“Within the next couple of years, we’re going to have a million sex offenders, people found guilty or who plead guilty. That’s an enormous population we’re going to isolate from mainstream society.”

Originally published in Windy City Times, August 5, 2013

This article was written as part of the Windy City Times special investigative series: LGBTQs and the Criminal Legal System.

In 1977, Anita Bryant launched her crusade against a recently passed Dade County, Fla., ordinance that banned discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. As the leader of a coalition named “Save Our Children,” Bryant and her supporters tapped into an old perception of gays as sexual predators of children.

In a now-famous statement, she declared, “As a mother, I know that homosexuals cannot biologically reproduce children; therefore, they must recruit our children.” Bryant’s campaign led to the repeal of the ordinance but paradoxically also became the beginning of the end of her career, alienating her from some conservatives and liberals alike.

In the years since Bryant’s campaign, there has been a palpable shift in cultural responses to gay and lesbian issues, with several polls indicating greater support for issues such as marriage equality. But the figure of the gay man in particular as a sexual predator still haunts culture and continues to re-emerge.

In 1955, Boise, Idaho, erupted in a sex scandal where nearly 1,500 men were questioned about allegedly having coerced underage young men into sexual acts. There was no such sex ring, but countless lives were scarred forever.

This April, as the gay marriage debate reached the U.S. Supreme Court, two married gay men in Connecticut, George Harasz and Douglas Wirth, decided to fight charges that they had sexually abused children in their care. In a sign of how differently such cases are still treated in the mainstream press, the website Gay Star News’ headline stated, “Gay couple accused of child abuse go to trial to clear their names.” New York’s Daily New headline ran, “Gay Connecticut couple accused of raping adopted children will face trial.”

Since 1977, sex offender registries (SORs) have been instituted in every U.S. state, ostensibly to prevent sexual abuse of minors and others by tracking everyone convicted of sexual abuse.

But according to a growing number of critics across the political spectrum, SORs have also increased so much in scope, by including even acts like public urination in the category of sex crime, that they’ve become virtually meaningless. In addition, SORs place so many residential and vocational restrictions on offenders that larger numbers are unable to return to society with places to live and stable systems of support.

In Illinois, registered sex offenders cannot live within 500 feet of any school buildings or have trade licenses. Illinois also mandated in 2011 that the licenses of medical and health professionals convicted of sex offenses can be permanently revoked without a hearing. Increasingly, many offenders across the country simply end up homeless.

The term “sex offender” is rarely uttered at gay and lesbian public events, raising as it does an old and timeworn stereotype that still causes fear because of its automatic association with terms such as “pedophile” and “sodomite.” To date, none of the major gay and lesbian organizations has explicitly taken a position on issues concerning sex offender registries.

But there are in fact gay sex offenders on the registry, and there have always been widely sensationalized cases of alleged and real sexual abuse of children by men who also identify as gay.

Tracing the specific effects of sex offender registries on LGBTQ people reveals that both terms, “LGBTQ” and “sex offender,” are fraught with multiple tensions and definitions. For instance, not all people convicted for sex offenses are LGBTQ, but the sexual acts, such as oral and anal sex, which place them on the registries are defined as “crimes against nature” in certain states.

The circumstances in which LGBTQs find themselves on sex offender registries both challenge the applications of such terms and hark back to older and still-prevalent ideas about sexual minorities.

The fact both sex offenses and sex offenders fall into such diverse and disparate categories also explains why it has been hard to mobilize a concerted political movement against the prevalence of SORs.

U.S. sex offender registries: A brief history

In 1989, 11-year-old Jacob Wetterling was abducted from his hometown of St. Joseph, Minn. Wetterling was never found, but his disappearance prompted concern that there was, at the time, no verifiable database of sex offenders.

