Suddenly, trafficking is in the news. And it’s sexy. NBC’s Law and Order: Special Victims Unit has dramatised the issue twice this last year. In one episode, a predatory Russian trafficker entices a barely pubescent American girl with e-mails so alluring that she runs away to join him. Once in Russia, she begins a tangled relationship with her captor and her body is sold as she falls into a drug-induced stupor. She is, of course, eventually rescued by NYPD’s finest but not before viewers get glimpses at the explicit web photos used to advertise her services. Another episode is about children imported from Africa as part of an elaborate trafficking enterprise. Things go awry when one young boy dies from what looks like a ritual hanging. The detectives find that an art professor who killed the boy, fearing that his wife might discover his paedophilia, rented the child for sex.

Most of us think about trafficking in these terms, as a phenomenon that locks women and children into sinister sexual relations with unscrupulous foreign men; we also think of it as something that happens outside our national boundaries. The trafficking of human beings as unpaid labour is in fact widespread within the United States. According to the Department of Justice, approximately 700,000 persons are trafficked worldwide and about 50,000 them are trafficked into the United States (see map). According to a 2003 Department of Health and Human Sciences survey, 54% of those trafficked into the U.S. are male, 46% female and only 4% are minors. Some may enter the country on work visas but soon find themselves at the mercy of traffickers who take away their passports and legal documents, leaving them in a strange country and unable to speak to anyone outside workplaces which include farms and sweatshops.

Actual numbers are admittedly hard to pin down because trafficking’s success depends upon its tightly-knit networks and its ability to deliver labourers who will not reveal themselves for fear of retribution from their captors. Depending on the sources, the numbers are either higher or lower than those above. Regardless of where you look, it’s clear that human trafficking is a serious problem. In terms of gender and the question of forced sex, the facts are also hard to determine. Most males enter the country as agricultural workers and most women become domestic workers, but their actual work might include sexual slavery as well. Domestic work might include conditions of sexual slavery and so might agricultural labour. It’s impossible to determine at what points the lines might blur between the kinds of “work” that the trafficked are brought in to do, regardless of gender. The only thing that’s clear is that trafficking includes but is not limited to sexual servitude. Given the difficulty in determining the exact nature of this indentured labour, how did trafficking become a media story primarily about prostitution forced upon women and girls?

Trafficking became sexy in part because the most vocal anti-trafficking activists are also often those who protest against prostitution per se, arguing vehemently against the concept of sex work: the exchange of sexual labour within consensual relationships. Among these, Donna Hughes, a Professor of Women’s Studies at the University of Rhode Island, has written against the distribution of condoms to prostitutes on the grounds that it would legitimise prostitution. And then there were Nicholas Kristoff’s highly publicised efforts, chronicled in his New York Times op-ed articles in the early part of this year, to “buy the freedom” of two teenage Cambodian prostitutes and return them to their families. Kristoff’s sanctimonious pieces reminded me of Americans who take candy to starving kids in places like India, believing that a few nuggets of crystallised corn syrup might alleviate systemic conditions of poverty and hunger.

Hughes and Kristoff present such personalised narratives about the supposed evils of prostitution with only tangential discussions about the economics of prostitution. Ultimately, their narratives imply that trafficking is only about sex. It’s not that stories about the sexual abuse of trafficked humans and of many prostitutes are not true or relevant, but focusing on the morality of prostitution or on highly individualised stories does not explain the institutional and widespread nature of trafficking. Peter Landesman’s story in the January 25, 2004 New York Times Sunday Magazine further emphasised the sexual aspect of trafficking in highlighting the extent of sexual slavery within the United States. While such facts are important to the public, the cover photograph seemed aimed at our collective Lolita fixation: a young girl in a Catholic School uniform sits on the edge of a bed with bare knees and a bit of thigh tantalisingly exposed. Sex sells, yet while that’s not in itself a bad thing, it seems odd to combine titillation with stories ostensibly designed to alert readers to the oppressive exploitation of women and children.

With regard to sex and trafficking, the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, ratified in 2000, carefully separates forced sexual labour from prostitution. The definition of trafficking is: “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons… by improper mean, such as force, abduction, fraud or coercion, for an improper purpose, like forced or coerced labour, servitude, slavery or sexual exploitation.” And further on: “With the exception of children, who cannot consent, the intention is to distinguish between consensual acts or treatment and those in which abduction, force, fraud, deception or coercion are used or threatened.” It’s clear that trafficking is difficult to track and prosecute without clear guidelines that encompass a range of forced human relations. It’s especially hard to prosecute because most of those trafficked may risk their lives or be criminalised and deported as illegal aliens.

