This is the sort of book writers might write for other writers.

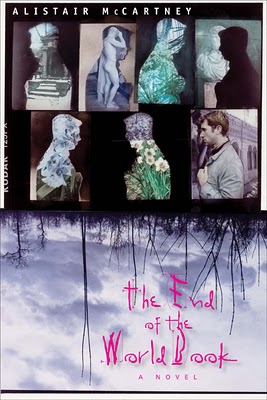

The End of the World Book: A Novel is structured like an encyclopedia, with entries ranging from A to Z. Or, from A to Zed, as the gay writer Alistair McCartney might have said during his childhood in Australia. The premise is that the young Alistair fell asleep one day while reading an encyclopedia, and never woke up. Perhaps the novel is a result of the dream-like state he’s permanently entered into, mixing up past, present and future and conflating truth with fiction. We learn about assholes and the delicate smell that emanates from them as one finger-fucks someone. Avon ladies may be extinct. McCartney states decisively that “the last Avon lady was seen in 1994.”

Presumably, one can dip into the book, as one would into a traditional encyclopedia, or read it from start to finish. I did both, and neither provided a satisfactory experience. AIDS shows up frequently, and it makes for the only somewhat interesting but not entirely compelling aspect of this project. McCartney writes of the “so-called golden era of gay life” which is supposed to have ended with the first case of AIDS in 1981. But, according to McCartney, “the golden era actually begins in 1981 and … stretches backwards like a long gold streak, far away from us … all the way back to antiquity.” With this in mind, he returns to times past and inserts AIDS into the history books, as in his entry on John Keats, “a young porn star…who died of AIDS-related complications in a little room in Rome.” McCartney was born in 1971, and AIDS, for gay men of his generation, can now be divided into an era before and after the 1980s. Which raises the questions: what does it mean to live in an age when one only knows a post-AIDS world? Has it become a presence that overshadows the history of the world?

This is the sort of book writers might write for other writers; its sense of inventiveness overtakes the need to make or reach a point. It’s self-consciously fey and precious, and the narrator’s laconism and self-obsession begin to grate quite early on, even though McCartney’s wit shines through on occasion. As in this entry about the eighteenth-century German poet Jakob Lenz: “Although Lenz didn’t die until 1792 … an obituary for him came out in 1780. For the last twelve years of his life he lived on posthumously.” There’s a matter-of-fact sense of the macabre in everyday life that resembles that of Edward Gorey, evident in an entry about his librarians who “wear thick, horn-rimmed spectacles and walk around, cutting out the tongues of any patron found talking.” But these are bits and pieces here and there, and it’s difficult to plough through the entries without yearning for an end to them.

This is an inventive and experimental book, and a clever book. But it’s not a compelling book. There are interesting characters and subplots, but none are allowed to develop over and above the narrator’s presence. There’s an entry titled “Stories, Absence of,” under which McCartney writes, “take me seriously when I say I have no stories. I couldn’t tell a story to tell my life…” In a book that mixes fiction and fact, that may be the truest statement of all.