The Jacob Wetterling Act of 1994 was designed to create a registry that could enable easier tracking of sex offenders. Megan’s Law, an amendment to the Wetterling Act, was named for Megan Kanka, raped and murdered by a neighbor and convicted pedophile in 1994. The amendment created the Community Notification System, which requires all convicted sex offenders to register whenever they move and on a periodic basis.

The federal Adam Walsh Act, or AWA, was passed in 2006 and named for a six-year-old abducted from a Florida mall in 1981 who was later found decapitated. States are expected to comply fully with the AWA or incur penalties for noncompliance.

As this goes to print, an Illinois bill, SB 1643, which with proposed amendments would bring Illinois into full compliance with the AWA, is under review and has just been listed as “postponed,” but it is widely expected to pass. With the proposed amendments, the bill would change current laws to make stricter requirements that place greater financial and social burdens on offenders and make it harder for them to reintegrate. Provisions include forcing “sexual predators” to register every 90 days for life, and persons convicted of misdemeanor offenses to register annually for 15 years.

In 2007, Human Rights Watch, an international nongovernmental organization which researches and advocates on human rights issues, issued a 146-page critical paper, “No Easy Answers.”

The HRW paper called for a massive overhaul of the AWA, including terminating public access to information about sex offenders’ places of residence, information that has been used by people in search of vigilante justice to intimidate and even kill sex offenders.

In June 2012 in Washington state, a man named Patrick Drum shot and killed two convicted sex offenders; the first was his roommate. When police tracked him down, he admitted that he had planned to kill sex offenders until he was caught.

The HRW piece acknowledges the need to prevent sexual abuse but questions whether the AWA’s reach and stringency help or hinder the quest for justice. The AWA contains sweeping and detailed provisions, including those targeting juvenile sex offenders, and places conditions and restrictions stricter or more costly than what states might want or can afford to enact—such as expensive GPS monitoring systems.

So far some states are refusing to comply with the AWA, usually because of the high costs. California, for instance, has decided that the noncompliance penalty of $5.6 million annually is less than the costs of implementing the AWA, $32 million a year.

In 2002, U.S. Justice Department statistics indicated that recidivism among sex offenders is much lower than originally projected, about 5.3 percent, and studies indicate that most child sexual abuse occurs at the hands of family members or people known to victims.

According to HRW, the U.S. has the most punitive and wide-ranging set of laws for sex offenders, and South Korea is the only other country that has community notification laws.

For LGBTQ people on the registry, registration can mean a shame and stigma that many worked to overcome on account of their sexuality or that others may have understood only as a historical fact. For those living in already small communities, it can mean a drastic shrinking of their worlds and a heightened sense of danger as they fear retaliation based on a combination of their sexuality and their recorded offenses.

Time spent in prison, where gays and child molesters are considered fair targets, can be especially dangerous for LGBTQ offenders, and more so in a culture that already naturalizes prison rape as inevitable.

LGBTQs on the registry

The presence of LGBTQ people on sex offender registries is hard to detect, since demographic information says nothing about victims except their ages.

The details provided include criminal legal categories (such as “sexual predator” or “murderer”), the legal terms for their crimes (“aggravated criminal sexual abuse” or “murder with intent to kill”), and their ages at the times of the crimes.

Jeff Haugh, a gay man, recalled the morning of March 14, 2002, when he was awakened by FBI agents who interrogated and arrested him on the charge of having received child pornography the prior year.

Haugh would later find out that he was swept up in the Candyman sting, set up under U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft in 2002 and named for a Yahoo.com porn e-group. The operation resulted in the arrests of 40 men across 20 states.

The controversial image was of a man and a little girl, and he told the FBI, “I’m gay, this isn’t even something I’m interested in.” Haugh had been sent the website link by someone and, he said, he immediately deleted it: “But they arrested me on the street five hours after they showed up, for something I’d seen on the Internet a year before.”

Haugh, who is now 64, owned the house he lived in, but when he came out of his five-month sentence and a stint in an Indianapolis halfway house, he found the residence had been “vandalized and torn to shreds.”

