show. His skits that night were, let us admit, hilarious, even in the somewhat off-kilter and awkward one where he played Khal Drogo. The best of the lot involved him dressed as what can only be described as a slightly gay Stripper Santa who shows up at the house of Ebenezer Scrooge—but after Scrooge has achieved his famous clarity on the meaning of life and been visited by all the Ghosts of Christmas—and claiming to be a little “extra” ghost. Scrooge, unable to see the point of Santa’s provocative first dance, fully clothed in an ermine and red robe, asks, “What lesson did I gain from that?” To which Momoa responds, with deliciously over-the-top pique, “Seriously? You should be like, ‘Boy, why’re you so extra?’”

The SNL skit is only one example of Momoa being willing to (temporarily) forego his claims to a very public masculinity that has been the basis of his career, to hilarious effect. He has, in several interviews shown up with his hair in pigtails and pink scrunchies (and shows a fondness for pink in general). None of this is in itself groundbreaking and revelatory: if being seen as gay or gayish was poison to straight actors’ careers even a decade ago, being able to play gay is practically a career requirement these days. In that sense, Momoa is not dismantling patriarchy and masculinity as much as he is moving along with newer cultural paradigms: the best way to reinforce masculinity now is to step out of it, judiciously, every now and then.

And yet.

As with his infectiousness, it’s hard not to appreciate Momoa’s playing with gender and sexuality, given the warmth and verve he demonstrates (he may well be acting and in which case, we might at least appreciate his brilliance at the job). To return to his Instagram feed and general public portrayal of his life and loves: it’s hard not to take seriously— or at least deeply appreciate—an important facet of his posts and interviews: the emphasis on friendship, one that cuts across and blurs conventional lines of gender and sexuality.

In an interview with Graham Norton, Momoa is asked about his friendship with Emilia Clarke, now the star of Game of Thrones. The two famously played romantic partners in the first season of the show and have remained, at least in public, fast friends since then, attending premieres together and often being photographed in apparently unfiltered and genuinely joyous embraces. Norton asked if fans might not go crazy over the photos of the two of them, taken a week before, and he responded, “I go crazy when I see her.” Their IG feeds are strewn with lovelorn notes to each other, using the terms their characters used in the show. Similarly, Momoa frequently posts about other friends, much less known to the public, including long-time trainers and actors and athletes he has known for years, as well as his large and extended family that stretches from Iowa to Hawaii. The overall effect is of a tribe of people, brought together in ties that are both tangible and intangible, visible and yet also part of a deeper, longer set of connections that bridge and overlap with each other.

Again, none of this is unusual—K.J. Apa and Cole Sprouse have a well-known bromance which even involves them vacationing together in New Zealand—and seen within the demonstrably public and crafted contexts of Instagram, we might, again, narrow our eyes and consider how all of this is carefully wrought as an exercise in public relations. In many ways, Momoa and his celebrity are reflections of a millennial world, where relationships are less defined by marriage and more by structures of feeling. But we might, momentarily at least, revel in what we see, celebrate the fact that in 2019 it’s not just okay for a 6 foot 5 tall model of masculinity to play gay and wear pink but to voraciously and delightedly take pleasure in an intense friendship with a woman he’s not married to, to speak about his tribe of friends without constantly, as has been the cultural habit of yore, defining and laying boundaries around what are and are not acceptable relationships.

The (only slightly satirical) song “Magic Boy,” in Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt’s Season 4, episode 7 is a riff on the theme song of the 90s sitcom Living Single, and has a line, “It’s a 90s kind of world, and everyone is gay.” And it’s true: the 90s was the decade where everyone came out, and television shows in particular exploded with gay characters or sitcom stars telling us how gay they were. But the twenty-first century seems to be queer rather than gay: if the 90s were about establishing that homosexual relations are okay, our times now seem to be expanding the idea that relations of all sorts are okay. In that light, without reductively “queering” the film (a tiresome 90s queer theory exercise which needs to die), we might consider that even Aquaman, with Jason Momoa front and center in it, barely elaborates on the conventional heterosexual relationship that is often integral to superhero mythology.

In the film, Amber Heard’s Mera is a princess (and laden with Gatorade-red locks as if to prove her status) but also an adventurer and political strategist in her own right who has to keep rescuing Momoa’s Arthur Curry from one seemingly intractable tight spot after another. Unusually for a film about a superhero, ours is fine with deferring to Mera’s experience and follows her lead. As might be expected, the relationship develops and there is A Kiss but it’s perfunctory at best, and the two continue in their mostly separate ways. Vengeance, greed, power, family debts, political unification: all of these are the driving forces of the story, but the romance is tertiary at best (it does at least bring us Roy Orbison’s hauntingly beautiful “She’s a Mystery to Me”). At the end, as they stand together and contemplate his future as King, he kisses her but it’s a brotherly kiss, planted hard on her head, and his arm around her indicates she’s less a consort than a buddy: “This is going to be fun!”

