Naming power isn’t really enough if the primary aim is to simply shift power around, and #MeToo’s supporters and “leaders” haven’t really done all that much to change that conversation.

This was meant to be a very short piece expanding on an observation about “human nature” and the problem of dealing with it in the wake of recent accusations of sexual assault levelled at Asia Argento and Avital Ronell. It became a slightly longer one about the #MeToo “movement” in general. Consider this a precursor of sorts to a much longer piece on that issue.

When it first erupted into public consciousness, seemingly on a global scale, #MeToo, a hashtag masquerading as a movement, appeared to disrupt the social order and the status quo. We were told, repeatedly, by media outlets shell-shocked by the scale and depth of revelations, that things would never be the same. The world had shifted on its axis, and we were well on the way to gender parity. So we were told.

There are several problems with #MeToo, not the least of which is that, as we repeatedly refuse to learn, a hashtag is never a movement. The promise of social media is that everyone is paying attention — but not many bother to ask: what exactly is the nature of that attention? Who, exactly, is paying attention? Sure, there are 2.3 billion “active” users on Facebook, which means that approximately a third of the planet’s population can, potentially, watch a video of that wildly embarrassing drunken rant you delivered at your cousin’s third and very extravagant wedding. (And, really: a third marriage, sure, but a third wedding? This is foolish optimism melded with capitalism, you wanted to scream, and you did). What none of those (often expensive) “social media consultants” who urge us all to “amplify” our “social media presence” will admit is that an “active” user might simply be someone who logs on a lot to post or watch puppy videos or to keep up with news about their friends and relatives or to follow random links down various virtual rabbit holes. In this context, “attention” is fragmentary at best, swaddled in a jumble of posts and distractions that make sustained movement-building impossible. What social media can do is produce short waves of outrage, which simulate attention but hold no long-term possibilities for effecting change.

Of course, #MeToo is more complex and has served to help many women voice their horrific experiences. And this is not to disparage the many different sorts of stories that the current moment in time has brought us, or to doubt the importance of the revelations that have continued to explode (I’ll have more on all that later). But one of the biggest problems with #MeToo has been how deftly it has positioned sexual abuse as a gendered matter, as something mostly about men exploiting and abusing women. Gender does matter, profoundly, but as most left feminists and queers (of the left and the non-left variety) have known for decades: abuse takes multiple shapes and forms. Still, another problem with #MeToo is that it is ultimately far from being a materialist dismantling of power structures. If anything, #MeToo, with its endless demands that the prevailing order be repaired does not ultimately ask for, dare we say, an abolition of current systems. It asks that women be inserted into more positions of power rather than, say, questioning why such power exists in the first place. A Forbes article notes, approvingly, in the vein of much of the coverage around Time’s Up, the legal fund for victims set up in the wake of #MeToo, that women will now gain more parity in pay. The trouble is, the “pay” we speak of in Hollywood refers to vast and sometimes unimaginable amounts in an industry where profits are counted in the millions (a billion is the new ten million, or something). In this context, Forbes notes, disapprovingly and with what is, in the mainstream, proper feminist ire, that “Emma Stone, 2017’s highest-paid actress, banked $26 million pretax between June 1, 2016, and June 1, 2017. Not too shabby, to be sure, but still 2.5 times less than the $68 million Mark Wahlberg, the highest-paid actor, took home.”

Yes, but who needs $26 million, who needs $68 million, and who needs a world where such amounts are the benchmarks that determine “parity”?

Let me be clear: if someone, say, Mark Wahlberg, wished to give me, say, $20 million, I would receive it with astonishingly good grace (and probably spend most of it on stinky cheese and sushi). But if you put me in charge of determining payscales in Hollywood, I would feel compelled to look over at the entire crowd sitting at the Dolby Theatre during the Oscars and say, “Listen, none of you need more than one home each, and all your finery is borrowed anyway. And starting tomorrow, you need to bring back LA’s once famed public transportation. And use it. Starting tomorrow, you’re all on union wages.”

But I digress, somewhat. Gender, in other words, remains part of a firmament of power and the larger conversation about sexual abuse has done little to question the larger structures that make abuse possible, in different and complicated ways, all of which need to be expanded on and will be, in later pieces here.

For now, I will simply state that all of the above has resulted in a general sense of shock and bewilderment (and, undoubtedly in some quarters, elation) about recent accusations of sexual abuse where women are the alleged perpetrators. One is, in her circle, a famed feminist theorist and queer, Avital Ronell, and the other is someone continuously referred to as a “leader in the #MeToo movement,” Asia Argento. Both face accusations of abuse from younger men with whom they had been in positions of power, each functioning as mentors to accusers. Both have denied the charges, and their denials — and the support of their various tribes — have incurred much criticism for replicating the vicious victim-blaming tactics employed by men like Harvey Weinstein (Argento’s abuser who is also accused by several other women).