He currently lives on the $800 he gets in Social Security, after a lifetime of travel and work. Prison was difficult because, he said, “people figured out I was gay. They think you’re a child molester automatically if you’re gay.”

Although Haugh was never charged with physically harming anyone, and although his crime is listed as “child pornography/film/photos,” his online registry information records a victim of the age of 13, and him as a “sexual predator.”

The term “sexual predator” is defined by a wide range of actions, including possessing child pornography and sexual assault. It can also include “public indecency” for a third or subsequent conviction. Public indecency can also include urinating in public, and there have been several recorded instances of people registered as sex offenders for that act.

“Brett,” who asked to use a pseudonym, was also, like Haugh, swept up in the Candyman sting.

He said he didn’t remember joining that particular group, but had “downloaded thousands of pictures” from other places. Of these, 33 were deemed to be of minors under the age of 18.

For Brett, the arrest, which sent him to the Butner Correctional Complex in North Carolina and into a sex offender treatment program, meant an immediate end to medical school.

He was also part of the controversial study which emerged from Butner, stating that as many as 85 percent of convicted Internet offenders had committed acts of sexual abuse against minors.

“I felt like I had to give them what they wanted, because I didn’t want to get kicked out of the program,” he said.

In comparison to what many LGBTQ sex offenders report going through, Brett felt insulated and somewhat protected because he was in a special program. But, “for me, it was still prison, and it was difficult being away from my family.”

Brett had not been very out as a gay man prior to his arrest, and the end of his prison sentence left him wanting more connection to the gay community.

“I would probably try to be more active in the gay community but for my conviction. If I didn’t have that, I’d want to be more of an activist,” he said.

Brett has found a job as a paralegal, but he feels the daily weight of the restrictions on his mobility. Once an avid tennis player, he has stopped playing, because most courts are in parks.

For these Illinois men, the restrictions, which tie them down in terms of both physical and social mobility, are the hardest aspects of the registry. Brett also added that Illinois especially overuses the term “predator,” which can make people seem more dangerous than they are: “If you go online, over 50 percent are listed as predators. Nobody in Illinois wants to get rid of [the word] ‘predator’ [as a legal category].” Brett and others feel that the term is applied too loosely, and only increases the stigma for those who may not fit the stereotype. Echoing the thoughts of many, he also said, “The registries have lost their intended purpose anyway—if you register everyone for everything.”

In 1997, Richard Hunt of Massachusetts was arrested for what he described as an “offense against an 11-year-old boy.”

“I was 20, I should have known better,” he said. But Hunt also said, “It wasn’t a Lifetime movie. It was not what people think, the rape of a child. It was not brutal but also not innocuous, not what people want to imagine.”

Hunt likens being on the registry to having a chronic illness.

“It informs every decision you make in your life and how you go about your daily business when you think about it,” he said. “People hate you; they want you to die and go away.”

He describes getting a job and housing as impossible. He managed to put himself through four years of state college and then two years of graduate work at Brandeis University, before notification requirements made that difficult.

Today, Hunt cobbles together a living working for an older gay couple whose house and gardens he looks after. He considers himself fortunate in having a connection with the older gay community, which has been, according to him, more supportive than many young people in the community.

Frustrated with a lack of online resources and help in navigating the system, he set up a blog, [masexoffenderresource.blogspot.com/&; which he hopes to turn into a resource book.

There are fewer women than men on SORs, but the effects are as far-ranging.

Rebecca Curtis, of Luray, Va., was 21 when she, as she put it, fell in love with a 12-year-old girl who was also the daughter of the man drywalling her home in 2004. Today, the two are married.

Curtis said that the girl’s mother neglected her and told her she could have her daughter move in with her for $500, claiming she needed the money for bills and rent. (Curtis also said that the woman offered to sign over full guardianship for $5,000 but that she refused.)

