“A generation has grown up absorbing Richard’s art, and I have to believe that every one of them is a smarter, funnier, stronger, sillier, more generous person because of him.”

The Muppets have entranced and educated generations of children and generated nostalgic memories for millions of adults. Fans can even take a Facebook quiz to determine which Muppet they most resemble. Yet, comparatively little is known about those who turned the simplest hand puppets into expressive, unique and sometimes cantankerous but always beloved characters. On Jan. 10, the New York City-based writer and zinester Jessica Max Stein will be at Quimby’s Bookshop to discuss the life and work of Richard Hunt, a gay man who was the voice behind Scooter, Janice, Beaker, Statler, Wayne and Sweetums, among many others. He also shared the role of Miss Piggy with Frank Oz until the end of the first season of The Muppet Show.

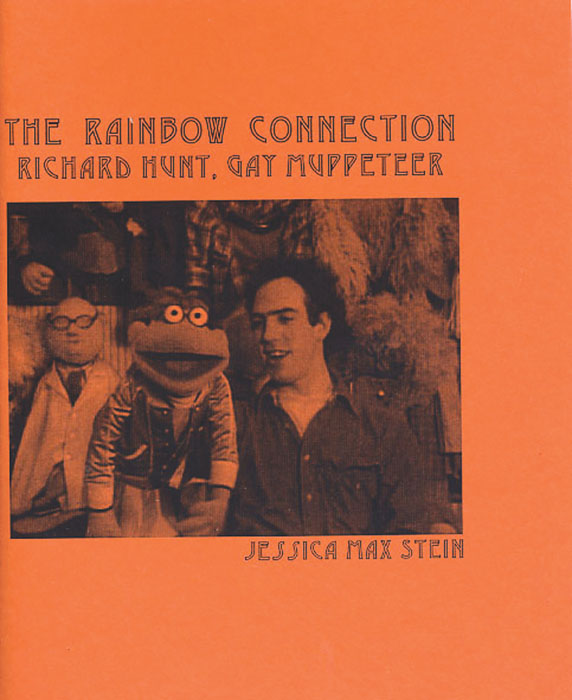

Hunt is the subject of Stein’s new 84-page zine, The Rainbow Connection: Richard Hunt, Gay Muppeteer, which showcases Stein’s interest and absorption in the life of a man who was among the most long-standing behind-the-scenes performers on Sesame Street and The Muppet Show, and whose off-screen humor and colorful personality imbued his puppets with the kind of vivacity that has made them popular for so long. Hunt was born in New York City in 1951 and, according to his mother, got the job on the Muppet Show when, a few months after graduating from high school, he decided to cold call Henson Associates (the late Jim Henson’s company) and ask if they were hiring puppeteers. It so happened that they were auditioning, and Hunt was soon hired.

For Stein, it’s that kind of impetuosity and bravado that proved most intriguing and enchanting as she began to hear more about Hunt’s life and career. Hunt, an out gay man, would go on to become a main performer on The Muppet Show, and one of five performers to be a regular performer on all five seasons. He was also on Fraggle Rock, playing both Junior Gorg and Gunge.

Both Sesame Street and The Muppet Show have gained enormous success and international renown, and those who worked on them have continued to do well professionally in large part, according to Stein, because Henson was intelligent about maintaining creative and financial integrity. Hunt, according to Stein and other historians of the show like Christopher Finch, who wrote Of Muppets and Men, was well-liked, energetic and every bit as playful as the puppets he gave voice to. He died in 1992 of AIDS-related complications, with Frank Oz among those at his bedside. According to the Wikipedia entry under his name, “many panels were created in his honor for the NAMES Project AIDS Quilt, including one created by his friends in The Muppet Workshop.” Jon Stone, a former director of Sesame Street, said about Hunt’s death and influence: “A generation has grown up absorbing Richard’s art, and I have to believe that every one of them is a smarter, funnier, stronger, sillier, more generous person because of him.”

Stein said that her fascination with the man has a lot to do with the ways in which his life and personality imbue the show with a queerness that might otherwise be overlooked if we only think of the Muppets and their characters as aimed at children: “I love that this project speaks to these contradictions,” she told Windy City Times. “People think of muppets as exclusively for kids, but I also see them as very adult and queer. Richard and Oz created Miss Piggy and when you think of it, hers is a total performance of femininity.” What also intrigued her was the character of a man who had clearly engendered fondness, even as some admitted he could be acerbic: “He was totally effervescent; his mom described him as “expansive,” and I see that as a great synonym for ‘big queer.’” Stein was also intrigued by Hunt’s life and work as emblematic of the era he lived and died in: “We can’t separate his life from the times.”

Hunt was in one sense a casualty of the AIDS epidemic, which decimated the U.S. gay male population in particular in the 1980s. But in his death, Stein saw an opportunity to celebrate a decade that the gay community now looks at mostly through the lens of loss and sometimes in very simplified terms, without much attention to the vitality of those who died. Stein is clear that she has no inclination to romanticize the era, and she has friends who speak of feeling like survivors as most of their friends died: “It was a plague.” For her, however, the lingering questions are about how we choose to remember the decade and grieve the dead. The project has also prompted questions about the state of the current gay movement. Speaking of the current emphasis on gay marriage, she said that “We made all these trade-offs and we’ve forgotten that there used to be different options for gay people. People are forgetting that very fast. What I loved about Richard Hunt is that he lived with abundance.” She bases her understanding of him not only through histories like Finch’s book, but also through the interviews she has conducted with the people who knew him, like his mother and co-workers.

The Rainbow Connection was conceived as a zine, but Stein’s research on Hunt has continued even after its publication. She is contemplating the possibility that the greater amounts of material she has since been uncovering might result in a book-length project. For now, she is busy with a zine tour that began in Albany, N.Y. Jan. 2 and will culminate in Chicago. This tour is a follow-up to the first one she undertook in the summer of 2009, traversing New York City; Madison, Wis.; Minneapolis, Minn.; Portland, Ore.; and San Francisco. Stein is especially looking forward to connecting with the motley crew of people that comprise her audiences: “the readings bring together a lot of people who wouldn’t otherwise be in the same room: the fanboy nerdy straight guys, the people who just love the Muppets, queers.”

Originally published in Windy City Times, 6 January, 2010.