Following the UN Protocol, the Clinton administration passed the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (VTVPA) in 2000. The Act provides for temporary Non-Immigrant T-Visas for victims so that they might file charges against their captors without fear of deportation. The detection and prevention of trafficking is particularly complex because they have to happen within the nexus of international law and domestic policies. Those trafficked may find it difficult to seek redress especially when, as is often the case, they lack the social and economic wherewithal to argue for their rights. For instance, the T-Visa application asks for $200 in application fees alone, along with sundry other filing charges. Since trafficking effectively creates a large pool of slave labour, how is a trafficked person to gather the money to apply for a T-visa? And who are the traffickers and the trafficked? How do people end up within the growing slave economy of the United States and what keeps the system going?

I posed some of these questions to Elissa Steglich, Managing Attorney of the Midwest Immigrant and Human Rights Center, a counter-trafficking project at Heartland Alliance (HA) in Chicago. HA, a Chicago-based non-profit organisation that provides legal and social services for the impoverished, has been working on trafficking approximately since 1996. Staff members came across instances of trafficking in the course of routine work on immigration cases. Without a widespread public recognition of trafficking, H.A’s only legal recourse for victims was to help them claim asylum. In 2000, HA joined the Freedom Network, a consortium of 22 organisations formed in response to the VTVPA. Members recognised that the new legislation would mean renewed efforts to identify and aid those who might not know of the support available to them. They also expanded the definition of trafficking to include mail-order brides tricked into sexual and domestic servitude. With regard to the financial burden of the T-Visa, Steglich informed me that the Department of Justice has been generous about granting fee waivers when applicants are assisted by agencies such as hers. Most of the trafficked, however, work in isolation and are unaware of their rights. For that reason, HA conducts workshops and maintains links with community agencies and activists including those related to social service and domestic violence; they in turn are able to alert HA to instances of trafficking.

In the course of its work, HA and other organisations like the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) have unearthed surprising facts about the demographics of both traffickers and the trafficked, two groups who come from varied educational, ethnic and racial backgrounds. A number of the trafficked are U.S. citizens whose drug dependency and homelessness make them especially vulnerable to traffickers. Those trafficked often owe large sums (at some counts as much as $3000 or more) to the traffickers believing that they are paying for legal visas and that they can eventually earn enough to pay back their debts. Once in the U.S., they are forced into indentured labour and their debts never disappear. Very often, traffickers will threaten their captives with harm to them and their families left behind if they try to escape.

The largest problem in detecting and fighting trafficking, Steglich informed me, is that most people don’t recognise trafficking when they see it and have misconceptions about how it occurs and to whom. The truth about trafficking is that it happens around us every day. Traffickers are rarely the evil men operating out of pure malice as seen in media representations. Many traffickers are part of the immigrant communities they exploit, from places as different as Jamaica and Russia. They are often men – and women – who return to their homes of origin with stories of economic success and promises of taking fellow immigrants towards more of the same. Those who use unpaid illegal labour do so in order to cut costs, and they are as likely to be small farmers in the North-East as large orange growers in Florida. Those who use unpaid domestic labour range from United Nations officials to professionals of various sorts.

Trafficking occurs within our everyday reality, and within the same economy that gives us relatively cheap milk and orange juice because of cheap and abundant labour. We are used to seeing but ignoring the vast numbers of janitors, bus people and farm hands silently working around us, and so it comes as a shock when a case of trafficking is exposed. In 2001, the Ramos brothers were arrested for exploiting 700 workers on their citrus groves in Lake Placid, Florida. The workers were invisible only because labour usually goes unseen in the United States: the vast enterprise operated within plain view of a Golf Club attached to a retirement community.

As Americans, we like our garbage collected on time and we want to pay the least possible amount for groceries. We don’t care to know the truth about the labour that makes all that possible. We grumble when the price of gas goes up and we are especially testy around the issue of outsourcing. Yet even as we worry about “our jobs” being taken away to faceless masses in India and China, we are surrounded by the benefits of slave labour. Commentators often refer to trafficking as the “dark side of globalisation,” but the phenomenon flourishes in the United States for an old-fashioned reason: the need to make profits with minimum expenditure.

To blame trafficking on globalisation and price competition ignores the fact that an economy that actually values human labour and the health of workers would make modern-day slavery untenable. When trafficking seems to be about sex and violence, we are more able to connect with and eulogise the “victims.” We see ourselves rescuing hapless young women and children but prefer not to think about supposedly abstract issues like labour and fair wages, even though those affect us in intimate ways. Trafficking survives because it’s a part of our daily lives, not because it emerges from invisible networks of pure evil. Trafficking is only partly about sex and more about the price we pay for a carton of orange juice.

Originally published in Clamor, Issue 28, September/October 2004. A pdf of the issue is available here.

See also, “American Home: Trafficking and the Return of Domesticity.”

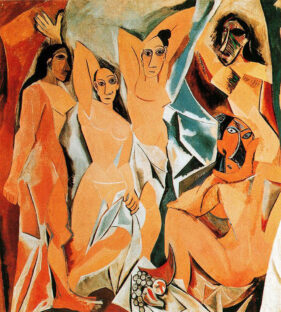

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) – Pablo Picasso