I’m late to a lot of phenomena and Taylor Swift is one of them. I listened to some of her work a couple of years ago, when there seemed to be a pronounced hatred of her, and it wasn’t hard to see how much of it was motivated by misogyny and a general contempt for young people. That so many of the young in this case appear to be mostly white women seems to give some people an excuse and an opportunity to exercise their sexism in public: Swift’s critics seem smug in their knowledge that they’re likely to face much less backlash for their criticisms (few of their pronouncements amount to reasonable critiques) when their target is a wealthy white woman. And all that being said, I’ve heard about Swifties and I know that this is not a crowd I want to tangle with—I’ve experienced enough venomous anger from members of the Beyhive to know that there’s nothing quite like the fury of angry superfans to (almost) turn you into one of those grumpy white men bitching that music was better in their day. My crime was daring to suggest that Lemonade, far from being some lyrical work of art, was a tired paean to the idea that marriages, especially between extraordinarily wealthy people, need to last forever because, love, or whatever.

But, yes, Swift. Time recently named her “Person of the Year.” It’s a completely meaningless accolade, and the, ah, award has all the cultural impact and relevance of a sequined paper tiara handed out at a toddler’s tea party. We might recall that previous awardees have included Elon Musk, Rudolph Giuliani, and George W. Bush. Those who object so strenuously to this naming are even more furious at the idea that Swift will have an entire course devoted to her at, gasp, Harvard.

Which is how Swift came to my attention again this past weekend: on social media, more than a few people seemed irate that there was not only a course on Taylor Swift but at Harvard, damn it. The news is not that fresh but the ire rises anew every now and then. The implication—actually, the outright statement by many—was that surely someone paying to go to that institution should only be steeped in Mozart and Bach and all forms of Classical Literature.

This is the kind of ridiculously retrograde political and cultural mindset that never seems to fade away, no matter the decade. The New York Times has interviewed the professor in question, Dr. Stephanie Burt, and it seems like an interesting course. Addressing her critics, Burt says, “[T]hey should remember literally everything that takes up a lot of time in a modern English department was at one point a low-prestige popular art form that you wouldn’t bother to study, like Shakespeare’s sonnets and, in particular, the rise of the novel.” She’s right, of course, and the same is true of music.

It’s not as if there have never been any courses on what’s often referred to as “popular culture” (it would take too long to express my irritation with that phrase here but I’ll just say, for now, that I find it reductive and useless). People have been teaching courses on Madonna for nearly as long as she’s been around, for instance, and a lot of the current blah-di-blah about the Time award and the course is about media needing to find eyeballs to migrate to websites.

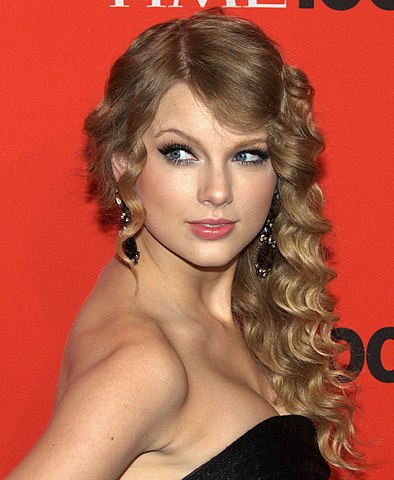

Swift is very, very good at what she does—and if you think it’s easy to create her kind of music, fine, you come up with a “Shake It Off” or an “Anti-Hero.” As with every other kind of superstar, her success is a result of several different factors, including her incandescent whiteness, her seeming approachability, and a massive media machine that carefully matches her public persona—and her three famous and wealthy cats—with her fan base, one with which she has very, very carefully and assiduously cultivated a long and near-intimate relationship. Yes, of course, all of that is part of the manipulation of contemporary stardom, and it takes on a particular kind of stickiness in the age of social media that can verge on the outright dangerous. Swift is also especially well known for her public statements on the matter of artists and their ownership of their material, most famously in the dispute over the masters of her work.

All of this gives us several different ways to think about the times we live in through the lens of Taylor Swift. The legal conflicts over ownership of her material provide a way to think through the thicket of questions surrounding intellectual property and the matter of property “rights” in an age of streaming and TikToks. (And the question of who owns her work should not descend into a celebration of girlboss feminism but involve a discussion of Swift’s place in forms of predatory capitalism). 1Many thanks to Avram Rips. Her relationship to her fans and the responses to it and them—and, of course, her—raise questions about gender and whiteness, and persuade us to think more deeply about the nature of fandom as both a natural expression of joy in someone’s work and a carefully manipulated media creation (consider, for instance, the persistence of “parasociality”). The contempt in which so many hold her music and lyrics as insignificant because they’re too popular leads to a world of questions about the very nature of taste and taste-making. And in these economically troubled times where the average undergraduate is convinced that the only career available upon graduation is that of an influencer, critically analysing the networks of power and influence that make Taylor Swift, well, Taylor Swift helps to demystify the idea of instant and uncomplicated celebrity.

Which is to say: the emergence of Taylor Swift as a cultural phenomenon helps us better understand how capitalism works, especially in its embeddedness in seemingly affective frameworks like fandom and celebrity.

The only answer to the question,“Why would anyone teach a course on Taylor Swift?” is, “Everyone should take a course on Taylor Swift.”

See also: “A Gauntlet of Lesbians: In Praise of the Middlebrow.”

And Nathan J. Robinson is right to suggest that Swift would be a better choice for president: see his “There’s Only One Person Who Can Unite This Nation: Taylor Swift, 2024.”

Yasmin Nair is a fan, but not a Swifty.

This piece is not behind a paywall, but represents many hours of original research and writing. Please make sure to cite it, using my name and a link, should it be useful in your own work. I can and will use legal resources if I find you’ve plagiarised my work in any way. And if you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.