Responses to the cases have been varied and reveal much about the generally contentious nature of sex and gender today. I’ll be writing a separate piece on Ronell but for now I want to focus on the different ways in which commenters and others have sought to explain away the two women’s alleged actions. In The Atlantic, Hannah Giorgis writes, “The sharpest #MeToo movement leaders have long named power—rather than gender— as the primary factor enabling abuse.” Well, yes, but naming power isn’t really enough if the primary aim is to simply shift power around, and #MeToo’s supporters and “leaders” haven’t really done all that much to change that conversation.

Bari Weiss, the always-controversial New York Times columnist, has painted the Argento matter as a problem of hypocrisy and, certainly, as she points out, it is striking that Rose McGowan, who once insisted that all victims should be believed is now urging that everyone “be gentle” with her friend Asia Argento. Based on conversations with friends in my own left-queer-feminist circles, I can see the explanations for Argento beginning to bubble up and they will take familiar routes: capitalism is to blame, somehow, or that it’s not uncommon for those viciously abused to themselves become abusers, and so on. None of that is necessarily untrue: the stress of workplace exploitation alone can distort human relations and any child who has been beaten by an abused mother can confirm, even at a gut level, that abusers often repeat their abusers’ patterns on those more vulnerable than them.

But. Frankly, I’m tired of all the explaining. I’ve written before, here, about the failure of the left to go beyond a constant cycle of explaining and understanding. In a world like the one I occupy, where restorative justice practices can (and, I believe, should) be used, holding the accused in the same protective sphere as the accuser is an essential part of making people whole again. There are, often, instances where this can be a necessary part of the process of justice, one where an abuser gains both clarity and empathy.

But. I’ve been up close to abusers about whom I’ve said, “This one’s bullshitting us and is beyond repair.” But the belief that there is a reason for the abuse, and the belief that the reason needs to be explored are both entrenched among some, which gave the abuser an opportunity to play the game, to simulate deep contrition, to speak in the requisite language of “healing” — and to move on to replicate that behaviour in other places.

All of which is to say: sometimes — perhaps always — justice requires us to believe that sometimes, people just do what they do because they are utterly, completely horrible people. So far, whether it’s about “believing all women/survivors” (a tactic I think is fundamentally wrong and prone to engender all kinds of abuse) or expecting every accuser to be a perfect person and every accused to be an ogre (literally what Weinstein has been called), we’ve only created demands of exceptionalism and black and white portraits of goodies and baddies. It may seem that saying that abusers might just be horrible people buys into that same narrative but what I mean is this: the fact that people are flawed and not perfect doesn’t mean that we need to waste our time thinking through the processes by which they got to be that way. Understand what the harm has been, to whom it has been done, and what works best to repair any damage. But spending time trying to understand why Asia Argento may have done what she is accused of doing or why Avital Ronell, with all the academic power at her disposal, might have chosen to torture a hapless graduate student is pointless.

There are and will always be occasions where both abusers and victims (even those terms do little more than establish a peculiarly binary relationship) need time and space to comprehend the enormity of what happened and where all concerned emerge stronger. But then there are times when you just look at someone and say, “You’re full of shit, and you’re not worth our time. Pay your dues and move on.”

Human beings are, in general, horrible people. If we did a better job of recognising that, we’d be less shocked at the horrors we perpetrate and more focused on making sure that less harm happens in our midst.

This is the first in a series on #MeToo and academia. See also “Judith Butler and the MLA.”

Forthcoming: “Avital Ronell and the Death of Queer Theory.”

Yasmin Nair is a writer, and is amenable to a $20 million donation. $10 million would be fine too.

Writing is my primary source of income. If you’ve liked this piece and would like to support me, please donate or subscribe. Subscriptions will help support my writing on a steady basis. You can find out more about me here.

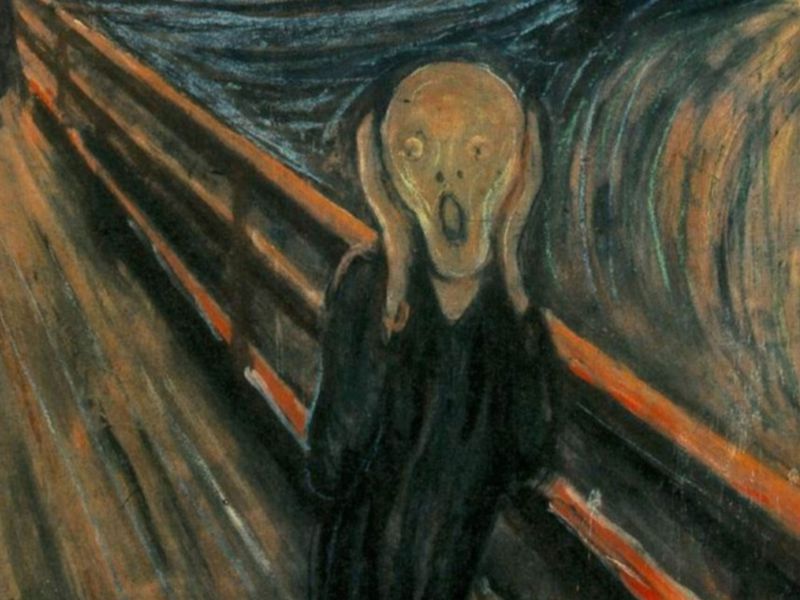

Image: Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893