Over the next few years, Curtis and the young girl developed a sexual relationship while they lived together, until the mother filed charges against her—Curtis claimed this was an attempt to deflect attention from having left her 4-1/2-year-old son unattended for two hours.

Curtis was convicted as a nonviolent sex offender in 2007, but when Virginia laws changed to comply with the AWA, she was recategorized as a violent sex offender.

The relationship continued, and they eventually married in Washington, D.C.; Curtis’ wife is currently five months pregnant.

Being parents will not be simple for Curtis and her wife, since Curtis will be banned from gatherings that include children.

Such cases represent a range of ways in which LGBTQs can find themselves placed on sex offender registries. Both Haugh and Brett were targeted in the kind of chat rooms in which gay men in particular often find themselves. Intergenerational sex and the issue of consent between adults and minors are still topics that the gay community has never fully reconciled satisfactorily, and the conversations are gendered very differently. For women, who feel more at threat from sexual violence because of what many call “rape culture,” and from a general cultural reluctance to think of women’s sexual agency in terms of desire, the question of sex between minors and adults is a more fraught one. Intergenerational sex has a longer cultural history among gay men, where the issue has been more of a topic of conversation, until relatively recently.

Neither Hunt nor Curtis is likely to find many sympathetic audiences in the younger gay community. As Hunt put it, the work of Wilhelm von Gloeden, the German photographer famous for his nude studies of young Sicilian farm boys, graces the walls of many gay homes, but the subject of man-boy sex is still a forbidden one.

Patty Wetterling , mother of the child after whom the Wetterling Act was named, has been outspoken about the problems she now sees with SORs. “We need to keep sight of the goal: no more victims,” she said. “We need to be realistic. Not all sex offenders are the same. We need to ask tougher questions: What can we do to help those who have offended so that they will not do it again? What are the social factors contributing to sexual violence and how can we turn things around?”

Currently, it’s not just parents such as Wetterling but even organizations in support of SORs that echo similar questions about how far they have been extended. On its website, the group, Parents for Megan’s Law, fully supports SORs and the need for “arrests for non-compliance and increased accuracy of registry information.” However, it has also posted a letter from its director, Laura Ahearn, pointing out that residency restrictions may have gone too far: “Enacting ill conceived politically correct in the moment laws may lead to a constitutional challenge, bringing invited attention to the lawmaker but seriously compromising existing laws. More importantly, it will lead to a greater number of homeless and non-compliant sex offenders—exacerbating their tracking, monitoring and supervision—ultimately placing our children at greater risk for victimization.”

Scholars and activists have differing opinions about how SORs became what they are, and what needs to change, but they’re united in opposing the current state of things.

‘They Need to Go’

Corey Rayburn Yung, a law professor at the University of Kansas, has studied the rise of SORs. Yung argues that the there is a war on sex offenders as much as there was and still is a war on drugs.

Speaking to Windy City Times, Yung said, “Within the next couple of years, we’re going to have a million sex offenders, people found guilty or who plead guilty. That’s an enormous population we’re going to isolate from mainstream society.”

Yung expanded on the similarities between the war on drugs and the war on sex offenders: “In some African-American communities in places like California, under the war on drugs, half of African-American males between the ages of 18 to 26, are either currently in the prison system or the criminal justice system more broadly, or were in the past. You have communities where the men in particular are now tagged as criminals and have their employment options diminished and are left to fend for themselves. That same phenomenon occurs with sex offenders.”

A lesser-known aspect of sex offender registries is that sodomy statutes can still play a role in ensnaring people in them. Some states still have sodomy laws on the books, and those are all states that had them in 2003 as well. The U.S. Supreme Court case of Lawrence v. Texas in 2003 addressed sodomy as a private, consensual act between adults, but that means that commercial acts of sex, such as prostitution, and perhaps anal and oral sex between minors can still be prosecuted.

