In a book centered on an item that revolutionized sex between humans, it seems odd to disregard its effect on half of them.

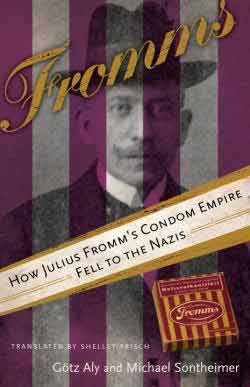

By Götz Aly and Michael Sontheimer; Translated by Shelley Frisch; Other Press; 219 pages

The history of condoms is littered with eye-opening details. According to some accounts, the earliest condoms were linen sheaths used by Egyptians, but it is unclear if they were used for ceremonial purposes or actually used during sex. There are descriptions of condoms made of bone and others made of sheep’s intestines. Until the 15th century, condoms were mostly used for birth control and even then mostly by the upper classes.

With the rise and spread of syphilis, condoms became a necessary part of public-health measures as well as the first barrier, as it were, in nations’ abilities to engage in war. After World War I, 100 percent of German occupying forces were infected with syphilis or gonorrhea. One German military doctor in the Warsaw area wrote about being ordered to “open a brothel for the members of formations that came marching through.”

That last detail appears in Fromms: How Julius Fromm’s Condom Empire Fell to the Nazis, a book that provides an account of the singular condom-manufacturing business established by Julius Fromm in the early part of the 20th century and its takeover by the Nazis. In 1839, Charles Goodyear (yes, that Goodyear) developed the rubber-vulcanization process that was the material basis for condom manufacture, and subsequent innovations produced a dipping method that enabled the mass production of seamless and sheer condoms. But it was Fromm who redefined the industry.

Conservatives who felt they encouraged promiscuity and, worse, family planning regarded condoms with suspicion. But the need to curb the spread of sexually transmitted diseases eventually outweighed moral questions. Fromms was able to benefit from this double-edged cultural discourse and was the first to package his products with all the elegance granted to chocolates. A box of three condoms came in a pretty little box striped with green and purple and cost 72 pfennigs. This was a relatively high price for the time, but the condoms (or “Fromms Act” as they were called in German) came with a guarantee of quality unmatched by any other brand of the time. Each condom was subjected to three inspection processes and eventually dusted with a lubricant that gave them a “velvety surface.”

Fromm’s condoms became immensely popular and the entrepreneur was able to establish himself as the patriarch of a large and extended and well-off Jewish family. Fromm was born in 1883, in the town of Konin, which was part of what was then the Russian Empire. His family moved to Berlin in 1893 into a working-class neighborhood where his father made and sold cigarettes, an occupation undertaken mostly by impoverished immigrants. The entire family pitched in, and eventually they all changed their names to seem less Jewish. The second-oldest son Israel thus became Julius. But some years later, his first one-man company was named “Israel Fromm, Manufacturing and Sales Company for Perfumes and Rubber Goods.” Aly and Sontheimer deftly evoke the ways in which Fromm, like so many Jewish immigrants in Germany, constantly negotiated their identities in a society whose anti-semitism lay always simmering under the surface, long before the brutality of the Nazis made it come to a head.

The company became spectacularly successful; by 1931 it was producing more than 50 million condoms. In 1933, Hitler became Reichskanzler and Fromm, who had assiduously avoided politics and been naturalized in 1920, now found his firm threatened with takeover and began reluctantly the laying the ground to emigrate. Fromm’s citizenship was denied, and Hitler’s government possessed the company. The process whereby that happened was a convoluted one, and while the financial details are somewhat dry they provide a critical perspective on the Aryanization process that engulfed Germany at the time.

Fromms is a complex portrayal of a man whose life philosophy appeared relatively simple but efficient. Julius Fromm, by most accounts, adhered to a strict work ethic, treated his workers well and was responsible for innovations beyond the products he made. Aly and Sontheimer dedicate an entire chapter to the architecture of the firm’s headquarters, revealing that the building, designed by Arthur Korn and Siegfried Weitzmann, presaged what would become the ubiquitous use of glass in the facades of modern buildings.

The book falters in its consideration of gender. This is not a cultural history of the condom, but initial sections do consider the social relevance of rise in their use. Here and in other places women emerge as marginal figures. The authors begin with an intriguing statement about Ruth Fromm’s dislike for her uncle Julius, but never follow up on a promise to reveal more about that. The account of Korn and Weitzmann’s collaboration contains an abrupt statement that “the friendship between these two architectural masters came to an end in 1937 because of a woman.” An endnote refers only to some correspondence, but we are given no details in the text and left only with what appears to be a classic case of misogynistic blaming of a woman for the end of a creative collaboration between men (think John, Yoko and the Beatles) . The authors are preoccupied with the issue of disease but have almost nothing to say about the advantages condoms presented to women in their pursuit of sexual freedom. In a book centered on an item that revolutionized sex between humans, it seems odd to disregard its effect on half of them.

Originally published in Windy City Times, February 24, 2010.