As a movie, Aquaman is as big a hit as it is because of its truly spectacular special effects: its story and dialogue are not the greatest and Momoa’s talents are surprisingly underutilised, with him mostly reacting to people. The camera lavishes attention on his body and face— something generally done to women, and a fact for which countless viewers across genders and sexualities are grateful. It’s a film spanning several underwater mythologies (earth’s petty problems are secondary, except as the anger-inducing source of the pollution that threatens the oceans), and not all reviewers seem to have grasped a fundamental fact: that it’s pure fantasy. One complained about the physics of the underwater world: “How do some things float and others lethally — loudly — hurtle to the sea floor?” But this is a film where a hero comes riding in on a sea horse (okay, fine, sea dragon) and a giant octopus plays tribal drums (magnificently): why not simply suspend disbelief and enjoy the ride?

The financial success of the movie, which has already made over $1 billion, guarantees at least a sequel, possibly many more. It may well be that the next one chooses to focus on conventional themes of family (in the comics, Mera and Curry have a child), and we are thrust into some boring version of an underwater hetero romance. We can only hope that Momoa is finally allowed to let his comic flair shine forth, and that the octopus is given a bigger role; crafting a riveting story while bringing in even more spectacular effects, necessary if the audience for the first one is to return, is going to be a tricky task (the Aquaman crew could learn a lot from the brilliantly written and hilarious Thor Ragnarok).

But for now at least, we can hold on to the promises held forth by the reworking of a 1940s white, blonde hero into a seemingly and mysteriously bi-racial bikerdude bro who doesn’t have a problem with a woman telling him what to do. We can hold on to the pleasures afforded by the fact that said hero is played by an actor whose public life and images are underpinned by a retooled publicity machine but also clearly formed in a post-heteronormative world that revels in complicated relationships that were once the domain of “queer.” There’s some irony in the fact that gay celebrity couples like, Ellen De Generes and Portia de Rossi are now, if you will, coupled to the idea of the presenting themselves as, well, coupled. Tig Notaro, every straight person’s favourite lesbian, is resolutely suburban in her portrayal of lesbian life. Much of this may have to do with the fact that gay and lesbian actors aren’t yet working in an environment where they can be more than conventionally, acceptably gay and lesbian and have to take up the burden of proving, in the wake of gay marriage, that they’re fit to be seen as “normal.” They’ve only just been allowed to be seen in relationships and if those should prove to be…complicated, they’re likely to suffer a backlash (and perhaps receive a behind-the-scenes admonition from organisations like the Gay and Lesbian Alliance against Defamation, which monitors gay and lesbian representation to a sometimes absurd degree). Any straying from the idea of a relationship that is not about love and commitment and centres the couple, and all of homosexuality, it is implied, will explode and vanish from the earth. But hetero couples take on, increasingly, the mantle of queerness, of exploring and keeping relationships that are more flexible: Lenny Kravitz shows up to support Momoa on his SNL night, and Kravitz and Lisa Bonet attend premieres together while Momoa and Clarke drunkenly reenact that scene from Dirty Dancing and talk of loving each other.

If “queer” means anything, and if we queers have given anything to the world, it’s a combination of sex and love that stretches the imagination and the concept of friendship. Conventional heterosexuality has been bounded by a need to define friendship between non-romantically-linked opposite-sex people as nothing but a field of landmines, sending therapists and columnists into near-panic. Queers, perhaps because unencumbered by notions of how gender ought to work and because our survival has depended on keeping our tribes together, have been historically flexible on that count: Amy Hoffman titled her memoir about journalism and the AIDS years An Army of Ex-Lovers. Attend any queer gathering, and you’re inevitably surrounded by such armies and trying to disentangle the complicated and usually long-term connections between exes, various progeny, cats and other animals and current lovers would be a fruitless task. We queers ask, on some level: whom do you love in ways that exceed bounds of conventional romance, and whom might you sleep with and then bound back with into a long and abiding friendship without feeling the need to “break up?” Nothing is perfect and this is by no means the last word on the matter, but we can safely say that queers have perfected the art of friendship as something not defined by whom you are or are not sleeping with but who excites you and whom you keep in your ambit: Who makes you crazy with love when you see them?

Perhaps the web of friendships we see in Momoa’s public life and the lives of those like him are simply part of a millennial publicity machine, one that carefully sees and absorbs lessons from the zeitgeist and massages its messages accordingly, like infusing an expensive vodka with the essence of a rare Himalayan plant. Perhaps none of this is true and everyone secretly hates each other.

Or we could, as critics must and should in evaluating Aquaman’s basic premise, willingly engage in a suspension of disbelief regarding how love is supposed to work and immerse ourselves in the multitude of possibilities offered by the overlapping images and stories surrounding Momoa and his tribe, and the sly and insidious ways in which all that penetrates the reworking of Aquaman, the hero and the movie. Maybe, just maybe, a sequel will involve a tribe of friends, some of whom may have slept with each other and tended to each others’ cats and borne each others’ babies. Perhaps, having banded together to defeat a giant oil corporation, all of them will eventually dance to the beat of a giant drumming octopus and a different way of inhabiting relationships.

Many thanks to Ryan Conrad, Gautham Reddy, Richard Hoffman Reinhardt, Kate Sosin, and Matt Simonette. Everything worthwhile in this piece is due to them, any problems are mine alone.

See also “Friendship in the Time of Love.”