Yung said that “crime against nature” statutes include sodomy and bestiality: “In those states in particular, they’ve not removed these statutes from the books, because, as they argue, bestiality is still a crime. But then it turns out they’ve done a lot of targeting of gay and trans communities in some cases, using these laws that were thought to be struck down in Lawrence v. Texas.”

In some prostitution cases, undercover police officers target gay male prostitutes for acts involving oral or anal sex, defined as sodomy—and which brings longer prison sentences and sex offender registration. Yung also spoke of a Virginia case involving minors, 14 or 15 years old, prosecuted for sodomy, where the courts declared Lawrence v. Texas couldn’t apply because they weren’t consenting adults.

Yung pointed out that it was difficult to gauge how many people who committed sodomy crimes before Lawrence v. Texas might still be on sex offender registries. “But there certainly are people who engaged in consensual sodomy and are on the registry,” Yung said. “Given that so many of our sex laws have overwhelmingly been used to target sexual minorities, it’s not surprising that there’s going to be a lot of people left over from that era and continuing criminal laws that are in LGBTQ communities.”

For Yung, moving forward and away from overreaching sex offender registries means using more resources “in terms of imprisonment and also in terms of police investigation for the more heinous of our sex crimes, rape and child molestation.” He pointed out that, “right now, rape continues to be one of the most underprosecuted crimes” and that his own work on SORs had come about because of his interest in studying how to combat sexual violence in particular.

The issue of sexual violence strikes close to home for Jason Lydon, a founder of Black and Pink, an organization of LGBTQ prisoners and allies on the outside.

Lydon spent six months in federal prison for civil disobedience against the U.S. Army School of the Americas (now the Army’s Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation). His experience in prison, where he says he was sexually assaulted, did not change his politics regarding prison abolition. Like many queer radical prison activists, including Angela Davis, Lydon believes that the prison system—which activists refer to as the “prison industrial complex”—serves no purpose other than to make profits for the state and private companies.

Lydon’s appraisal of sex offender registries comes from what he calls “a critique of the idea that the state can protect people and create authentic safety.”

“My immediate response [to SORs] is as an abolitionist: This is not going to bring us forward to transformative justice,” Lydon said. “They need to go.”

Lydon said that his experience with sex offender registries comes from his past work as a Unitarian Universalist minister, in which he spoke openly about the need to have frank conversations about adult-minor sexual relations, as well as from knowing several friends on SORs.

Aware of his views, a member of his congregation approached him to talk about the member’s own sexual desire for children. Lydon said that, “as a minister and mandated reporter, I had to think about what information I could and couldn’t hear, how I could be supportive of him and what that would mean, I was able to gather that he wasn’t in physical contact with children. So we talked about his support and got him in to see a counselor.”

Lydon wants to see more conversations about the age of consent.

“I do have a value judgment if someone is under puberty, I don’t believe there can be consent with an adult,” he said. “I think that young people’s sexuality with other young people can be mutually fulfilling and doesn’t need to be policed by adults. But I do think we need to have open and honest conversations about what consent looks like and where age and power dynamics play into that, how alcohol and drugs play into that.”

Alan Mills, legal director of the Uptown People’s Law Center in Chicago, works with clients on sex offender registries and sees no value in those registries.

“I think they should be scratched, but I don’t think that’s politically possible,” he said. “[They] should be brought back to where they started, which is to list pedophiles. The realistic solution is to work with victim advocate communities to try to work on the ‘smart on crime’ rhetoric. Unfortunately, it’s far too easy for politicians to be ‘tough on crime.’ If you talk to them off the record, most of the legislators in Springfield will admit that what we’re doing with sex offenders makes no sense whatsoever.”

Mills does not think the critical conversation on SORs has made its way into the general public.

“Registries seem to be the in thing now,” he said. “It’s easy, cheap, and it gets votes.”

Erica Meiners, a professor at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago, is also a co-founder of St. Leonard’s Adult High School, an alternative high school for formerly incarcerated men and women.

She’s also the author of several books and articles that address the intersection of LGBTQ politics, the prison industrial complex, and public education. She has, in both her research and activism, encountered people trying to get back to normal life after prison and while on the registry.

When asked if sex offender laws might deliberately or inadvertently target LGBTQs in particular, as in gay chat rooms, Meiners pointed out they’re not the only ones affected by the law’s relationship to sexual identity.

“The people I interact with may or may not identify as non-heterosexual but may engage in non-heterosexual or non-gender-conforming sexual practices, including sex work that then makes them more vulnerable towards being picked up by police, being under surveillance, where they can live or move, how their bodies are seen in particular locations in the city,” Meiners said. “So that’s in addition to gay men being targeted in chat sites or the idea of gay male sexuality as predatory being recirculated.” For Meiners, it’s important to consider how sex offender laws are set up to target the most vulnerable among us.

Meiners spoke about a need to do two things at once. The first is to develop ways for people harmed by sexual violence to recover from the trauma. The second is to make sure that those who inflicted the violence are held accountable without society’s resorting to harsh and long-lasting measures such as sex offender registries.

“There’s no evidence that registries are successful in preventing sexual assault or transforming our larger culture or that they stop sexual violence,” she said “And people who have to lodge complaints often find themselves violated by the system itself.”

Meiners called SORs “the ideological scaffolding” that has pushed prison expansion in the past decade.

“That expansion has happened with such little critical interrogation from the general public and also queers as we march towards assimilation,” she said. “Now is a politically important moment for LGBTQ people to interrogate these claims of protection being made, who benefits from them, who doesn’t. Because decades ago, those claims were being leveled against us.”

WCT contacted groups strongly in favor of sex offender registries, but they were not able to respond in time for publication. A later piece, on sex offender registries and HIV-disclosure laws, will return to this topic.

The crime series continues in next week’s Windy City Times.

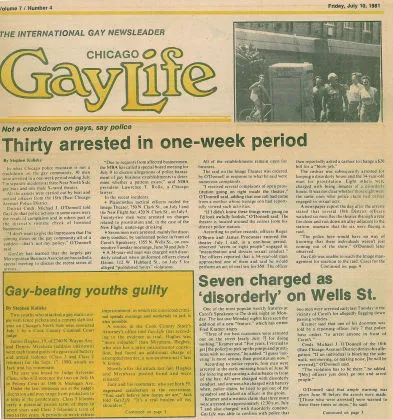

Photo Caption: These two GayLife stories from July 10, 1981 show that arrests used to be very common at gay bars and in public spaces, and these arrests may still be on the records of some people today.

See related story at www.windycitymediagroup.com/lgbt/Florida-lesbian-teen-charged-with-sex-crime/42930.html .

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

Dear Windy City Times,

Thank you for the excellent collection of archival materials and for discussing the verboten subject of the connection between homosexuality and the registry in the first set of articles in yourCriminal Legal series. I look forward to seeing what you have in store in the next installments.

There is one important point to note. The article, Bars for Life, starts the history of the registry in 1994 with the passage of the Wetterling Act. But the Wetterling Act was just the federal government getting in on the growth of state registries across the country that started in California in 1947. This was the McCarthy era and the registry was used throughout the 1950s and onward to harass homosexuals. Ninety percent of the people on the registry in that period were adult men convicted of engaging in or soliciting sexual activity with another adult man. With the decriminalization of sodomy in the late 1900s, culminating in the 2003 US Supreme Court Lawrence decision, the focus of the registry gradually shifted from homosexuality to pedophilia. For more on the history of the registry and its homophobic roots, you may find my report on the subject of interest, atwww.SOLresearch.org/SORorigin .

The Bars for Life article also says that the Adam Walsh Act was also passed in 1994. This is obviously just a typo; the AWA was passed in 2006.

Again, these comments aside, thank you for your excellent investigative journalism.

Best regards,

Marshall Burns, PhD

SOL Research

Originally published in Windy City Times, August 5, 2013